Şapeltoun - Chapeltoun

Şapeltoun Annick Water kıyılarında bir mülk East Ayrshire, İskoçya. Burası sütü ile ünlü kırsal bir bölgedir ve peynir üretim ve Ayrshire veya Dunlop sığır ırkı.

Templeton ve Tapınak Şövalyeleri

feodal Hugh de Morville gibi derebeyinin vasallarına kira tahsisi çok dikkatli bir şekilde gerçekleştirildi, sınırlar yüründü ve dikkatlice kaydedildi.[1] Bu sırada 'ton' terimi, bir duvar veya çitle sınırlanmış büyük bir taştan yapılmış yapı olması gerekmeksizin, konutun bulunduğu yere eklenmiştir. Kiralamalar askeri bir görevde yapıldı ve arazi, efendiye askeri yardım karşılığında verildi. Daha sonraki yıllarda askeri yardım, mali ödeme ile değiştirilebilir.

Templeton adı, buradaki toprakların derebeyi tarafından bir vasala verilmesi nedeniyle ortaya çıkmış olabilir. Orijinal konutun yeri bilinmemektedir, Laigh Chapelton, muhtemelen en az 1775'ten kalma bir yerleşim yerinin bilinen en eski alanıdır.[2]

Chapelton adı nispeten yenidir. Pont's Haritası 1604 böyle bir yer adı göstermez; ancak, Annick Water ve Glazert Water arasında yaklaşık olarak doğru yerde bir Templeton gösteriyor. Diğer tapınak Şövalyeleri tapınak arazileri, yakınlardaki eski Darlington köyündeki Templehouse ve Fortalice'de bulunacaktı. Stewarton, Templehouse yakınında Dunlop, Crookedholm'un eteklerindeki Templetounburn'de ve Temple-Ryburn ve Temple-Hapland gibi bölgedeki diğer birkaç yerde.

1312'de İskoç karargahı şu anda bulunan Tapınak Şövalyeleri tarikatı Torphichen, dağıldı[3] ve toprakları Aziz John Şövalyeleri[4] bugün kim koşuyor St John Ambulans diğer faaliyetler arasında. Lord Torphichen hoca olarak tapınak arazisini aldı ve topraklar, aristokrasinin elinden geçmeden önce, 1720'de Hessilhead'in Montgomerie'sinin elinden Cairnhill Wallace'a (şimdiki adı Carnell) geçti. Kira, üzerinde bir bina bulunan ve kiracı tarafından kullanım hakkına sahip olan bir arazi hibesidir.[5]

Bölgedeki çiftlikler 1829'da (Aitken) Chapelton adını kullandı ve Armstrong'un 1775 haritası bir Şapeli gösteriyor ve adlandırıyor. Templetoun'dan Chapelton'a isim değişikliği, 1720'den bir süre sonra tapınak topraklarının resmi varlığının sona ermesinden veya bu toprakların mülkiyetinin bu tarihte veya muhtemelen biraz daha erken bir tarihte dağılmasının bir sonucu olarak ortaya çıkmış olabilir. Böylece 1604'te Templeton adı kullanılıyordu.[6] 1654'te, ancak 1775'te değil[2] 1665 tarihli Katherine Muir / Mure'nin Stewarton Parish'inde Chapeltoun'lu William Hepburn kalıntısının vasiyeti,[7] daha erken bir tarihte isim değişikliği anlamına gelir. Bu Chapeltoun, günümüzün Chapeltoun Mains'ı olabilir.

Paterson (1866)[8] şunu belirtir Langshaw topraklarında (şimdiki Lainshaw) bir şapel vardı. Meryemana ve uygun bir donanıma sahip olduğunu. Sonra Reformasyon bağış, patron tarafından tahsis edildi ve şapelin harabeye dönmesine izin verildi. Tapınak arazileri yerel kiliseyi korumak için para vermiyordu ve bu nedenle çok değerli ve kazançlı bir varlıktı.

1616'da şapelin ve Peacock Bank (sic) topraklarının himayesi, Eglinton Kontu tarafından verilen 'clare constat' olarak Lainshaw'dan Sir Neil Montgomerie tarafından yapıldı, ancak 1661'de himaye bir kez daha doğrudan Kontu tarafından yapıldı. Eglinton aşağıda belirtildiği gibi. Şapelin bulunduğu yer 17. yüzyılda Chapelton ve 1874'te Chapel olarak adlandırılmıştır. Aynı bilgi Paterson tarafından verilmektedir.[8] 1866'da, 1885'te Groome ve Barclay'de.

| Etimoloji |

| İsim Şapeltoun açıkça ortaya çıkıyor Şapel ve TounKilmaurs-Glencairn ve Stewarton kirk'lerinde olduğu gibi, şapel çevresinde küçük bir yerleşim yeri bulunduğunu gösterir. |

Dobie[4] 1876'da, Hugh, Eglinton Kontu, Mayıs 1661'de, bu topraklarda Kutsal Bakire Şapeli'nin himayesinde Langshaw'ın 10 merklandını miras aldığını kaydeder. Ailesi birkaç nesil boyunca bu toprakları elinde tutan James Wyllie'ye atıfta bulunulur. Bu açıklama, çoğu Dunlop malikanesine ait olan daha büyük bir arazinin parçası olan Gallaberry'nin 5 merk topraklarına yapılan atıfların bir parçası olarak yapılmıştır. Gallaberry adı[4] Saxon kelimesinden türediği düşünülmektedir burgh ve Kelt kelimesi Galyalılar, bu nedenle terim Galyalıların kenti, konağı veya gücü anlamına gelir. Sanderson, Lainshaw topraklarında bulunan Meryem Ana'ya adanmış kırsal bir şapelden bahseder.

Dobie'nin 1640 Kilmaurs değerleme rolünde Tempiltoun adında üç aileyi listelediğini ve diğer hiçbirunninghame cemaatinin bu adın listelenmediğini belirtmek önemlidir. Kilmaurs-Glencairn kilisesinin 17. yüzyıldan kalma en eski mezarlarından biri Tempiltoun'a aittir. Templetons ailesinin İncil'i (2008), doğrudan soyundan gelen Byres Çiftliği Ormanları tarafından tutulur.

Şapel ve Şapel Tepesi / Mezar Höyüğü / Moot Tepesi

Dobie, iki şapelin bulunduğunu belirtir. Lainshaw ve Chapeltoun'da biri, ancak 'ekli' terimini karıştırmış olabilir; bu, kaleye yakın olmaktan ziyade, sahibi veya Baron Lordu'nun topraklarında olduğu veya bahşedildiği anlamına gelebilir. Lainshaw'ın evi. Paterson'ın sadece bir şapelin var olduğunu ve onun Chapelton'da olduğunu ima eden açıklaması doğruysa ve kendisi yerel olarak yetiştirilmişse, o zaman Aziz Mary Şapeli'nin tarihi hakkındaki bilgimiz büyük ölçüde artar.

1846'daki İskoçya Topografik Sözlüğü, "Chapelton çiftliğinde (şimdi Chapeltoun Mains) kasabadan (Stewarton) yaklaşık bir mil uzakta, yakın zamanda eski bir şapelin temellerini kazdığını, ancak hiçbir otantik kaydın bulunmadığını belirtir. korundu. "

Ocak 1678'de, Edinburgh'da eczacı / eczacı / cerrah olan Robert Cunynghame, Auchenharvie'den Sir Robert Cunynghame'nin kızı Anne'nin varisi olduğu belirtildi. O onun kuzen-alman ve mirasın bir kısmı, şapel toprakları ve Fairlie-Crivoch'un parıltısı ile Fairlie-Crivoch'un 10 merk ülkesiydi. Bölgede başka hiçbir şapel yoktur, bu nedenle bu büyük olasılıkla Chapelton'daki Chapel'e atıfta bulunmaktadır. Ayrıca topraklarının çoğuna da sahipti. Lambroughton. Crivoch bir baronyti ve topraklar Lindsay-Crevoch ve Montgomerie-Crevoch olarak ikiye ayrılmıştı. Fairlie Crevoch, muhtemelen Kennox'taki eski Crivoch Değirmenine yakın bir mülktür.

Şapel asla çok büyük olamaz ve eski Roma Katolik rahibinin önderliğinde İskoçya'daki Protestan reformu sırasında terk edilmiştir. John Knox (1514 ila 1572). 1775 Armstrong haritasında bir harabe olarak değil, küçük bir konak olarak işaretlenmiş olup, 1775 Laigh'e (muhtemelen daha sonra Chapelton olarak adlandırılır) ek olarak, civarda bir Şapel Evi'nin var olduğunu ima eder. Bu sitenin şu anda sadece 'şapel' olarak adlandırıldığı ve Armstrong'un haritasında verilen adın bu olduğu belirtildi.

Rahibin konutunun bulunduğu yere dair hiçbir kanıt yoktur, ancak eski Templeton / Chapelton House'un yeri kendisini göstermektedir. 1775 haritasında gösterilen Laigh, Laigh Chapelton'a atıfta bulunursa, şapelin çevresindeki tek başka isimlendirilmiş site olduğu için sitenin antikliği daha da geliştirilir.

Manastır yerleşiminin tarihi ve kilisenin yanındaki Şapel Kayalıkları'ndaki Aziz Meryem Şapeli Thugart stane / T'Ogra Stane / Thurgatstane / Thorgatstane / Field Spirit Stane / Ogrestane yakın Dunlop Chapel Hill'deki Chapel'e paralel bir örnektir. Pagan taşı hala varlığını sürdürüyor, 13 fit (4.0 m) uzunluğunda, 10 fit (3.0 m) genişliğinde ve 4 fit (1.2 m) yüksekliğinde,[9] ancak yanıkla çevrili alanda göze çarpmayan Kutsal Kuyu dışında Hristiyan yerleşim yerlerine dair hiçbir kanıt görünmüyor. Bayne, taşın bir sallanan veya 'logan taşı' bir keresinde ve muhtemelen kökeninde 'buzul düzensizliği' olan bu anıtın etrafındaki pagan mezarları geleneği nedeniyle, çiftçinin taşa belirli bir mesafede sürmesine izin verilmediği kaydedildi. Hala tapınıyordu "papalık zamanları"McIntosh'a göre.

