Mississippi Anayasası - Constitution of Mississippi

| Mississippi Eyaleti Anayasası | |

|---|---|

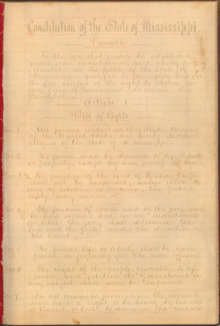

Mississippi'nin 1890 anayasasının ön kapağı. | |

| Oluşturuldu | 12 Ağustos 1890 - 1 Kasım 1890[1] |

| Onaylandı | 1 Kasım 1890 |

| Geçerlilik tarihi | 1 Kasım 1890[a] |

| yer | William F. Kış Arşivleri ve Tarih Binası[2] Jackson, Hinds İlçe, Mississippi, U.S. Frick |

| Yazar (lar) | Süleyman Selahaddin Calhoon[3][4] (1890 kongre başkanı) |

| İmzacılar | Süleyman Selahaddin Calhoon[3][4] (1890 kongre başkanı) |

| Amaç | 15 Mayıs 1868'de kabul edilen ve 1 Aralık 1869'da devlet tarafından onaylanan Mississippian eyalet anayasasını değiştirmek ve geçersiz kılmak. |

Mississippi Eyaleti Anayasasıolarak da bilinir Mississippi Anayasası, için geçerli belge ABD eyaleti nın-nin Mississippi. Mississippian eyalet hükümetinin yapılarını ve işlevlerini açıklar ve sıralar ve eyalet sakinleri ve vatandaşları tarafından sahip olunan hakları ve ayrıcalıkları listeler. 1 Kasım 1890'da kabul edildi.

Mississippi eyalet haline geldiğinden beri dört anayasaya sahip. İlki, Mississippi'nin bir ABD topraklarından bir ABD eyaletinin topraklarına yükselmesi üzerine 1817'de yaratıldı. İkinci anayasanın oluşturulup kabul edildiği 1832 yılına kadar kullanıldı. O zamanlar eyaletteki beyaz erkeklerle sınırlı olan mülk sahipliğini oylama için bir ön koşul olarak sona erdirdi. 1868'de kabul edilen ve ertesi yıl onaylanan üçüncü anayasa, eyalet halkı tarafından onaylanan ve onaylanan ilk Mississippian anayasasıydı ve eyaletin tüm sakinlerine, yani yeni serbest bırakılan kölelere devlet vatandaşlığı bahşedildi. Dördüncü anayasa Kasım 1890'da kabul edildi ve çoğunlukla Demokratlar devletin Afrikalı-Amerikalı vatandaşlarının oy kullanmasını engellemek için. Oy kullanmalarını engelleyen hükümler, 1975 yılında, Amerika Birleşik Devletleri Yüksek Mahkemesi 1960'larda onları yönetti Amerika Birleşik Devletleri Anayasasının ilkelerini ihlal etmiş olmak.

Mevcut Mississippian eyalet anayasası, Kasım 1890'da ilk kabulünden bu yana on iki yıldan fazla bir süre içinde birkaç kez değiştirildi ve güncellendi, bazı bölümler tamamen değiştirildi veya kaldırıldı. Eyalet anayasasında en son yapılan değişiklik Haziran 2013'te gerçekleşti.

Tarih

Bu bölüm genişlemeye ihtiyacı var. Yardımcı olabilirsiniz ona eklemek. (Ağustos 2015) |

Başlamadan birkaç ay önce Amerikan İç Savaşı Nisan 1861'de, ABD'nin güneyinde bulunan bir köle devleti olan Mississippi, Amerika Birleşik Devletleri'nden ayrıldığını ve yeni kurulan Konfederasyon ve daha sonra ABD Kongresindeki temsilini kaybetti. Dört yıl sonra, Birlik sonunda Amerikan İç Savaşı ve kaldırılması kölelik yeni yürürlüğe giren Onüçüncü Değişiklik 1868'de eyalette yeni serbest bırakılan kölelere vatandaşlık ve sivil haklar vermek için yeni bir Mississippian devlet anayasası oluşturuldu. Mississippi, Şubat 1870'te Amerika Birleşik Devletleri'ne tamamen geri kabul edildikten sonra kongre temsilini yeniden kazandı.[5]

Mississippi Eyaleti'nin sahip olduğu üçüncü anayasa olan 1868 eyalet anayasası, 22 yıl boyunca yürürlükte kaldı. 1877 Uzlaşması ve uzun bir kampanya Demokratik yönetimi kurmak için terörist şiddet eyalette başarılı oldu, esas olarak beyazlardan oluşan bir anayasa konvansiyonu Demokratlar özellikle dördüncü ve mevcut anayasayı oluşturdu ve kabul etti devletin Afro-Amerikan nüfusunu haklarından mahrum etmek, izole etmek ve marjinalleştirmek.[6][7][8][9] 1868 anayasasının aksine, 1890 anayasası, onay ve onay için devletin geneline gitmedi. Sözleşme, 1817 ve 1832 eyalet anayasalarında yapıldığı gibi, hepsini kendi inisiyatifiyle oluşturdu, onayladı ve onayladı.

Dördüncü ve mevcut eyalet anayasası, 1890'da ifade edilen amaç için oluşturuldu. serbest bırakılmış kölelere ve onların soyundan gelenlere karşı ayrımcılık, Demokratlar ve eyalet hükümeti tarafından birlikte kullanıldı terörist şiddet, için siyah Mississippi'lilerin devletin sivil toplumuna katılmasını marjinalleştirmek ve yasaklamak seksen yıldır. Değiştirildiği 1868 anayasasından farklı olarak, 1890 anayasası genel olarak devletin halkına onay ve onay için gönderilmedi, daha ziyade onu oluşturan konvansiyon tarafından tamamen onaylandı, benimsendi ve onaylandı.[10] Mississippi, o zamanlar özellikle Afroamerikan seçmenlerinin haklarından mahrum bırakmak amacıyla yeni bir anayasa oluşturan tek ABD eyaleti değildi; diğerleri de yaptı[11] gibi Güney Carolina Aralık 1895'te, Demokratik vali, yerini aldı 1868 eyalet anayasası Tıpkı Mississippi'nin beş yıl önce yaptığı gibi.[11] Mississippi'nin mevcut 1890 anayasasında olduğu gibi, 1895 Güney Carolinian anayasası bugün hala kullanılıyor.[11]

Kabul edilmesinden sonraki seksen yıl boyunca, 1890 anayasası, Demokratların kontrolündeki Mississippian eyalet hükümetine, çoğu Afro-Amerikalının neredeyse her zaman kasıtlı olarak standartların altında kalitedeki ayrı okullara gitmeye zorlamanın yanı sıra oy kullanmasını ve oy kullanmasını engellemek için etkili bir şekilde serbest bıraktı. , diğer etnik gruplardan insanlarla evlenmelerini veya savunma için silah taşımalarını yasakladı.[6][7][12][13][14][15][16] 1950'lerde ve 1960'larda, Birleşik Devletler hükümeti tarafından yapılan soruşturmaların ardından,[1] bu ayrımcı hükümler, ABD Yüksek Mahkemesi Amerikan vatandaşlarına garanti edilen hakları, ABD Anayasası bu da onları yasal olarak uygulanamaz hale getiriyor. Ancak, bunların yasalaşmasından yaklaşık bir yüzyıl sonra, 1970'lerde ve 1980'lerde eyalet hükümeti tarafından nihayet yürürlükten kaldırıldığında yapılan devlet anayasasından resmen çıkarmak birkaç on yıl daha alacaktı.

1890'da kabul edilen Mississippian anayasasını, özellikle 1930'larda ve 1950'lerde yenisiyle değiştirmek için yasama çabaları vardı, ancak sonuçta bu çabalar başarılı olamadı.[17] Birkaç eyalet valisi ve Mississippian politikacı, 1890 anayasasının ayrımcı geçmişi nedeniyle ahlaki açıdan iğrenç olduğu ve devletin parasal ticaretine ve işlerine zarar veren hükümler içerdiği gerekçesiyle 1890 anayasasının değiştirilmesi lehine karar verdiler, Demokratlar tarafından özel şirketleri engellemek için çıkarıldı. eyalet dışından Mississippi'de Afro-Amerikan işçileri işe almaktan ayrımcı dönem.[17] Ancak bu çabalara rağmen, 1890 Anayasası, müteakip değişiklik ve değişiklikleriyle bugün hala yürürlüktedir.[9][17]

1817 anayasası

1817 anayasası, Mississippi'nin ABD eyaleti olarak sahip olduğu ilk anayasaydı ve eyalet 1817'de federal Birliğe katıldığında oluşturulmuştu. 1832'de yerini 1868'e kadar kullanılan yeni bir eyalet anayasası aldı.

1832 anayasası

1832 eyalet anayasası 1868'e kadar yürürlükte kaldı ve seçmenlerin oy kullanmak için mülk sahibi olmaları şartını kaldırdı. Ancak, seçilen göreve seçilme ve aday olma hakkı yalnızca beyaz erkeklerle sınırlıydı. Kadınların ve Afrikalı Amerikalıların eyalette oy kullanmaları veya bu anayasa uyarınca göreve seçilmeleri hâlâ yasaktı.

1832 anayasası, Amerika Birleşik Devletleri'nde kölelik yasal iken kullanılan son Mississippi eyalet anayasasıydı. Köleliğin kaldırılmasından üç yıl sonra, 1868'de yerini yeni bir anayasa aldı.

Hükümler

Yargı

Anayasa, IV. Maddede tanımlandığı gibi, yargıçların seçilme ve artık atanmama şeklini değiştirdi.

Düello

Düello, 19. yüzyılın başlarında Amerika Birleşik Devletleri'nde oldukça yaygın bir olaydı. Alexander Hamilton ve Aaron Burr Birincisinin ölümüyle sonuçlanan bu, şimdi 1832 eyalet anayasasına göre yasadışı ilan edildi. Yeni anayasa, politikacıların bir düelloya girmeyeceklerine dair bir onay vermelerini bile gerektirdi:

Yasama organı, gerekli gördüğü kötü düello uygulamalarını önlemek için bu tür yasaları çıkarır ve tüm görevlilerin kendi görevlerine girmeden önce aşağıdaki yemin veya onaylamalarını isteyebilir: "Ciddiyetle yemin ederim (veya bir düelloya girmediğimi, bir düello gönderip kabul ederek veya Rabbimiz'in bin sekiz yılında Ocak ayının ilk gününden bu yana bir düelloya girmediğimi onaylayın. Yüz otuz üç, ne de görevde kaldığım süre boyunca bu kadar meşgul olmayacağım Tanrım bana yardım et.