Bölgenin topografyası, erken dini kurumlar için seçilen türden tipik bir sitedir ve pagan sitelerinde şapel veya kiliselerin inşa edilmesi, Hıristiyanlığın pagan inançları ve uygulamalarının yerini almasının klasik bir örneğidir. Her iki dini mekan da bol akan su ile korunaklı vadilerdedir ve görüş alanından gizlenmiştir.

1775 Armstrong'un belirtildiği gibi[2] Ayrshire haritası açıkça işaretlenmiş bir 'Şapel'i gösteriyor, bu yüzden şu anda var olduğu biliniyordu, ancak kalıntılar yıllar içinde yerel çiftçiler tarafından çıkarılmış / kaldırılmış ve inşaat işleri için kullanılmış olabilir, vb. Şapelin kalıntıları. 18. yüzyılın başlarında bulunması zor olmuştur. Okçu[10]1807'nin haritası Linshaw (Lainshaw) yakınlarında işaretlenmiş ve Laigh'den bahsedilmeyen Şapeli gösterirken, Ainslie'nin 1821 haritasında bir Şapel ve Laigh gösteriliyor.[11] Çoğu haritalardaki Şapel terimi, höyükteki Şapeli değil, bir konut veya çiftliğe atıfta bulunuyor olabilir.

1856 'İsim Kitabı'[12] of işletim sistemi Chapelton evinin bir kısmının (NS 395 441), kiliseye adanmış bir şapel olduğuna inanılıyor. Meryemana. Binanın bazı bölümleri çok eski olmasına rağmen, buranın şapel olduğu kesin değil; Şapel, Chapel Hill yakınlarında dururken, papazın ikametgahı olabilir. Bu Chapel Hill dairesel bir yapay tepedir. Yaklaşık 1850 yılında, Bay J McAlister, yanlarından kayan toprağı vb. Alıp üstüne koyarak onu bugünkü yüksekliğine yükseltti. Bunu yaparken, S ve E taraflarında üssün yakınında bir miktar insan kemiği ve ayrıca Bay McAlister'ın eski şapelin ateşle tahrip edildiğini düşündüren görünüşlerinden ateşe maruz kaldığını düşündüğü bazı taşlar bulundu. Eski mülk sahibi Bay R Miller, Chapel Hill'den geçen mevcut yol yapılırken, burada bir mezarlık olduğu fikrini veren bir miktar kemik bulunduğunu belirtti.[12]

Smith,[9] iyi bilinen antikacı, 1895'te höyüğün 22 adım çapında, alçakta 20 fit (6,1 m) yükseklikte ve yüksek tarafta 7 fit (2,1 m) yükseklikte olduğunu tanımlamaktadır. İyi bakıldığını ve bugün açıkça görülemeyen bir basamak uçuşunun tabanından tepeye doğru koştuğunu belirtiyor. Bununla birlikte, şapelin kendisinin herhangi bir kalıntısına atıfta bulunmaz. 1897 25 "mil OS, höyüğün Chapelhill House tarafında bir patika ve muhtemelen kıvrımlı bir yol veya basamakları gösterir. Smith ayrıca höyüğün yaklaşık elli yıl önce onarıldığını ve bunun yaklaşık tarihlere uyduğunu belirtir. James McAlister tarafından veya onun için Chapelton (eski) evin olası inşaatı[4] Bu sıralarda Chapelton'un sahibi olarak verilen ve 1874'te şapel kalıntılarının 40 yıl kadar önce yani 1834 civarında bulunduğu belirtilmektedir. 1846 kaydı, yakın zamanda bulunduklarını belirtir (Topo Dict Scot) .

1842'de[13] kaydedildi "Low Chapelton çiftlik evinin yakınında, Stewarton'un bir mil yukarısında, Annock'un sağ kıyısında, bir zamanlar bir şapel varmış gibi görünüyor; bu şapel, mülk sahibi ağaç dikmekle meşgulken son zamanlarda kalıntıları kazılmıştı. İbadet yerine dair hiçbir kayıt kalmamıştır."

Fullarton bunu kaydeder ".. ismini burada bulunan ve duvarlarının bazı parçaları hala bu iffetli ve zarif kır evi ile bağlantılı olan eski bir şapelden almıştır. Saha, nehrin kenarına yakın, ince korunaklı bir çöküntü içinde, tuhaf bir manastıra ait."[14]

1980'lerde bir grup 'Wicca "Chapel Hill tepesini seçti"Cadılar bayramı 'büyük bir şenlik ateşi vb. ile festival, yerel halkı şaşırtacak şekilde.

Chapelton Moot

Bir Chapelton Moot Tepesi 15. yüzyılda Alexander Hume'a Lainshaw, Robertland ve Gallowberry gibi arazilerin hibe edilmesinden Kral James tarafından özel olarak çıkarıldığı İskoçya Büyük Mührü Kaydı'na kaydedilmiştir. Bu, bir mezar höyüğünün ikincil bir kullanımı olabilir, ancak bir dizi 'Moot' veya 'Justice' Tepesi bu amaçla inşa edilmiş gibi görünüyor. 15. yüzyıl tarihinin reform öncesi olduğu ve bu nedenle şapelin hala kullanımda olacağı düşünüldüğünde, şapelin kendisinin tepede olmadığı anlamına gelebilir.

Chapel Hill için alternatif isimler

Mezar höyüğü için alternatif yerel isimler 'Jokey şapkası' ve 'Keşişin Mezarlığı'dır, 1897 OS haritası tepede insan kemiklerinin bulunduğunu belirtir. Byres Farm'ın Forrest ailesi, Templetons'un doğrudan torunlarıdır ve Chapel Hill için 'Monk's Graveyard' terimini kullanırlar. Bu durumda sözlü geleneğin geçerliliği son derece güçlüdür ve şapelin höyüğün üzerinde değil, eski Chapelton Evi'nin yerinde olduğunu gösterebilir. John Dobie, babasının çalışmalarına ek notlarında siteyi 'Chapeltons' olarak adlandırıyor. Höyüğün kendisi, Ayrshire'daki en iyi korunmuş Tunç Çağı mezar höyüklerinden biridir.[9] Chapel Hill höyüğünün önceki bir sahibi, 2001 yılı civarında resmi olmayan bir kazı yapılmasına izin verdi. Herhangi bir buluntu bulunup bulunmadığı bilinmemektedir.

Tarafından bir ziyaret işletim sistemi Ağustos 1982'de, "Bu özelliğin doğru bir şekilde değerlendirilmesinin zor olduğunu belirtmiştir. Açıkçası, orijinal halinin hiçbir şekilde tanınamayacak şekilde değiştirilmiş ve peyzajı yapılmıştır ve şu anki haliyle süslü bir görünüme sahiptir. Yaklaşık 60 metrede K-G eğimli çizgi, bunun bir zamanlar sadece hafifçe yükseltilmiş bir burun olması mümkündür, ancak bu nedenle, neredeyse kesinlikle bir hareket değildir ve bu bölgedeki bir çiftlik evi konumu için daha tipik olacaktır. "

'Jokey Şapkası' adı, yıllık 'Stewarton Bonnet Guild Festivali' at yarışı dahil - tıpkı Irvine Marymass Kutlamalar hala devam ediyor. Höyük, Chapeltoun Mains'ın altındaki alanda kurulan 'hipodromu' izlemek için mükemmel bir yerdi. Höyüğün şekli bir jokey şapkasını andırıyor.

Chapelton ve Kennox bağlantısı

Lainshaw'dan Sir Neil Montgomery, Aiket'ten Elizabethscapehame ile evlendi ve oğullarından biri olan John of Cockilbie'nin 17. yüzyılın ortalarında John of Crivoch adında bir oğlu oldu. Somervililer tarafından satın alınmadan önce Crivoch'ta yaşamış ve evlenerek MacAlisters'a geçmiş olabilir.[8]

Auchenharvie'den Sir David Cunningham'ın kuzeni Robertland'ın İskoçya Ulusal Arşivleri'nde saklanan mektupları, bu toprakların bir kısmını satın alma çabalarını detaylandırıyor (NAS GD237 / 25 / 1-4) Bazılarını James'e sattı. 1642'de Douglas of Chesters (RGS, ix, (1634–1651), no. 1189) Lanarkshire'daki Kennox Estate'ten John Somerville, Chapeltoun da dahil olmak üzere Bollingshaw (şimdi Bonshaw) Barony'yi satın aldı ve Kennox'u (ayrıca Kenox 1832 ve Kennoch, 1792) Montgomerie - Crevoch topraklarındaki ev.[8]

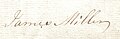

1775'te daha sonra Laigh Chapelton olarak adlandırılan Chapelton'u miras alan James Miller'ın imzası.

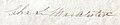

1789'da Chapelton'u miras alan ve daha sonra Laigh Chapelton olarak adlandırılan John Miller'ın imzası, 1789'da babası James'ten.

Albay Charles Somerville McAlester Esq'in imzası. 6 Şubat 1827'de Chapelton'u satın alan.

James Somerville McAlester Esq'in imzası. Laigh Chapelton'u 25 Nisan 1848'de babası Charles'tan devralan Kennox'un

Chapelton malikanesini James McAlester Esq'ten satın alan Barrhead Demir Ustası John Cunningham'ın imzası. Mayıs 1874'te.

Monkcastle'dan John Archibald Brownlie'nin imzası Chapelton malikanesini 21 Kasım 1888'de John Cunningham, Ironmaster, Barrhead'den satın aldı.

1728'de Mosshead'de yaşayan John Faulds'un imzası.

1848 İmza parşömen William Cuninghame Esq. Lainshaw'dan, Lainshaw Baronyasından daha üstün.