— Bölüm 2, Madde VII, Genel Hükümler, Mississippi 1832 Anayasası, (1832).

Dönem sınırları

1838 anayasasına göre seçilmiş bürolar için süre sınırları belirlendi.

Kölelik

1832 anayasası, kendisinden önceki 1817 anayasası gibi, Mississippian eyalet yasama organının, köle devletin yararına "seçkin" bir eylemde bulunmadıkça veya rıza göstermedikçe, insanları kölelikten kurtarmak için tasarlanmış herhangi bir yasayı kabul etmesini yasakladı. kölenin kurtuluşu için parasal olarak tazmin edilecek mal sahibinin:

Köle devlete bazı seçkin hizmetlerde bulunmadıkça, bu durumda köle sahibine köle için tam bir eşdeğer ödeme yapılmadıkça, yasama organının kölelerin sahiplerinin rızası olmaksızın kölelerin kurtuluşu için yasalar çıkarma yetkisi yoktur. özgürleşti. [...]

— Bölüm 1, Madde VII, Genel Hükümler, Mississippi 1832 Anayasası, (1832).

Bu maddenin 1817'den 1832 anayasasına kadar muhafaza edilmesi, eyalet yasama organlarının köle sahiplerinin tam rızası olmadan bunu imkansız hale getirerek eyalet yasama organlarının köleliği sona erdirmesini kısıtlayan yasaların, o zamanki güney halk görüşünün gidişatını yansıtıyordu. kabul edildi veya tutuldu ya da köle sahiplerinin kölelerini serbest bırakmalarını zorlaştıran yasalar da çıkarıldı. Geleceğin Cumhuriyetçi ABD başkanı Abraham Lincoln tarafından 1857 tarihli bir konuşmada belirtildiği gibi Dred Scott karar:

O günlerde, anladığım kadarıyla, efendiler, kendi zevklerine göre, kölelerini özgürleştirebilirlerdi; ancak o zamandan beri, özgürleşme üzerine neredeyse yasak anlamına gelecek şekilde bu tür yasal sınırlamalar getirildi. O günlerde, Yasama Meclisleri, kendi Devletlerinde köleliği ortadan kaldırmak için sorgusuz sualsiz yetkiye sahipti; ama şimdi Eyalet Anayasaları için bu gücü Yasama Meclislerinden alıkoymak oldukça moda hale geliyor. O günlerde, ortak rıza ile siyah adamın esaretinin yeni ülkelere yayılması yasaklandı ...

— Abraham Lincoln, Springfield, Illinois'de Konuşma, (26 Haziran 1857).[18]

Bu, köleliğin ahlaki doğasına ilişkin ideolojide, Missouri Uzlaşması 1820'de, birçok insanın köleliği 18. yüzyılın sonlarında yaptıkları gibi "büyük bir kötülük" olarak değil, 19. yüzyıl Güney Carolinian Demokrat'ın sözleriyle görmeye başladığı John C. Calhoun, bir "olumlu iyi". Bu değişimin bir sonucu olarak, kölelerin kurtuluşunu sınırlayan güney köle devletlerinde yasalar çıkarılmaya başlandı, bu, 18. yüzyılın sonlarında Amerikan Devrimi sırasında oldukça yaygın bir şeydi. Edward Coles ve Robert Carter kölelerini ilham kaynağı olarak sömürge devrimcilerin Amerikan Aydınlanma ilkelerini kullanarak özgürleştirdiler.[19] Abraham Lincoln, ideolojideki bu değişimi fark etti ve 1855 tarihli bir arkadaşına yazdığı mektupta şunları yazdı:

[...] Yozlaşmadaki ilerlememiz bana oldukça hızlı görünüyor. Millet olarak 'bütün insanlar eşit yaratılır' diyerek işe başladık. Şimdi pratik olarak 'zenciler dışında tüm insanlar eşit yaratılmıştır' okuyoruz. Know-Nothings kontrolü ele geçirdiğinde, "zenciler, yabancılar ve katolikler dışında tüm insanlar eşit yaratılmıştır" yazacaktır. Bu söz konusu olduğunda, özgürlüğü sevme iddiasında bulunmadıkları bir ülkeye göç etmeyi tercih etmeliyim - örneğin, despotizmin saf olabildiği ve ikiyüzlülüğün temel alaşımı olmadan Rusya'ya. [...]

— Abraham Lincoln, Joshua Speed'e mektup (24 Ağustos 1855).[20]

Bu fikir kayması güneylileri ve Demokratların kölelik kurumunu savunmadaki eylemlerini sertleştirdi ve nihayetinde Amerika Birleşik Devletleri'ndeki köleliği sonsuza dek sona erdirecek olan Amerikan İç Savaşı ile sonuçlandı.