İlk'den Hugh Montfode kız kardeşi Jean, 1622'de ölen Laigh Chapelton'dan John Miller ile evlendi; bir oğulları Hugh Miller vardı. Jean Montfode, John Miller'ı vasisi olarak aday gösterdi.[15] Amerikalı soybilimci Steve Miller, 1828'de merhum John Miller'ın, o zamanlar burada yaşayan oğlu James aracılığıyla olduğunu ortaya çıkardı. Montfode Evi, Kennox'tan Albay Charles S. McAlister tarafından dava açıldı.[16]

Charles S. McAlister ve Janet'in dört çocuğu vardı. Bollingshaw Barony'sinin Chapelton adlı bölümünü (Sasines Sicilinin glebes ve şapel toprakları) 1857'de hiç evlenmeyen ve ölmeyen küçük oğulları James'e miras bıraktılar.

James Somerville'in Chapelton'ı ne zaman alacağına dair bir tarih verilmez, ancak Dobie'den, yukarıda adı geçen James'in yeğeni James McAlister'ın 1874'te sahibi olduğunu biliyoruz. James Somerville'in yeğeni olan James McAlister da hiç evlenmedi. Chapelton, babası Charles McAlister tarafından Bollingshaw Barony'sine yeniden satın alınmıştı.[8]

Templeton, Chapelton olur ve bir Malikaneye dönüşür

1775 tarihli Armstrong haritası, 'Şapel'e oldukça yakın bir' Laigh 'gösteriyor. Bu, büyük olasılıkla Laigh Chapelton, bu tarihte bir konutun var olduğunu öne sürüyor ve Laigh Chapelton'un bazı önemli antik çağlardan kalma bir bina veya bir binanın alanı olduğu varsayımına güç katıyor. 1820'de 'Laigh Chapelton'dan John Miller tarafından açılan' High Chapelton'dan James Wilson için Savunmalar 'adlı yasal bir belge, bize bu mülklerin her ikisinin de şu anda kiracılarının isimlerini veriyor.[17] 1820 dolaylarında kira değeri 180 sterlin idi.[18]

Templeton'dan Chapelton'a resmi isim değişikliği, St. Mary's Chapel harabelerinin yeni toprak sahibi James McAlister tarafından yeniden keşfedilmesinin bir sonucu olarak gerçekleşmedi, çünkü açıkça hiç bu şekilde kaybolmamıştı. Ancak keşif, Laigh Chapelton'daki evin yeniden inşası / genişletilmesi için yaklaşık bir tarih sağlamaya yardımcı olabilir. Paterson, 1866'da şapel keşfinin birkaç yıl önce olduğunu, Dobie'nin kanıtlarının bize 1836 tarihini ve Smith'in kanıtının 1845 tarihini verdiğini söylüyor. Aitken, 1829'da yalnızca bir Laigh Chapelton Çiftliği gösteriyor ve tüm bunlar 'eski' Chapelton Ev ve mülkler 1830-1850 yılları arasında geliştirildi. 19. yüzyılın başlarından ortalarına kadar birçok kır evinin inşa edildiği, modernize edildiği veya genişletildiği bir dönemdir.[19] ve işletim sistemi haritaları, resmi bahçelerin (1858 İşletim Sisteminden itibaren), yeni araba yollarının vb. geliştirilmesi ile bu dönemde Laigh Chapelton arazisinin artan önemini göstermektedir.

Şapeltoun Şebekesi

Chapeltoun (Chapleton, Chappleton, Chapeltown, vb.) Mains çiftliği, adını Laigh Chapelton'un 1829 ile 1858 yılları arasında yeni malikanenin yeri olarak benimsediği basit Chapelton'dan değiştirmiştir. Bu, şu anda Chapelton Mains'in OS haritalarından değerlendirildiği gibi, 1911'de şu anda Chapelhill House'un inşa edilmesinden önceki ev çiftliği. 1858'den kalma Chapelburn Kır Evi'nin yakınında küçük bir bina belirir. Çiftliğin ön tarafındaki alana 'Black Sawneys Parkı' denir; 'Sawney 'İskender' için İngilizce bir terim olmak. Bir zamanlar, 'Jock' adının kullanımında olduğu gibi, bir 'İskoçyalı' anlamına geliyordu. Diğer bir açıklama ise, nehrin holm üzerine taşması ve zengin verimli topraklar oluşturması nedeniyle tarlanın siyah kumlu toprağa sahip olmasıdır.[20]

Watthode

Wattshode veya Wattshod olarak adlandırılan Chapelton'un 5 Merk arazisinde 4 dönümlük (1.6 hektar) küçük bir mülk, Chapeltoun Mains yasal belgelerinde 1723 yılına kadar belirtilmiştir.[21] Armstrong, 1775'te bir 'Wetshode' kaydeder.[2] 1598'de 'Wattshode' kelimesi, genellikle mavi olarak tanımlanan bir tür kumaştı. Yerel soyadı 'Watt' içerebilir.

Bogflat'a giden yolun yanında bir sığınak kemeri ve ısırgan otu bir binanın olası alanıyla sınırlı büyüme, Wattshode'un Cankerton'un (daha önce Cantkertonhole) arkasındaki bu 4 dönümlük (1,6 hektar) alanda durduğunu gösteriyor.[21]). General Roy'un 1747-55 haritası sadece Watshode ve Chapeltoun'u ismen işaret ediyor. 'Red Wat-shod', Robert Burns tarafından kullanılan kan sıçrayan botlar anlamına gelen bir İskoç ifadesidir.[22]

Chapelton Moss Head, Bottoms noktası Crivoch ve Bogside

Başlangıçta Thomson tarafından 1828'de Chapelton Moss Head veya Chapelton'dan Mosshead olarak adlandırılan bir çiftlik daha sonra sadece Mosshead olarak adlandırılır ve Chapel Burn üzerindeki köprünün hemen arkasındaki girişi ile Bottoms Farm'ın tarlalarında yer alır. Bogside kır evi, Bogflat Çiftliği'nin girişine yakın tarlanın kenarındaki enkazla temsil edilirken, yerin üzerindeki tüm izleri kayboldu. Bogside'ın 1820'de kira değeri 10 £ idi ve sahibi Robert Stevenson'du. Dip notu Crevoch çiftliği hala Kennox'a (2009) yakın bir yerde bulunmaktadır.

Bogflat

Bogflat Çiftliği, 2004 dolaylarında Stuart Kerr ve eşi Stephanie tarafından sevgiyle yeniden inşa edildi. Stewarton Old Parish Records, Hugh Parker ve eşi Susanna Wardrop'un kızları Annabella doğduğunda 1809'da Bogflat'ta yaşadığını gösteriyor. Parker'lar 1841 nüfus sayımı sırasında hâlâ ikamet ediyorlardı. Komşular, Bogflat Çiftliği'nden Susanna Wardrop Parker ve Parkside Çiftliği'nden Agnes Wardrop Watt kardeşti. John Earl ve eşi Isobel, 1827'de Bogside'da ikamet ediyorlardı.[23]

1881'de 38 yaşındaki bir tüccar olan Alexander Muir, karısı Margaret ve oğulları David ve John ile birlikte Bogflat'ta yaşıyordu. Bog adındaki bir bina Armstrong'un 1775 haritasında işaretlenmiştir ve bu büyük bir olasılıkla Bogflat'tır. Evlilik taşı Bogflat'tan, şimdi Stewarton Müzesi'nde, 1711'de bir 'JR' kaydedilmiş bir konut vardı ve maalesef şimdi diğer baş harfleri kesildi.[24]

1919'da Avustralya'nın Melbourne İthalat ve İhracat Tüccarı Robert Bryce, Chapelton ve Bogflat'a sahipti.[25]

Parkside (Windwaird) ve Cankerton Hollow

Windwaird, 1829'da Torranyard'da Stewarton yoluna giden bir eve Aitken tarafından verilen addır, Anderson Plantation'dan geçen Lainshaw Evi'ne yayalar için oldukça yeni oluşturulan girişten çok da uzak değildir (haritalarda işaretlenmiş ancak harita tarafından kullanılmayan bir isim) yerel çiftçiler). Bu bina, ilk olarak 1832 haritasında gösterilen OS haritalarında Parkside olarak adlandırılır, 1960'ta işaretlenmiştir, ancak 1974 OS'de işaretlenmemiştir. Stewarton Old Parish Records, Alexander Watt ve karısı Agnes'i (Wardrop), kızları Mary'nin Mayıs 1809'da doğduğu zaman Parkside'da gösteriyor. 1809'da, Bogflat Çiftliği'ndeki komşuları Susanna Wardrop Parker ve Parkside Çiftliği'ndeki Agnes Wardrop Watt kız kardeşlerdi. Burada yaşayan son aile, Muir's of Gillmill (ayrıca Gillmiln) Çiftliği'nin akrabaları olan Muir'lerdi. Bir 'park', çoğu arazinin çitlerle veya çitlerle çevrilmediği günlerde kapalı bir arazi alanını ifade eder.

1616'da "Waird toprakları vb." William, Lord Kilmaurs (McNaught 1912) tarafından Robertland'den Davidunninghame'e aktarılmıştır, ancak bu siteyle herhangi bir bağlantısı kanıtlanmamıştır. Bir Waird kiracıların askerlik hizmeti yükümlülükleri ile tanınan feodal bir arazi kullanım hakkıdır (bkz. Tanımlar ve Scot'ın sözleri). Lochridge yakınlarındaki Wardpark, Pont'un 1604 tarihli haritasında Wairdpark olarak yazılmıştır.

Cankerton veya Cankerton Hollow nadiren adıyla belirtilir; 6 Nisan 1859'da 43 yaşında (31 Mayıs 1845 doğumlu) ölen çiftçi James Orr'un eviydi. Karısı Mary King Brown, 12 Temmuz 1845'te henüz 25 yaşında öldü (20 Eylül 1820 doğumlu).[26] Başka bir John Orr, eşi Janet Wilson ile burada çiftçilik yaptı. 21 Ocak 1847'de 68 yaşında öldü ve 16 Ekim 1889'da 79 yaşında kardeşleriyle birlikte yaşamak için High Chapeltoun'a taşınarak öldü. Kocası ve eşi, Stewarton'daki Laigh Kirk'e gömüldü. Cankerton, aslen Cankerton yerel olarak bir soyadı olarak da bulundu, ancak etimolojisi belirsizdir, genellikle ağaçların veya tahılların 'yanıklığı, mantar hastalığı' anlamına gelen bir 'pamukçuk'. Bir Cankerton Estate, kömür yatakları araştırması altında listelenmiştir.[27]

Chapelton ve Stacklawhill'den Mary Reid'in mezar taşı.