1868 anayasası

1868 anayasası 15 Mayıs 1868'de kabul edildi ve bir yıl sonra 1 Aralık 1869'da devlet halkı tarafından onaylandı ve onaylandı. Bu, 22 yıl sonra yerini alan 1890 anayasasından farklıydı, çünkü bu anayasa tamamen oluşturuldu ve onaylandı. bir kongre ile.

22 yıldır kullanımda olan 1868 anayasası, devlet tarihinde halkın rızasıyla onaylanan ilk anayasaydı ve onaylanmaları için genel olarak halka gönderildi. Aynı zamanda Mississippi'nin hem Afrikalı Amerikalı hem de beyaz delegeler tarafından yaratılan ilk eyalet anayasasıydı.[8][17] 1868 anayasası, önceki iki eyalet anayasasına göre yasal olan köleliği yasakladı, vatandaşlık, oy kullanma ve silah taşıma hakkı siyah erkeklere, tarihinde ilk kez eyaletteki tüm çocuklar için devlet okulları kurdu, yasal işlemlerde çifte tehlikeyi yasakladı ve evli kadınların mülkiyet haklarını korudu.[8]

Buna rağmen, kuzey Demokrat Parti tarafından desteklenen güneyli Demokratlar, eğitim seviyelerine veya mesleki yeterliliklerine bakılmaksızın, siyah Mississippianslar için ve aslında genel olarak siyah güneyliler için her türlü temel sivil haklara şiddetle karşı çıktılar.[21] Ancak, ABD Ordusu'nun Mississippi'yi işgal etmesini engellediği gerekçesiyle 1868 anayasasının kabulüne razı oldular. şiddetli Demokratik devralma Devlet, bir Demokrat'ın yıl içinde ABD başkanlığına yükselmesinin ardından sona erecekti.[17] Ancak, Cumhuriyetçi aday olarak bu varsayım yanlış çıktı, Ulysses S. Grant, kazandı 1868 ABD başkanlık seçimi ve 1872.

Mississippi, 1870 Şubatında Amerika Birleşik Devletleri'ne tamamen geri kabul edildiğinde,[5] bunu 1870'te ABD Kongresi tarafından belirlenen ön koşulda yaptı Mississippi Eyaletini kabul etme kararıdevletin 1868 anayasasını, oy veren nüfusunun özgürleştirilmiş köleler gibi kesimlerini haklarından mahrum bırakmak amacıyla değiştirmemesi veya değiştirmemesi.[17] Ancak, sonunda bu anlaşma önemsenmedi. 1876'da Demokratlar Mississippi valiliğini kazandılar ve 14 yıl sonra, 1890'da, 1868 anayasası, kabul edildikten 22 yıl sonra ezici bir çoğunluğu beyaz Demokratlardan oluşan bir sözleşmeyle yeni bir anayasa ile değiştirildi. Bu, Mississippi Eyaleti'ndeki Afrikalı Amerikalı seçmenleri önümüzdeki seksen yıl boyunca fiilen haklarından mahrum etti.[16][22][23]

Hükümler

Savaş sonrası 1868 anayasasının ilk maddesi, Haklar Bildirgesi olarak da bilinen 1. maddeydi. Birleşik Devletler Haklar Bildirgesi'nden birçok ilkeyi ödünç alarak, eyaletin tüm sakinlerinin sahip olduğu hakları belirledi.

Önsöz

1868 anayasasının başlangıcında, anayasanın oluşturulması ve kabul edilmesinin amacı, "adalet", "kamu düzeni", "hak", "özgürlük" ve "özgürlüğün" kurulması ve sürdürülmesi olarak belirtiliyordu:

Adaletin tesis edilmesi, kamu düzeninin sürdürülmesi ve özgürlüğün sürdürülmesi için, biz, Mississippi Eyaleti halkı olarak, kendi hükümet biçimimizi seçme hakkının özgürce kullanılması için Yüce Tanrı'ya minnettarız, bu Anayasayı buyuruyoruz.

— Önsöz, Mississippi 1868 Anayasası (15 Mayıs 1868).

Bu, onun yerine geçen 1890 eyalet anayasasının lafzından farklıydı; burada "adalet", "kamu düzeni", "özgürlük", "hak" ve "özgürlük" ile ilgili tüm atıflar, başlangıçtan tamamen ve tamamen kaldırıldı. Kongre delegeleri tarafından. "Konvansiyonda toplandı" ifadesi, "Mississippi halkı" ndan sonra, anayasanın onaylanmak ve onaylanmak üzere devletin geneline gönderilmediğini temsil etmek için yer alırken, 1868 tarihli olanı şöyleydi:

Biz Mississippi halkı Konvansiyon ile Yüce Tanrı'ya minnettar olarak toplandık ve çalışmalarımızdaki kutsamasını çağırarak bu Anayasayı buyuruyor ve kuruyoruz.

— Önsöz, Mississippi 1890 Anayasası (1 Kasım 1890).