Yıkılan Chapelton House'un eski kapı direkleri, Chapel Hill yakınlarında yatıyor. Arka plandaki kuru taş daykları eski evin taşlarından yapılmıştır.

Archibald Brownlie'nin 1895 tarihli not defteri.

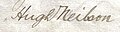

Chapelton'u 1899'da Banker, Monkcastle'dan J Archibald Brownlie'den satın alan Hugh Neilson'ın imzası.

Yüksek Şapeltoun

High Chapelton ilk olarak 1829 ve 1858 haritalarında, Annick üzerinde bir limekiln ve bir ford ile birlikte işaretlenmiştir. Çiftlikten Laigh Castleton yakınlarındaki 'tahıl ambarını' içeren tarlaya giden eski bir yol görülüyor; Bu tarlada çiftçilik yapmak, herhangi bir taş, bina veya başka bir şekilde ahşaptan yapılmış bir bina olduğunu düşündürmedi. James Wilson ve eşi Mary Steven, 1760 yılında, 56 yaşında öldüğünde High Chapeltoun'da çiftçilik yaptılar. Stewarton'daki Laigh Kirk'e gömüldüler. High Chapelton ve Stacklawhill'den Mary Reid, 20 Ocak 1827'de Stacklawhill'den Thomas Reid'in kızı olarak burada doğdu. Karısı, High Chapelton'dan Mary Wilson'dı. Anıt taşı Stewarton mezarlığında. 1820 civarında kira değeri 137 sterlin idi.[18]

Chapelton (eski) evi ve bahçeleri

1858 OS, sahada birbirine çok yakın ancak fiziksel olarak bağlı olmayan iki bina gösterir. Bir bina muhtemelen eski Laigh Chapelton Çiftliği, diğeri ise sağda James McAlister için inşa edilen konuttur. Fotoğraf (Davis 1991), evin yola ve Chapel Hill'e bakan tarafında görünüyor. 1851 İşletim Sistemi, bir sınır duvarı, yolları ve merkezi bir özelliği, muhtemelen bir göleti olan resmi bahçeleri gösterir. 1897 OS, sundurma ve muhtemelen bir kış bahçesi gibi görünen kanatları ve uzantıları olan büyük bir binayı göstermektedir. Bu tarihe kadar, 1911 İşletim Sisteminde olduğu gibi resmi bahçeler yok. ha-ha 1897 OS'nin büyük ölçekli haritasında gösterilmemiştir, ancak 1858 ve 1911 sürümlerinde mevcut olduğu görülmektedir. Yaya köprüsü çıkarılamaz, ancak işletim sistemi haritalarında bir dizi hata ve eksiklik vardır, özellikle de genellikle sadece 'yaklaşık değerler' olan binaların tam ana hatları. 1858 ve 1897 yılları arasında, Chapel Hill'in neredeyse karşısındaki araziye bir ana araba yolu inşa edildi ve bugünün ana girişinden Chapelton House'a kadar uzanan basamaklı resmi bir yol.

Yeni Şapeltoun Evi ve Sitesi İnşaatı

Chapelton (eski) Evi, 1908 civarında, muhtemelen bir yangının ardından yıkıldı, çünkü bu, evin ölümü için güçlü yerel gelenek.[28][29] Bayan Mary McAllister evin son sakini olabilir.[30] Giyinmiş taş işçiliğinin bir kısmı yeni evin inşasında, bahçede ve taşıt duvarlarında, Şapel'in yanıklarında ve başka yerlerde kullanılmış olabilir. Chapel Hill höyüğünün tarla tarafının etrafındaki duvar tamamen Chapelton (eski) Evi'nden gelen taşlarla inşa edilmemiştir, çünkü Chapeltoun Mains'ın sahibi Bay A. Robinson tarafından çok daha sonraki bir tarihte başka bir yerden bazı eski bina molozları getirilmiştir. .[17]

Höyüğün altındaki tarlaya açılan kapı, yatay olarak yerleştirilmiş üç kumtaşı kapı direğine sahiptir, bunlardan ikisi son derece büyüktür ve eski giriş ve araba yolundan Chapelton (eski) Evi'ne kadar olan süslü geçitler olabilir. Gerçek sürücü şimdi duvarla çevrili girişin arkasındaki kıvrımlı havuzla temsil ediliyor ve OS haritaları en az 1911'e kadar burada bir giriş gösteriyor. Chapeltoun Mains'de yalnızca bir kapı kapısı var ve hem High Chapeltoun hem de Chapelhill evinde hiç yok. Bu değişiklikler muhtemelen büyük modern tarım makinelerine erişim gerekliliğini yansıtıyor. Kapı direkleri makine ile kesilmiş kumtaşıdır ve aynı tasarım, Kennox locası, Cankerton ve Lochridge'e giden orijinal giriş yolunun yakınında Stewarton yakınlarındaki Peacockbank Çiftliği (daha önce Pearce Bank) gibi başka yerlerde de bulunur. 1775'te Armstrong'un haritası Lochridge'den (eski adıyla Lochrig) daha ileriye gitmeyen yolu gösteriyor. 1923 OS haritasında Chapeltoun House'un yukarısında bir rüzgar pompası gösterilmektedir.

Yıkım sırasında not edildi[19] Chapelton (eski) House'un alt katındaki taş işçiliğinin, Laigh Chapelton daha büyük mali imkânlara sahip bir sahibi, Bay James McAlister (veya MacAlester) edindiğinde Chapelton'a dönüşmüş olsaydı bekleneceği gibi, üst kattaki taş işçiliğinin fark edilir derecede eski olduğunu, Önce yeni bir 'malikane', daha sonra eski çiftliğe bir üst kat ekleyen, süs bahçelerini geliştiren ve muhtemelen ilişkili 'ha-ha' ile nehir üzerindeki köprüyü inşa eden (arsa bahçeleri ve peyzaj bölümüne bakın) .

Michael Davis, şirketin sahibi Hugh Neilson'ın "Summerlee Demir Şirketi" şimdiki konak evini 1908 yılında Alexander Cullen, [1] Hamilton'dan bir mimar. Harling, duvarlarda yoğun olarak kullanılır ve bu, orijinal olarak boyanmamış, sanatsal, gri bir durumda bırakılmıştır.[31] Aile 1910'da eve taşındı, ancak Cullen, Lochhead ve Brown tarafından tasarlanan kapı köşkü 1918 yılına kadar inşa edilmedi. R.W. Schultz, 1911'de teraslı bir bahçe önermişti, ancak mevcut terasların bu tasarımı ne ölçüde yansıttığı bilinmemektedir. Ana basamakların dibindeki sütunlar, muhtemelen Chapelton (eski) Evi'nden kalma eski dekoratif işlenmiş kumtaşı içerir. Kilmarnock Glenfiled Ramblers'a göre evin önünde bir zamanlar ayrı bir kış bahçesi binası vardı.[32] Ekstra 'u' harfiyle birlikte 'Chapeltoun' adı muhtemelen yeni konak için benimsenmiştir.

Bir zamanlar Oak Bank Foundry'de Bay Neilson tarafından yaptırılan evin önünde 1840 tarihli küçük bir demir top duruyordu.[32]

Hugh Neilson, tulumların hevesli bir oyuncusuydu ve müziği çevredeki çiftliklerin çoğunda, malikanelerin bahçelerinden yükselen müzik duyuluyordu. Ayrıca kıvrılmayı çok severdi ve hava yeterince soğuduğunda tüm yerlileri kıvrık havuzunda bir maç ve dram için aşağı davet ederdi (Hastings 1995). Ev otel iken beton ve asfalt kullanılarak restore edildiğine inanılıyor.

Chapeltoun Estate, Chapeltoun Mains, High Chapeltoun, ev çiftliği (şimdi Chapelhill House), Chapelburn Cottage, Chapelton Farm'dan Mosshead, Bogside yazlık ve Bogflat'ı içeren hiçbir zaman çok büyük olmadı. Cankerton (Cankertonhole) ve Bloomridge (Bloomrig) Kennox Estate'in bir parçasıydı. 1924 ile 1960 yılları arasında Neilsons, Linn House'a sahipti. Dalry.[33]

Bogside kulübesinde Bay Troop ve ailesi ve daha sonra Chapeltoun Mains'de çalışan Bay McGaw yaşadı. Chapeltoun House bahçıvanıydı. Bir ormancı olan Bay Thow (Thor olarak telaffuz edilir) ailesiyle birlikte Bogflat Çiftlik Evi'nde yaşıyordu. Bir şoför, bir Bay McLean, Chapelburn kulübesinde yaşıyordu.[34] ve Firbank, olası (kayıtsız) dikili bir taşla küçük bir koru olarak mevcuttu.

An incident remembered by Mrs. Wilson is that of Mr. Neilson challenging a young man from Kilmaurs to a fist fight because he had found that the man was courting one of his housemaids.

The 'mansion' house of 1910 has had a number of changes of use after it was a private house, being the headquarters of an insurance company and a hotel under several different owners, before becoming a family home again around 2004. The Lobnitz family of Chapeltoun House moved to High Clunch. The Third Statistical Account of 1953 still records Chapeltoun as being one of the six main estates in the parish of Stewarton.

Bahçeler ve manzara

A finial from Chapelton House or possibly a 'wheat sheaf' from the old Monks' Well is used as a feature in the gardens.[32] Apart from pure ornamentation the son can also function as a lightning rod, and was once believed to act as a deterrent to witches on broomsticks attempting to land on one's roof. On making her final landing approach to a roof, the witch, spotting the obstructing finial, was forced to sheer off and land elsewhere. An old lintel from a door is recorded in 1939 as being built into a wall in the garden with the inscription 'S.M. 1740', possibly standing for one of the 'Miller' family'.[32]

The Monks' well

In the woodland policies of Chapeltoun House is the Monks' Well (OS 1974), fountain or spring as indicated on the OS maps going back as far as 1858. Its present appearance is probably as a Victorian or Edwardian 'whimsy' or 'aptallık ' with a large, thick sandstone 'tombstone appearance' with a slightly damaged cross carved in relief upon it and a spout through which the spring water once passed into a cast iron 'bowl'. The Kilmarnock Glenfield Rambler's visited Chapeltoun in 1939 and recorded that a gargoyle had once been present as a spout and that the 'cross' was actually a 'wheat sheaf' that had stood on top of the stone.[32]

It seems unlikely from the workmanship that the well's stone and 'cross' have anything to do with the old chapel, but one possibility is that it came from over the entrance door to Laigh Chapelton as the custom was for a Templar property to have the 'cross' symbol of the order displayed in such a fashion.[4] On the other hand it could have been made for the Chapelton (old) House to associate the building with the Christian history of the site. The stone is unusually thick and has been clearly reworked to pass a spout through it.[36]

işletim sistemi record that in the 1970s a Mr. H.Gollan of Chapeltown stated that the 'Monk's Well', was believed to have been associated with the chapel. In July 1956 the OS state that the 'Monk's Well' is a spring emerging through a stone pipe, situated in a stone-faced cutting in the hill slope. Above the spring is a stone slab with a cross in relief.

The Curling pond

A well is marked near the Chapelton (old) House which became a pump later and may now be represented by a surviving stone lined well with steps leading down to it. The water from this well was used to fill the Curling Pond which was built by the Neilsen's on the site of the original driveway into the old house/farm. It is said that the curling pond was constructed on the site of the old stables.[32]

At the top edge of riverside meadow are to be found a couple of sizeable buzul düzensizlikleri, which were dug out during the construction of the sewerage treatment plant. The remains of the abutments of a footbridge across the river are visible where the garden boundary hedge meets the Annick and Florence Miller remembers the bridge as still standing in the late 1920s. This presumably Victorian or Edwardian feature would take people across to the area delineated by a small ha-ha, now thick with orman gülleri (R.ponticum), typically planted by estate owners.

The ha-ha

Üzerinde Lambroughton side of the river is a substantial wall with a wide ditch in front, built with considerable labour and of no drainage function. This structure was probably a ha-ha (sometimes spelt har har) or sunken fence which is a type of boundary to a garden, pleasure-ground, or park so designed as not to interrupt the view and to not be seen until closely approached. The ha-ha consists of a trench, the inner side of which is perpendicular and faced with stone, with the outer slope face sloped and turfed – making it in effect a sunken fence. The ha-ha is a feature in many landscape gardens laid and was an essential component of the "swept" views of Lancelot Yetenek Kahverengi. "The contiguous ground of the park without the sunk fence was to be harmonized with the land within; and the garden in its turn was to be set free from its prim regularity, that it might assort with the wilder country without". Most typically they are found in the grounds of grand country houses and estates and acted as a means of keeping the cattle and sheep out of the formal gardens, without the need for obtrusive fencing. They vary in depth from about 5 feet (Chapeltoun House) to 9 feet (Petworth).

The old driveway to Lainshaw House off the Stewarton to Torranyard road also has a ha-ha on the side facing the home farm before it reaches the woods. The name ha-ha may be derived from the response of ordinary folk on encountering them and that they were, "...then deemed so astonishing, that the common people called them Ha! Ha's! to express their surprise at finding a sudden and unperceived check to their walk." An alternative theory is that it describes the laughter of those who see a walker fall down the unexpected hole. A seat may have been situated by the ha-ha and the woodland view would have been, and indeed still is, very attractive as this area is clearly an ancient woodland remnant. The stone boundary wall stops in line with the ha-ha.

Chapeltoun Bridge

The Chapeltoun Bridge over the Annick and is a carefully designed sandstone structure complementing the scene. 'Stepping stones' are marked on the 1897 OS map as being located just downstream from here. The name Annick, previously Annock, Annoch (1791) or Annack Water, possibly derives from the Gaelic abhuin, meaning water and oc veya aig meaning little or small. The valley which this river runs through was once called Strathannock.[4] Immense labour has been expended building walls on either side of the river and even the Chapel Burn bed is 'cobbled'.

'Fossilised' linear bands of stone deposition in gardens which were part of this 'boundary' field suggest that the old Teçhizat ve karık system was used hereabouts, however extensive modern ploughing has hidden the 'tell tale' signs.[37] The amount of stone clearance in the 'Lambroughton Woods' bearing plough scoring, illustrates the extent of the ploughing. Other fields in the area still show these unmistakable signs of cultivation and place names such as Lochrig (now Lochridge) and Righead Smithy preserve the history of the practice.

Doğal Tarih

The area of 'wild-wood' beyond the ha-ha, with its 'sheets of bluebells', the wood rushes, wood sorrel, dog's mercury, snowdrops, celandine, broad buckler, lady and male-shield ferns, helleborine orchids and other species typical of long established woodlands, abruptly ends at the 'march' (estate boundary) indicated by a large earth bund and a coppiced boundary beech. The 1858 OS shows the wood as confined to the area of the ha-ha, however by 1897 the OS shows woodland as far up as the march. The Lambroughton woods beyond (until recently the property of the Montgomery / Southannan Estate) are not shown on the older maps including the 1911 OS, they are shown in the 1960 OS map as a pine plantations[38] amongst what was scrub or partial woodland cover containing elder, gean, ash, etc. Before this time the area above the river was not even fenced off at the top where it becomes 'level' with the field.

The Coach Road through the policies near the Lainshaw ha-ha prior to the creation of the SWAT paths.

Chapeltoun Bridge and the River Annick from Chapel Hill.

The woods above the River Annick as viewed from East Lambroughton.

The Coppiced Boundary March beech Tree.

A view of the old Glazert ford at Haysmuir, with the Bonshaw woodlands in the background. One rail is left of an old footbridge.

olmasına rağmen dev hogweed is taking hold along the Annick (2006), however the riparian (water side) flora is still indicative of long established and undisturbed habitats. The rare crosswort, (a relative of the goosegrass or cleavers) is found nearby. The river contains, amongst others, brown trout, sea trout, salmon, eels, minnows, and stickleback. The water quality is much improved since the Stewarton cloth mills closed and the river no longer carries their dyes and other pollutants as shown by the presence of freshwater limpets and shrimps, together with leeches, caddis fly larvae and water snail species.

Yalıçapkını have been seen just downstream and the estate's woodland policies and river contain, amongst others, tawny and barn owls, herons, mallard, ravens, rooks, treecreepers, buzzards, peewits or lapwings, roe deer, mink, moles, shrews, grey squirrels, hares, hedgehogs, foxes, porsuklar, pipistrelle bats and probably su samuru. Migrating Canada and Greylag kazları frequent the nearby fields on their way up from the Caerlaverock or coming down from Spitzbergen kışın. Duncan McNaught[37] in 1895 records that he found a kingfisher's nest at an arms length inside an earthen burrow at Chapelton on the Annick.

The estate woodlands contains typical species, such as copper beech, horse-chestnut, yew, bay-laurel, oaks, ornamental pines, and a fine walnut. Several very large beeches and sycamores are also present. Glenfield Ramblers recorded two especially rare species in the area of the Lainshaw Estate, the lesser wintergreen ve kuş yuvası orkide. Unfortunately no precise details of the site were recorded.[39]

The hedgerow trees accepted today as part of the familiar landscape were not planted by farmers for visual effect, they were crops and the wood was used for building and fencing and the millers needed beech or hornbeam wood for mill machinery, in particular for the sacrificial cogs on the main drive gears. It is not generally appreciated how much the Ayrshire landscape has changed its character, for even in 1760–70 the İstatistik Hesabı it is stated that "there was no such thing to be seen as trees or hedges in the parish; all was naked and open".

The Glazert burn, previously Glazart or Glassert[40] has otters and the rare tatlı su midyesi (source of freshwater pearls). The name may come from the celtic, cam in Gaelic meaning grey or green and dur meaning water. It is recorded by Dobie in 1876 as being a favourite resort of fishermen and this is still very much the case today (2006). Another River Glazert, runs through a considerable part of the parish of Campsie, emptying itself into the Kelvin, opposite the town of Kirkintilloch.

A number of small woodlands are marked as 'fox coverts', such as below Chapeltoun Mains and near Anderson's Plantation, left for foxes to breed and shelter in safety. The local Eglinton avlanmak used to meet at Chapeltoun House.[41][42]

The Toll Road and Milestones

Wheeled vehicles were unknown to farmers in the area until the end of the 17th century and prior to this sledges were used to haul loads[43] as wheeled vehicles were useless. Roads were mere tracks and such bridges as there were could only take pedestrians, men on horseback or pack-animals. The first wheeled vehicles to be used in Ayrshire were carts offered gratis to labourers working on Riccarton Bridge in 1726. In 1763 it was still said that no roads existed between Glasgow and Kilmarnock or Kilmarnock and Ayr and the whole traffic was by twelve pack horses, the first of which had a bell around its neck.[44] Değirmen değirmeni, birkaç kişinin taş ocağından değirmene değirmen taşı rolünü üstlendiği ve buna izin vermek için bazı eski yolların genişliğinin bir 'değirmen değirmeni genişliğine' ayarlandığı bir aks görevi gören yuvarlak tahta parçasıydı.

The Stewarton to Torranyard (Torrenzairds in 1613) road was a turnpike as witnessed by the farm name Crossgates (Stewarton 3 and Irvine 51⁄4 miles), Gateside (near Stacklawhill Farm) and the check bars that are shown on the 1858 OS at Crossgates and at the Bickethall (previously Bihetland) road end to prevent vehicles, horse riders, etc. turning off the turnpike and avoiding the toll charges. A small toll house is shown at Crossgates, now demolished, on the left when facing Torranyard. In Scots a 'bicket' is a 'pocket', an appropriate description of the area the farm lies in. A modern cottage nearby is called 'Robelle' after the farmers Robert and Isabelle from Bickethall.