Vatandaşlık

Eyalet anayasasının Haklar Bildirgesi bölümünün ilk bölümü kimin devlet vatandaşı olduğunu belirledi. Bölüm, Mississippi Eyaleti sınırları içinde yaşayan "tüm kişilerin" vatandaşı olduğunu ilan etti. Bu, cinsiyet veya renklerine bakılmaksızın eyalette yaşayan tüm insanlara vatandaşlık kazandırdı:

Bu Eyalette ikamet eden tüm kişiler, Amerika Birleşik Devletleri vatandaşı, burada Mississippi Eyaleti vatandaşı ilan edilir.

— Bölüm 1, Madde 1, Mississippi 1868 Anayasası (15 Mayıs 1868)

Kölelik

Amerikan İç Savaşı'nda Konfederasyonun Birliğin eline geçmesiyle, Amerika Birleşik Devletleri'nde köleliği yasaklamak için On Üçüncü Değişiklik onaylandı. Sonuç olarak, Mississippi'nin 1868 anayasası, eyaletin tüm eyalette köleliği yasaklayan ilk anayasasıydı:

Tarafın usulüne uygun olarak mahkum edilmiş olduğu suçun cezası dışında, bu Devlette ne kölelik ne de gönülsüz kulluk olmayacaktır.

— Bölüm 19, Madde 1, Mississippi 1868 Anayasası (15 Mayıs 1868).

1890 anayasası

Mississippi'nin mevcut anayasası, 1 Kasım 1890'da kabul edildi ve 1868 anayasasının yerini aldı. Amerikan İç Savaşı yeni serbest bırakılan kölelere özgürlükler ve medeni haklar vermek.[8][17]

Arka fon

Sonunun ardından Amerikan İç Savaşı 1865'te Mississippian seçimleri, beyaz üstünlükçü terör örgütleri gibi ölümcül şiddet ve seçmen sindirilmesiyle yapıldı. "Kırmızı Gömlekler "Siyah seçmenlerin ve Demokratlara muhalefet eden beyaz müttefiklerinin Cumhuriyetçiler adına oy kullanmasını önlemek için silahlı güç ve şiddetli terörizm kullandı. Birçok Cumhuriyetçi, siyah Mississippi ve bunların beyaz müttefikleri, örneğin Matthews Yazdır,[25] sonuç olarak silahlı Demokrat paramiliter güçler tarafından linç edilip öldürüldü.[22][23][25]

Kölelik, On Üçüncü Değişiklik ile yasal olarak sona erdirilmiş olsa da, Konfederasyonların ve Demokratların bunu meşrulaştırmak için kullandıkları ideoloji, artık serbest bırakılan köleleri ve Afrikalı Amerikalıların temel sivil hak ve özgürlüklerini inkar etmek için gerekçe olarak kullanılıyor. . Eski kölelik karşıtı olarak Frederick Douglass Aralık 1869'da Boston, Massachusetts'te yapılan bir konuşmada:

[...] Geç isyana önderlik eden Güneyli beyefendiler, bu noktada inançlarından hiçbir şekilde ayrılmadılar. Zencilerden bağımsız olmak istiyorlar. Köleliğe inanıyorlardı ve buna hala inanıyorlar. Aristokrat bir sınıfa inanıyorlardı ve buna hala inanıyorlarve böyle bir sınıf için temel unsurlardan biri olan köleliği kaybetmiş olsalar da, o sınıfın yeniden inşası için hala iki önemli koşula sahipler. Zekaları ve toprakları var. Bunlardan arazi daha önemlidir. Değerli bir batıl inancın tüm azimiyle ona tutunuyorlar. Ne zenciye satacaklar, ne de halıcıya huzur içinde vermeyecekler, ama onu kendileri ve çocukları için sonsuza kadar tutmaya kararlılar. Henüz bir ilke gittiğinde olayın da gitmesi gerektiğini öğrenmemişlerdir; kölelik altında bilge ve uygun olanın, genel bir özgürlük durumunda aptalca ve yaramaz olduğunu; yeni şarap geldiğinde eski şişelerin değersiz olduğunu; ancak toprağın, işleyecek elin olmadığı şüpheli bir fayda olduğunu keşfettiler. [...]

— Frederick Douglass, Bizim Bileşik Milliyetimiz, (7 Aralık 1869), vurgular eklenmiştir, Boston, Massachusetts.[26]

Amerikan İç Savaşı'nı izleyen yıllarda, ABD Ordusu güçleri, Afrika kökenli Amerikalıların ve serbest bırakılan kölelerin yaşamlarını ve haklarını koruyan, yeniden kabul edilen ABD'nin güney eyaletlerinde konuşlandırıldı. Demokratlar, ABD ordusunun orada bulunmasına şiddetle karşı çıktılar, çünkü söz konusu devletlerin Demokratların şiddetli bir şekilde ele geçirilmesini engelledi. Ancak, her zaman her yerde bulunabilecek yeterli ordu askeri yoktu ve bu nedenle, seçmen kayıtlarını adil ve tarafsız olacak şekilde denetleyebilseler de, sicil kaydı için seçmen kayıt bürosuna gidip gelirken serbest bırakılanları koruyamadılar ve bu nedenle birçok serbest bırakılan kişi linç edildi. Özgür insanlara yönelik şiddet artarken, 1875 Medeni Haklar Yasası Cumhuriyetçi ABD başkanı tarafından yasa ile imzalandı Ulysses S. Grant onları korumak için. Bununla birlikte, ABD Yüksek Mahkemesi 1883'te anayasaya aykırı karar verdiği için bu yasa kısa ömürlü olacaktır.