'Turnpike' adı, bir ucunda destek direğindeki bir menteşeye tutturulmuş basit bir ahşap çubuk olan orijinal 'kapıdan' kaynaklanıyordu. Menteşe 'açılmasına' ya da 'dönmesine' izin verdi Bu çubuk, o dönemde orduda silah olarak kullanılan 'mızrak'a benziyordu ve bu nedenle' paralı 'oluyor. Bu terim ayrıca ordu tarafından özellikle atların geçişini önlemek için yollara kurulan bariyerler için de kullanılıyordu. Other than providing better roads, the turnpikes settled the confusion of the different lengths given to miles,[45] which had varied from 4,854 to nearly 7,000 feet (2,100 m). Long miles, short miles, Scotch or Scot's miles (5,928 ft), Irish miles (6,720 ft), etc. all existed. Another point is that when the toll roads were constructed the Turnpike güvenleri went to considerable trouble to improve the route of the new roads and these changes could be quite considerable. Yollardaki geçiş ücretleri 1878'de kaldırıldı ve yerini 1889'da İlçe Meclisi tarafından devralınan bir yol değerlendirmesi aldı.

Colonel McAlester was a member of the Turnpike Trust and no doubt exerted considerable influence over the route of the turnpike and other matters. John Loudon McAdam was very actively involved with Scottish Turnpikes, living at Sauchrie near Ayr until he moved to Bristol to become Sörveyör to the local Turnpike Trust in 1826.

None of the toll road milestones are visible because they were buried during the İkinci dünya savaşı to prevent them from being used by invading troops, agents, etc.[29] This seems to have happened all over Scotland, however Fife was more fortunate than Ayrshire, for the stones were taken into storage and put back in place after the war had finished.[46] The milestone near Bloomridge Farm and Kirkmuir Farm are likewise missing, presumed buried.

Kirkmuir, Kirkhill, Gillmill, Righead and the Freezeland Plantation

Close to Kirkmuir (previously Laigh Kirkmuir), a farm occupied by William Mure in 1692,[7] is the Freezeland plantation (previously Fold Park) on the turnpike as marked on the 1858 OS. Nowadays it is a smallholding without a dwelling house. The origin of the name is unclear, although 'furz' or furs' is old Scots for karaçalı veya whin, however the existence of this small patch of fenced off land may be linked to the reference in Thomson's 1832 map to a fold, either for sheep or cattle. In 1799 the surrounding field is known as Fold Park.[47] It could have been a pen for strayed stock or be connected with the tolls on the turnpike in some way or a 'stell', the Scot's word for a partial enclosure made by a wall or trees, to serve as a shelter for sheep or cattle. A building may have existed here. Kirkmuir was farmed by John Brown (died 21 August 1880, aged 54) and his wife Catherine Anderson (died 27 August 1895, aged 72). James Walker (died 11 December 1926, aged 86) and his wife Mary Woodburn (died 27 April 1899, aged 57) also farmed Kirkmuir. They were all buried in the Laigh Kirk graveyard.

The field between Kirkmuir & Righead was known as Lady Moss Meadow.[47] Righead was a tollhouse at a later stage, however it was built as a 'butt and ben'. Skirmshaw is the name of some fields nearby in 1797, although no building appears to be present at that time. Picken's (formerly Padzean) Park was across the road from Righead, behind the estate tree boundary. Picken (Padzean) is a fairly common local name (see Kirkhill). Millstone Flat Park is the field above the chalybeate spring on its side of the Ha Ha.through Lady Moss Meadow[47] Kirkmuir was originally a farm on the Longridge Plantation near Highcross Farm (Thomson 1832), later becoming Little Kirkmuir and being marked but not named by 1895, before ceasing to be recorded at all on the OS maps by 1921.

A 'Kirkhill' dwelling is last marked on the 1858 and 1895 0S, below Kirkhill and near to South Kilbride. Andrew Picken was the farmer here in 1867, when his spouse, Ann Blair died, aged 59; she was buried at the Laigh Kirk in Stewarton. It was close to a small burn running from Water Plantation, above Stewarton, in a sheltered glen, typical of early religious settlements and the Kirkhill itself, which was wooded in 1858, is an excellent viewpoint. A track led up to it from Gillmill Farm and it had an entrance near that of South Kilbride. Robert Stevenson farmed at Gillmill and died on 27 May 1810, aged 48.

The plethora of religious names in this area – the Kirkmuirs, Kirkhill, Lady Moss, High Cross, Canaan and the Kilbrides, suggest that at some point in the distant past a pre-Christian and Christian site was located here. No documentary evidence appears to survive and the earliest record is for Kirkry in 1654, now Kilbride. Gelin, Brigit veya St. Brigid, aslen bir Kelt Tanrıçasıydı. Imbolc, the eve of the first of February. She was the goddess of spring and was associated with healing and sacred wells. The Carlin Stone[48] at Commoncrags in Dunlop is associated with the 'old winter hag', the antithesis of the goddess Bride.[49] The name Canaan at Kirkmuir was in use as early as 1779. In 1922 James Martin and Mary Gilmour purchased Gillmill and Canaan from the Cunninghames of Lainshaw.[50]

High Cross was occupied by the Harvies in 1951, who had purchased the farm from the Nairnshaw Estate in 1921. According to Strawhorn they had reconditioned the old thatched farmhouse in 1915 and added a gravitation water supply, bathroom, telephone and electricity. The farm buildings are now (2006) abandoned and the site awaits a new use.

Mineral wells and the source of the Chapel Burn

Paterson[8] (1866) states that there is a mineral spring near Stewarton, called the Bloak Well. Robinson[5] gives the Scot's word 'blout' as meaning the 'eruption of fluid' or a place that is soft or wet. Both meanings would fit in this context. Blout and Bloak are very similar words, with a Bloak Moss not very far away at Auchentiber.

A well recorded as Bloak Well was first discovered in 1800,[9] around 1826 (Paterson 1866) or 1810[51] or 1800, by the fact that pigeons from Lainshaw House and the neighbouring parishes were found to flock here to drink. Mr. Cunningham of Lainshaw built a handsome house over the well in 1833 and appointed a keeper to take care of it as the mineral water was of some value owing to healing properties attributed to it. The well was located in the middle of the kitchen.[52][53]

The Chapel Burn rises near the Anderson Plantation in the fields below Lainshaw Mains and it is marked as a kalybeat or mineral spring on the 1911 6" OS map. Bore holes nearby suggest that the water was put to a more formal use at one time, supplying cattle troughs or possibly even for a stand pipe as mineral water was popular for its supposed curative properties. According to the opinion of the day, it could cure 'the colic, the melancholy, and the vapours; it made the lean fat, the fat lean; it killed flat worms in the belly, loosened the clammy humours of the body, and dried the over-moist brain. The main spring here has been covered over and the water piped out to the burn.[54]

kalybeat spring (otherwise known as Siderit, a mineral consisting of iron(II) carbonate, FeCO3 – 48 percent iron) described here is not the only well / spring in the area which is identified as being a mineral spring, for there is still a cottage named Saltwell in what was the hamlet of Bloak. This information is stated by the Topographical Dictionary of Scotland, however Mrs. Florence Miller of Saltwell recollects that this well was never known specifically as the Bloak Well.[55] The present building was purchased from the Cunninghames of Lainshaw in the 1920s, having been built between 1800 and 1850. It is thought that the salt well now lies beneath the floor of the building and various physical features of the building suggest that it is the structure built by the Cunninghames. The well was first discovered by the fact that migrating birds, especially swifts and swallows, flocked to it.[56] It is of unknown composition and is not listed as chalybeate. The cottage was a 'but and ben' and it is a 'handsome' building as described by Paterson. A Redwells Farm is located nearby at Auchentiber, the etymology of tiber itself refers to a well.[57]

1930'da Kilmarnock Glenfield Ramblers' Society kaydetmek Ramble during which they walked past the well known local spring, its waters rich in iron, on their way to the Kennox Estate, having already visited the Lainshaw Estate.[39] This must be the source of the Chapel Burn.

The March Dyke and a dispute between neighbours

The Chapeltoun march is a significant historic survival in an Ayrshire context and in addition we have some information about its construction.[17] Defence for James Wilson Sued by John Miller 7th. August 1820. Manuscript and personal communications. We are told in 1820 that "the march dyke was built some many years ago when such boundaries were quite a new thing and thought by some to be rather an incovenience". Ditchers were employed to build it and thorns and trees were purchased to plant on it. The word fence is used as well as dyke in regards of the construction method. Part of the march dyke is still clearly indicated by a large coppiced beech and we know that this coppicing or pollarding was done because such 'marker' trees will live considerably longer than trees which have been left untouched.

James Wilson of High Chapelton and John Miller of Laigh Chapelton went to court over the matter of the march dyke built between their lands by the father of James.[17] The document makes it clear that such inclosures were unusual at the time and although John's father very reluctantly agreed to the march dyke being built with a straightening of the old boundary, he did not pay anything towards its construction or for its maintenance, despite the march being of a level of construction which required skilled ditchers to be employed for the task.

The ill-feeling seems to have spread into the next generation for James records that John has cut 'march' trees down in the past and has thrown thorns and brambles from the march into the High Chapeltoun's hayfields. The irony is that John of Laigh Chapelton is suing James for cutting down trees from the march dyke and requires money to plant new trees and to compensate for the inconvenience he has been put through. We do not know the outcome, however the action is described as "trifling and frivolous". The clue to the ill-feeling may be in the term 'straightening' which may imply that John's father agreed to a new march which may have resulted in some small loss of his lands.

The rental value of High Chapelton was £137 in 1820 and Laigh Chapelton was £180. The memorial stone to the Miller family of Chapelton (Chapelton is the spelling on the tombstone) is very well preserved at the Laigh Kirk, Stewarton. John Miller died on 3 December 1734, aged 30, and his spouse, Jean Gilmour died on 24 November 1747, aged 42. Their son James died on 1 November 1793, aged 60, and his spouse, Margaret Gilmour, died on 1 April 1802, aged 61. Their son John is the one involved in the dispute; he died on 25 December 1825, aged 59. His spouse was Grizel Gray, who died on 7 January 1855.

The march dyke is clearly marked on the 1885 OS map, following the course of the bank above the water meadow from the riverside and then running up as a 'v' shape towards High Chapeltoun before coming back down to join the lane near the Chapel mound. It doesn't follow the line of the natural ridge above the waterside meadow.

Aiton in 1811 mentions "a curious notion that has long prevailed in the County of Ayr, and elsewhere, that the wool of sheep was pernicious to the growth of thorns" (hawthorn or whitethorn and blackthorn or sloe).

Other sites of interest in the area

Crivoch Mill

| Etimoloji |

| İsim Crevoch most likely derives from the Scots Gaelic for place of the trees, indicating that a substantial wooded area existed in the locality in times past. |

Crivoch or Crevoch (also Crevock in 1821[11]) mill, part of which was recently (2005) rebuilt as Angel Cottage, a family home, was the site of a Mill and associated miller's dwelling, byre, etc. as far back as 1678. 'Cruive' is Scots for a pen for livestock.[58]

The old cornmill was part of the Barony of Crevoch and lay in the portion which was called Crivoch-Lindsay. In 1608 Archibald Lindsay was heir to Andrew Lindsay the owner, however by 1617 the lands were in the hands of James Dunlop, whose father was James Dunlop of that Ilk.In January 1678 Robert Cunynghame, apothecary / druggist in Edinburgh, is stated to be the heir to Anne, daughter of Sir Robert Cunynghame of Auchenharvie. She was his cousin-german and part of the inheritance was the 5 merk land of Fairlie-Crivoch and the mill. He also owned some of the lands of Lambroughton ve Auchenharvie yakın Cunninghamhead / Perceton. A Robert and Jonet Galt are recorded as living at Crivoch in around 1668.[7] In 1742 William Millar, Baillie, was 'Milner in Crivoch Miln'.[21]

The mother of the late Mrs. Minnie Hastings of West Lambroughton Farm[59] had been one of the last occupants of the house at the Crevoch Mill site. The family name was Kerr. A track led from Crivoch up to Bottoms farm and this gave access through to Chapeltoun. The full name of Bottoms farm is Bottoms at Point Crivoch. dusky cranesbill, a rare garden escape, was recorded by the Glenfield Ramblers' at Crivoch mill in the 1850s and was still growing at the site in 2004.

In 1735 John Cummin, a schoolmaster, is recorded as living at Crivoch.[21]

The Gallowayford Cists and Farm

| Etimoloji |

At Gallowayford near Kennox is the site of the discovery in 1850[9] of stone-lined graves about 3 feet (0.91 m) square, in a group of tumuli, in which were found two urns containing flint arrowheads and some 'Druid's glass' beads. Charles McAlister Esq. of Kennox House, the laird, had ordered these graves to be opened and examined. The flints and the eleven beads (probably made of amber) have been lost after having been taken into the keeping of the laird. They had at least been photographed and sketched by a visitor in the 1920s. The urns were also feared lost; however, it was found that they had been recorded under Loup and not Kennox (as the owner was Laird of both places) in the record of the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland. In 1949 they had been purchased from the estate. This find is one of the very few where two urns were found in the same cist, and the assemblage of grave goods is unusual.[60] Gallowayford Farm is no longer in existence; however, the remains of the dam or weir in the Glazert nearby can be clearly seen. Robertson (1820) regards this as being a valuable property, the proprietor being James Millar, with a valued rent of £21.[61]

Close to the cists site is the Mound Wood on Kennox Moss, an oval shaped artificial structure made of piled turf and surrounded by a well constructed drystone wall. It has not been investigated archaeologically. An access track ran up to it at one time and Roy's map of 1747 indicates that a dwelling known as Water House existed in this vicinity at that time.

The Gallowayford Farmhouse is now (2006) just a jumble of stones, however John Shields and his spouse Jean Guthrie farmed here in the mid-19th century, Jean dying on 4 October 1887 and John on 22 September 1908; they lost a daughter, Isabella at the age of 4 in 1862. James Miller farmed here previously, dying on 3 April 1813. They are all buried at the Laigh Kirk in Stewarton. General Roy's map of 1747–55 clearly shows Gallowayford and Irvinhill.

Bonshaw

Bonshaw (formerly Bollingshaw or Bonstonshaw) was a small estate and barony of the Boyd's, a cadet of the Boyds, Lords of Kilmarnock.[4]

Stacklawhill

Near Stacklawhill is the site of the discovery of celts (axe heads) and earthenware in 1875. John Craufurd Taylor is recorded as living at Stackly hill in 1735. Mr Muir of Bonnyton farm was the great-grandson of Mr Thomas Reid of Stacklawhill farm who had owned the Bonnyton estate in 1827. The properties of Mossend Huist and Bogue were incorporated within Stacklawhill.[62]

Bankend or Sandilands Farm

Bankend Farm near the Annick is marked on the 1775 Armstrong's[2] map, however it shown as a ruin as far back as 1858. Its name was transferred to the farm of Sandilands sometime after 1923 and the name Sandielands (1820), Sandilands or Sandylands dropped, 'apart' from the cottage nearby which uses the name Sandbank. Nothing of old Bankend remains on the site, the rubble now being located on the riverbank. A Hugh Watt lived here in the 18th century.[21] The Sandilands family, with the title Lord Torphichen, held the temple-lands and this would have included "the chapel lands and glebe of Fairlie-Crivoch." The soil in these parts is not sandy and the land ownership may very well be the explanation for the origin of the placename given the connection between the Sandylands or Sandilands family and the former Knights Templar estates. The Lainshaw Estate plan of 1779–91 by William Crawford for William Cunningham Esq. names the area as Sandylands and marks a steading called Sandiriggs.[47] The farms of Bankend and Sandylands became combined as the property of Sandilands.[63]

A ford crossed the river at this point, the road then running up the hill to West Lambroughton. This was an important crossing as no bridge, road or ford existed at Chapeltoun until possibly the time of the building of Chapelton House in the 1850s.

Clonbeith Kalesi

Given as 'Klonbyith' by Pont in the 1690s Clonbeith was then the property of William Cuninghame, Filiz of this cadet branch of the Glencairn Cuninghames through those of Aiket Castle. John Cuninghame shot and killed the Earl of Eglinton in 1586 and was caught and 'cut to pieces' in Hamilton, possibly at Hamilton palace.[4][64]

The Cowlinn burn runs down to join the Lugton Water at the site of Montgreenan castle or the Bishop's Palace. A dwelling called Cowlinn is marked on the Thomson's 1820 map and a Clonbeith Mill was nearby.

Stewarton area local and social history

Limekilns are a common feature of the area and limestone was quarried in a number of places, such as at Stacklawhill. Limekilns seem to have come into regular use about the 18th century and were located at Stacklawhill, Haysmuir, Bonshaw, High Chapeltoun, Bloomridge (Blinridge in 1828), Gillmill, Sandylands (now Bank End) and Crossgates. Large limestone blocks were used for building but the smaller pieces were burnt, using coal dug in the parish[51] to produce lime which was a useful commodity in various ways: it could be spread on the fields to reduce acidity, for lime-mortar in buildings or for lime-washing on farm buildings. Temizleyici olarak kabul edildi. A number of small whinstone, sand and sandstone quarries were also present in the area and brick clay was excavated near Kirkmuir.[65]

Aiton in 1811 comments on the growing of carrots by William Cunningham of Lainshaw as an 'excellent article of food for the human species'. This was one of the first estates to grow them in quantity.

In 1820 only six people were qualified to vote as freeholders in Stewarton Parish, being proprietors of Robertland (Hunter Blair), Kirkhill (Col. J. S. Barns), Kennox (McAlester), Lainshaw (Cunninghame), Lochridge (Stewart) and Corsehill (Montgomery Cunninghame).

Modern Sanat Galerisi (GOMA) is a neo-classical building in Royal Exchange Square in the Glasgow city centre, which was built in 1778 as the townhouse of William Cunninghame of Lainshaw, a wealthy tobacco lord. The building has undergone a series of different uses; Tarafından kullanıldı İskoçya Kraliyet Bankası; it then became the Royal Exchange. Reconstruction for this use resulted in many additions to the building, namely the Korint sütunları to the Queen Street facade, the cupola above and the large hall to the rear of the old house.

Shoes were only used for Sunday best and for many of the younger folk going bare foot was the order of the day. The family at High Chapeltoun were one of the last to do this on a day to day basis.[66]

The Royal Mail re-organised its postal districts in the 1930s and at that point many hamlets and localities ceased to exist officially, such as Chapeltoun, Lambroughton and other areas in Stewarton district.[43]

James Boswell nın-nin Auchinleck Evi, the famous biographer and friend of Dr. Samuel Johnson was married to his cousin Margaret Montgomerie in Lainshaw Kalesi. He had gone to Ireland with Margaret, with the intention of courting another wealthy cousin, however he fell in love with the penniless Margaret and married her instead. The room they were married in was one floor above the room in which the Eglinton Kontu was laid after he was murdered by Kurnazlık at the old brig or ford on the Annick Water near the entrance to the castle on the Stewarton yol.[39] David Montgomery of Lainshaw married a daughter of Lord Auchinleck.

John Kerr of Stewarton ilk uygulamayı inşa etti arı kovanı in the World in 1819, octagonal in shape with a bee-space and a queen separator introduced by 1849. The shape was thought to be closest to the natural tree-trunk shape which bees were thought to favour. L. L. Langstroth is often credited with these developments, however an examination of the records shows that John Kerr, a cabinet maker, was the first to use these features in a working hive.[67] Beeboles and straw skeps were used previous to these developments and here the bees had to be killed to obtain the honey.Running from Anderson's Plantation across the hill and back down to the old driveway near to the duvarlı bahçe is a wall or dyke replacing a tree lined hedge shown in 1858. The wall or dyke is very unusual in that it is made from roughly equal sized rounded whinstones and it is held together by cement. A great deal of expense and effort would have been needed to build this long section of dyke, which seems to have been in place by 1911.

The estate wall running from near Freezeland to near the Law Mount was built by unemployed labourers in the early 19th century.

Rudolf Hess 's Messerschmitt Bf 110 was spotted by locals as he flew on his mission from Nazi Germany to meet with the Hamilton Dükü in 1941. He crashed in Eaglesham on Floors Farm.

Ayrıca bakınız

- Cunninghamhead

- Lambroughton

- Corsehill

- Yerel Tarih terminolojisi için bir Araştırmacı Kılavuzu

- Cunninghamhead, Perceton ve Annick Lodge

- Stewarton

Referanslar

- ^ Dillon, William J. (1950). The Origins of Feudal Ayrshire. Ayr Arch Nat Hist Soc V.3. P. 73.