Ağustos 1877'de eski ABD başkanı Ulysses S. Grant Birkaç ay önce görevden ayrılmış ve dünya turuna çıkmış olan, Londra'dan ABD Donanması subayına bir mektup yazdı. Daniel Ammen sonra 1877 Uzlaşması Demokratların, işçi grevlerini bastırmak için ezici bir askeri güç kullanmaya sözlü desteklerindeki çelişkiler hakkında, ancak Afro-Amerikan seçmenlerin haklarının ihlal edilmesini savunmak için kullanıldığında itiraz ediyorlar. ABD hükümetinin, rengine bakılmaksızın tüm vatandaşlarının haklarını ihlal edilmekten koruması gerektiğini belirtti:

[...] Görev sürem boyunca tüm Demokrat basın ve Cumhuriyetçi basının morbid derecede dürüst ve 'iyileştirici' kısmı, ABD birliklerini Güney Eyaletler'de konuşlandırmanın korkunç olduğunu düşündü ve çağrıldıklarında zencilerin hayatlarını korumak -Anayasa'ya göre tenleri beyaz gibi vatandaşlar-Ülke, birkaç yıl boyunca körükledikleri öfke sesini taşıyacak kadar büyük değildi. Ancak şimdi, tehlikenin tehdit ettiği en ufak bir intimasyona yönelik bir grevi bastırmak için hükümetin tüm gücünü tüketmek konusunda hiçbir tereddüt yok. Tüm taraflar bunun doğru olduğu konusunda hemfikirdir, ben de öyle. Güney Carolina, Mississippi veya Louisiana'da bir zenci ayaklanması çıkarsa veya bu eyaletlerden herhangi birinde büyük çoğunlukta olan zenciler beyazlara gözdağı verirse sandık başına gitmekten ya da Amerikan vatandaşlarının herhangi bir hakkını kullanmaktan, başkanın görevine ilişkin bir duygu paylaşımı olmayacaktı. Öyle görünüyor kural her iki yönde de çalışmalıdır. [...]

— Ulysses S. Grant, Commodore Daniel Ammen'e mektup (26 Ağustos 1877), vurgu eklendi. Bristol Hotel, Burlington Gardens, Londra, Birleşik Krallık.[27]

Yıllarca süren terörizm ve paramiliter şiddetin ardından 1890'a gelindiğinde, Afrikalı Amerikalılar "Güney siyasetinin arenasından büyük ölçüde kayboldular".[28] Demokratlar vardı tartışmalı kontrol Mississippi eyaleti hükümetinin Cumhuriyetçi Parti Devletin son 19. yüzyıl Cumhuriyetçi valisi ile etkisi, Adelbert Ames, düşman bir yasama organının görevden alma tehditleri nedeniyle 1876'da görevden istifa etti. Geçen yıl, Kasım 1875'te, teröristler ve Demokratlar, silahlı şiddet kullanarak hileli bir seçimde birçok siyahi ve Cumhuriyetçi seçmeni eyalet sandıklarına gitmekten zorla alıkoymuşlardı.[29] Bu, Demokratların Mississippian eyalet yasama organının kontrolünü ele geçirmesiyle sonuçlandı.

Yükselişi ile Rutherford B. Hayes ABD başkanlığına ve müteakip 1877 Uzlaşması ABD kabinesine güneyli bir Demokrat atandı ve ABD Ordusu kuvvetleri halktan çekilerek üslerine kapatıldı ve 1879'da 1,155 asker bırakıldı. Bu, Demokratların söz konusu devletleri şiddetle ele geçirmesini ve Afrikalı Amerikalıların haklarından mahrum etmesini önleyen son engeli de etkili bir şekilde kaldırdı seçmenler ve eski Konfederasyon eyaletlerinde Cumhuriyetçi Parti'nin yaklaşık bir yüzyıl boyunca etkili bir şekilde sona erdiğini belirledi.

Şu anda çoğunlukla Demokratlar tarafından kontrol edilen Mississippi eyalet hükümeti, devletin siyah oy kullanan nüfusunu haklarından mahrum etmek için tasarlanan terörist şiddet kampanyalarını, bunu yapmak için başka yöntemler kullanarak sona erdirmeye karar verdi. Ancak Demokratlar, siyah seçmenleri ve onların beyaz müttefiklerini haklarından mahrum etmek için yalnızca terörizmi kullanmak yerine, bunu yapmalarına izin verecek eyalet anayasalarının hükümlerini benimseyerek bunu yapmak için kanunu kullanmaya karar verdiler. Gözlerini, hem kuzeyli hem de güneyli Demokratların şiddetle karşı çıktığı siyah vatandaşlara özgürlük, vatandaşlık, oy hakkı ve diğer insan haklarını yasal olarak garanti eden 1868 Mississippi anayasasını değiştirmeye diktiler.[21][22][23]

Yaratma ve benimseme

Mississippi'nin 1890 eyalet anayasası, 1 Kasım 1890'da kabul edildikten sonra orijinal olarak on dört madde içeren, eyalet hükümetinin yetkilerini genişletti ve 1868 anayasasından daha uzundu, sadece on üç maddeye sahipti.