- ^ a b c d e Armstrong ve Oğul. Engraved by S.Pyle (1775). Kyle, Cunningham ve Carrick'i kavrayan Ayr Shire'ın Yeni Haritası.

- ^ Barber, Malcolm (1996). Yeni Şövalyelik. Tapınak Düzeni Tarihi. Pub. Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-55872-7. P. 304.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Kurnazlık, Timothy Pont tarafından Topografya 1604–1608, devamı ve açıklayıcı bildirimlerle. Pub. John Tweed, Glasgow.

- ^ a b Robinson, Mairi (2000). The Concise Scots Dictionary. Aberdeen. ISBN 1-902930-00-2.

- ^ Pont, Timothy (1604). Cuninghamia. Pub. J. Blaeu.

- ^ a b c Commisariot of Glasgow Wills from the Commissariot of Glasgow 1547.

- ^ a b c d e f Paterson, James (1863–66). Ayr ve Wigton İlçelerinin Tarihi. V. – III – Cunninghame. Edinburgh: J. Stillie.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, John (1895). Ayrshire'daki Tarih Öncesi Adam. Pub. Elliot Stock.

- ^ Arrowsnith, Aaron (1807). A Map of Scotland Constructed from original Materials.

- ^ a b Ainslie, John (1821). İskoçya'nın Güney Kısmının Haritası.

- ^ a b "The RCAHMS's Canmore Website". Alındı 16 Mart 2007.

- ^ Steven, Rev. Charles Bannatyne (Revised 1842). Parish of Stewarton. Presbytery of Irvine, Synod of Glasgow and Ayr

- ^ Fullarton, p.77

- ^ Paterson, Page 54

- ^ Edinburgh Gazette No.3655, Page 153

- ^ a b c d Smith, Barbara and David. (2006) Oral communication.

- ^ a b Robertson, George (1820). A Topographical Description of Ayrshire; more particularly of Cunninghame. Pub. Cunninghame Press, Irvine. Sayfa 317.

- ^ a b Davis, Michael C. (1991). The Castles and Mansions of Ayrshire. Pub. Spindrift Press, Ardrishaig, Pps. 206 & 207.

- ^ Smith, William (2009). Sözlü bilgiler. Bottoms point Crevoch Farm.

- ^ a b c d e Chapeltoun Mains Archive (2007) – legal documents of the Lands of Chapelton from 1709 onwards.

- ^ Hogg Patrick Scott (2008). Robert Burns The Patriot Bard. Edinburgh: Ana Yayıncılık. ISBN 978-1-84596-412-2. s. 75.

- ^ McAlester (1827). Correspondence to William Patrick Esq., Albany Street, Edinburgh.

- ^ McDonald, Ian (2006). Roger S. Ll. İle Sözlü İletişim Griffith.

- ^ Search over Lainshaw, Page 273

- ^ Drummond family history. Accessed : 6 January 2010

- ^ İskoçya'nın Yerler. Accessed : 6 January 2010 Arşivlendi 19 Temmuz 2011 Wayback Makinesi

- ^ Smith, David (2003). Peacockbank Farm, Stewarton, North Ayrshire.

- ^ a b Wilson, James (2003). Mid Lambroughton Farm, North Ayrshire.

- ^ Forrest, James (2003). Mid Lambroughton Farm, North Ayrshire.

- ^ Close, Robert (1992), Ayrshire and Arran. Resimli Mimari Rehber. Pub. Royal Inc of Arch in Scotland. ISBN 1-873190-06-9. s. 122.

- ^ a b c d e f Kilmarnock Glenfield Ramblers. 03/06/1939.

- ^ Davis, Page 317

- ^ Wilson, Jenny (2006). Oral Communication.

- ^ Davis, Page 207

- ^ Aşk, Dane (2009). Efsanevi Ayrshire. Custom : Folklore : Tradition. Auchinleck : Carn Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9518128-6-0; s. 62 – 63

- ^ a b * McNaught, Duncan (1912). Kilmaurs Cemaati ve Burgh. Pub. A.Gardner.

- ^ Groome, Francis H. (1885). Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland: A Survey of Scottish Topography. V.6. P. 381.

- ^ a b c Kilmarnock Glenfield Ramblers Society. (1930). V.10. P. 62 & 133.

- ^ Paterson, James (1847). History of Ayr and a Genealogical Account of the Ayrshire Families. P. 452.

- ^ Barclay, Alastair (1989). The Bonnet Toun.

- ^ Fawcett, William (1934), The Eglinton Hunt. Pub. The Hunt Association. Londra. P. 20.

- ^ a b Strawhorn, John ve Boyd, William (1951). İskoçya'nın Üçüncü İstatistik Hesabı. Ayrshire. Pub. Edinburgh.

- ^ Ker, Rev. William Lee (1900) Kilwinnning. Pub. A.W.Cross, Kilwinning. P. 267.

- ^ Thompson, Ruth & Alan (1999). The Milestones of Arran.

- ^ Stephen, Walter M. (1967–68). Milestones and Wayside Markers in Fife. Proc Soc Antiq Scot, V.100. P.184.

- ^ a b c d İskoçya Ulusal Arşivleri. RHP/1199.

- ^ Mack, James Logan (1926). Sınır Çizgisi. Pub. Oliver ve Boyd. P. 215.

- ^ Ralls-McLeod, Karen & Robertson, Ian. 2003. Kelt Anahtarı Arayışı. Luath Press. ISBN 1-84282-031-1. S. 146.

- ^ Search over Lainshaw, Page 313

- ^ a b Topographical Dictionary of Scotland (1846). P. 467

- ^ Houston, John (1915), Auchentiber Moss, 14 August 1915. Annals of the Kilmarnock Glenfield Ramblers Society. 1913–1919. P. 112.

- ^ Aşk, Dane (2009). Efsanevi Ayrshire. Custom : Folklore : Tradition. Auchinleck : Carn Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9518128-6-0; s. 52–53

- ^ Aşk, Dane (2009). Efsanevi Ayrshire. Görenek: Folklor: Gelenek. Auchinleck : Carn Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9518128-6-0; s. 53

- ^ Miller, Florence (2006). Oral Communications to Roger S.Ll. Griffith.

- ^ Miller, Floransa (2006). Sözlü iletişim.

- ^ McNaught Duncan (1912). Kilmaurs Cemaati ve Burgh. Pub. A. Gardner.

- ^ Warrack, Alexander (1982). "Chambers İskoç Sözlüğü". Odalar. ISBN 0-550-11801-2.

- ^ Hastings, M (1995). R.S.Ll.Griffith ile kişisel iletişim.

- ^ Ritchie, J.N. (1981/82). Gallowayford, Stewarton, Ayrshire'dan bir Cist. Proc Soc Antiq Scot, V.112. S. 548 -549.

- ^ Robertson, George (1820). Ayrshire'ın Topografik Tanımı; daha fazla Özellikleunninghame: o Bailiwick'deki Müdür ailelerin Soybilimsel açıklamasıyla birlikte. Kurnazhame Basın. Irvine.

- ^ Lainshaw. Sasines Kaydı. 150.Sayfa

- ^ Lainshaw. Sasines Kaydı. Sayfa 282

- ^ Ker, Rev. William Lee (1900) Kilwinnning. Pub. A.W.Cross, Kilwinning. S. 161.

- ^ Thomson, John (1828). Ayrshire'ın Kuzey Kısmının Haritası.

- ^ Avcı, Jessie (1998). Roger S.Ll.'ye Sözlü İletişim Griffith.

- ^ Daha fazla, Daphne (1976). Arı Kitabı. ISBN 0-7153-7268-8.

Kaynakça

- Aitken, John (1829). Cunningham Cemaatleri Üzerine Bir İnceleme. Pub. Beith. S.276.

- Aiton, William (1811). Ayr Tarımına Genel Bakış. Pub. Glasgow.

- Adamson, Archibald R. (1875). Rambles Round Kilmarnock. Pub. T. Stevenson, Sf.168–170.

- Bayne, John F. (1935). Dunlop Cemaati - Kilise, Cemaat ve Asalet Tarihi. Pub. T. & A. Constable, Pps. 10 - 16.

- Davis, Michael C. (1991). Ayrshire Kaleleri ve Konakları. Pub. Spindrift Press, Ardrishaig, Pps. 206 ve 207.

- Edinburgh Gazette. No. 3655. 13 Nisan Cuma. 1828.

- Fullarton, John (1858). Ayrshire, Cunningham Bölgesinin Topografik Hesabı 1600 yılı hakkında Bay Timothy Pont tarafından derlenmiştir.. Glasgow: Maitland Kulübü.

- Groome, Francis H. (1885). Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland: A Survey of Scottish Topography. V.6. S.381.

- MacIntosh, John (1894). Ayrshire Geceleri Eğlenceleri: Ayr İlçesinin Tarihine, Geleneklerine, Eski Eserlerine vb. Açıklayıcı Bir Kılavuz. Pub. Kilmarnock. S. 195.

- Mühimmat Araştırması İsim Kitabı (1856). No. 58, Pps. 58-9,

- Pont, Timothy (1604). Cuninghamia. Pub. J.Blaeu, 1654.

- Robertson, George (1823). Ayrshire'daki Ana Ailelerin Soy Bilimi, özellikle deunninghame'de. Cilt 1. Pub. Irvine.

- Sanderson, Margaret H.B. (1997). Ayrshire ve reform 1490–1600. ISBN 1-898410-91-7.

- Strawhorn, John ve Boyd, William (1951). İskoçya'nın Üçüncü İstatistik Hesabı. Ayrshire. Pub. Edinburgh.

Dış bağlantılar

- Chapel Hill'de video ve yorum

- Chapeltoun ha-ha'nın video görüntüleri

- 'Su Toplantıları' ve Bankend Ford hakkında video ve yorum

- East Lambroughton ve Lambroughtonend'in YouTube videosu

- Lambroughton Woods ve damızlık akbabalar

- General Roy'un haritaları.

- http://www.scottisharchitects.org.uk/building_full.php?id=202307