Anayasal Kongre

5 Şubat 1890'da Demokratların çoğunlukta olduğu Mississippi yasama organı, 1868 anayasasının yerini alacak bir kongre çağrısı yapmak için oy kullandı. 11 Mart 1890'da Mississippi'nin Demokratik valisi, John M. Stone, Ağustos ayında başlayacak anayasa konvansiyonuna katılacak delegelerin seçilmesi için 29 Temmuz'da bir seçim yapılacağını açıkladı. Bununla birlikte, eyalet hükümeti bu noktada Demokratlar tarafından sağlam bir şekilde kontrol edildiğinden, delege seçiminin sonucu, anayasa konvansiyonunun seçilen 134 delegesinin oldu, 133 beyazdı ve devlete sahip olmasına rağmen yalnızca biri Afrika kökenli Amerikalıydı. Afrikalı Amerikalıların çoğunluğu yüzde 58.[1][30]

Jackson'da gerçekleşen ve 12 Ağustos 1890'da başlayan kongre sırasında,[1] 1 Kasım'a kadar, sele meyilli bölgelerde setlerin inşasından çeşitli konular tartışıldı. Mississippi Deltası demiryolları düzenlemelerine. Bununla birlikte, en önemli mesele, gerçekten de, sözleşmenin neden ilk başta çağrıldığının ana nedeni, katalizörü ve gerekçesi, "okuryazarlık testleri " ve "Anket Vergileri "Oylama için önkoşul olarak, amaçlanan öznel uygulama onlarca yıl boyunca eyaletteki neredeyse her Afrikalı Amerikalıyı haklarından mahrum bırakacaktı. Bu, 1868 anayasasına göre mevcut olmayan bir şeydi. Testleri zorunlu kılan ifadeler, görünüşte bunların olması gerektiğini ima etse de Tüm insanlara eşit olarak uygulandığında, sözleşme, Afrikalı Amerikalı seçmenlerin oy kullanmasını önlemek için bu okuryazarlık testlerini ve anket vergilerini sübjektif olarak uygulamak istedi. Bazıları eski Konfederasyonlardan olan sözleşmenin delegelerine göre, Siyahların oy hakkı "uygarlığı yıkma çabasıydı" ".[31]

Nitekim 1890 anayasa kongresi başkanı Solomon Saladin'e göre "S.S." Calhoon,[3][4] bir yargıç Hinds İlçe Sözleşme, özellikle eyaletin Afrikalı Amerikalı seçmenlerini haklarından mahrum etmek, haklarını kısıtlamak ve onları toplumun geri kalanından izole etmek ve ayırmak için çağrıldı. Bunu yapmayan bir anayasanın kongre üyeleri için kabul edilemez olduğunu açıkça belirtti:

[...] Evrenin dibinde patlarsa gerçeği söyleyelim. [...] Zencileri dışlamak için buraya geldik. Bundan başka hiçbir şey cevap vermeyecek.

Başka bir delege, bir Bolivar İlçesi George P. Melchior adındaki ekici, bu görüşü şu sözlerle yineledi:

[...] Bu bu Sözleşmenin açık niyeti Mississippi Eyaletine, 'beyaz üstünlüğü' güvence altına almak için. [...]

— Bolivar İlçesinden Temsilci George P. Melchior, Mississippi 1890 Anayasa Sözleşmesi (D-MS), vurgu eklendi.

Bir temsilci, bir avukat Adams County Will T. Martin adlı[33] kongre üyelerinin bu düşünce zincirine devam ederek şunları söyledi:

[...] korumak için değilse neden buradasınız beyaz üstünlük? [...]

— Adams County Temsilcisi Will T. Martin, Mississippi 1890 Anayasa Sözleşmesi (D-MS), vurgu eklendi.[33]

Mississippi'deki beyaz Demokratların ve diğer güney ABD eyaletlerindeki Demokratların siyah oy kullanan nüfuslarını haklarından mahrum bırakma arzusunun ardındaki birincil mantık, Cumhuriyetçi adaylara ezici bir şekilde oy vermeleri ve onları göreve getirmeleriydi ki bu, Demokratların aşağılayıcı bir şekilde şu şekilde bahsettiği bir sonuçtu: "zenci egemenliği tehdidi" veya "zenci üstünlüğü".[34][35] O dönemde Demokratların ülke genelindeki resmi politikası ataerkil beyaz üstünlüğünü, parti sloganları olarak "Burası Beyaz Adamın Ülkesi: Beyaz Adam Kuralı Olsun!" ve "Bu bir Beyaz Adamın Hükümeti!"[36][37] Bir Güney Carolinalı siyasetçinin 1909'da söylediği gibi, Demokrat Parti "bir tahta ve yalnızca bir tahta için vardı, yani burası beyaz bir adamın ülkesi ve onu beyaz adamlar yönetmeli".[38] Hatta kendisine "Beyaz Adamın Partisi" deniyordu.[39]

Mississippi'nin o sırada eyaletin toplam nüfusunun yaklaşık yüzde 58'ini oluşturan büyük Afro-Amerikan nüfusu nedeniyle,[1] Beyaz üstünlükçü teröristlerin ve Demokrat destekli paramiliterlerin dış müdahalesi olmaksızın özgür ve adil olsalar ve çoğu seçimde pek çok Cumhuriyetçi aday göreve gelirdi. Demokratların, siyah Mississippi'lileri oy hakkından mahrum etme ve marjinalleştirme arzusunun ikinci nedeni, Demokratların hor gördükleri ve alçakgönüllülükle tuttukları Afrikalı Amerikalılara karşı sahip oldukları şiddetli bağnazlık ve önyargıların derin ideolojisiydi. Demokratlar, Afrikalı Amerikalılarla ilgili bağnaz görüşlerini, sözde bilimsel ırkçılık[3] ve bir itibarını yitirmiş alternatif yanlış yorumlama Hıristiyan kutsal incil.

Kongre sırasında bir delege, A.J. Paxton, suggested adding a clause into the new state constitution that African Americans be explicitly forbidden from holding office in the state at all, by adding into the constitution a clause stating that "No negro, or person having as much as one-eighth negro blood, shall hold office in this State." However, since this would have been a blatant and overt violation of the United States Constitution, it was not included in the final draft. The convention decided to use more subtly-worded methods to effectively obtain that result.[40]

Another delegate, T.V. Noland, a lawyer from Wilkinson County, suggested introducing into the constitution a clause forbidding marriages between a "white or Caucasian" person with a person of that of the "Negro or Mongolian race". He stated that they add into the constitution that "the intermarriage of a person of the white or Caucasian race, with a person of the negro or Mongolian race, is prohibited in this State." A slightly modified version of this proposed clause was included into the completed constitution, with "Mongolian race" being replaced with that of a person having "one-eighth or more of negro blood".[41]

In an 1896 ruling, the Mississippi Supreme Court, of which the 1890 convention's president later became a member, delivered a legal opinion regarding the justification and reasoning the Democrats had used for the adoption of the 1890 constitution in Ratliff v. Beale, and how it came to be. The court stated that the purpose of the 1890 convention was to "obstruct the exercise of the franchise by the negro race". In the comments, the court admitted that the provisions of the Mississippian state constitution had violated the United States Constitution, but did not order that they be removed or modified. Instead, the court praised the 1890 constitution, saying that it was morally and legally justified and necessary due to the "peculiarities" that all African Americans allegedly held, which it went on to describe. The court stated that African Americans were "criminal members" who were prone to committing "furitive offenses" and thus, should not be allowed to vote in the state. The court also praised the terrorist violence that resulted in the Democrats taking control of the state, saying it justified and necessary because the Democrat members of "the white race" were "superior in spirit, in governmental instinct, and in intelligence":

[...] This was succeeded by a semimilitary, semicivil uprising, under which the white race, inferior in number, but superior in spirit, in governmental instinct, and in intelligence, was restored to power. [...] The federal constitution prohibited the adoption of any laws under which a discrimination should be made by reason of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. [...] Within the field of permissible action under the limitations imposed by the federal constitution, the convention swept the circle of expedients to obstruct the exercise of the franchise by the negro race. By reason of its previous condition of servitude and dependence, this race had acquired or accentuated certain peculiarities of habit, of temperament, and of character, which clearly distinguished it as a race from that of the whites,-a patient, docile people, but careless, landless, and migratory within narrow limits, without forethought, and its criminal members given rather to furtive offenses than to the robust crimes of the whites. Restrained by the federal constitution from discriminating against the negro race, the convention discriminated against its characteristics and the offenses to which its weaker members were prone. [...] But it must be remembered that our constitution was never submitted to the people. It was put in operation by the body which framed it, and therefore the question is what that body meant by the language used. [...] In our opinion, the clause was primarily intended by the framers of the constitution as a clog upon the franchise, and secondarily and incidentally only as a means of revenue.

Due to their profound bigotry and prejudice, Mississippian Democrats viewed the concept of African Americans, whom they considered to be profoundly ignorant and immoral and incapable of improvement, voting, as being detrimental to their party's interests and the well-being of the state.[43] In addition, the Democrats did not want to adjust their policies to better suit the interests of the state's African American constituents, nor did they desire to abandon their bigoted views and see them treated with dignity and respect on an equal footing. As a result, total and massive African American disenfranchisement was the only option that the state's Democrats saw as being preferable to their party's interests.[6]

As J.B. Chrisman, a Mississippian judge from Lincoln County, remarked, in salutatory praise of the 1890 constitution, marginalizing and disenfranchising African Americans was seen as a kind of social badge of honor for southern Democratic men:

Tanrım! Tanrım! Is there to be no higher ambition for the young white men of the south than that of keeping the Negro down?

— J.B. Chrisman, (emphasis added)[32]

The State of Mississippi was not alone at the time for creating adopting entirely new constitutions specifically for the purpose of disenfranchising and marginalizing African American voters. Other southern U.S. states, such as Güney Carolina, under its Democratic Vali Benjamin Ryan Tillman, created and adopted a new state constitution in 1895, five years after Mississippi did the same. As with Mississippi's 1890 constitution, the South Carolinian constitution of 1895 is still in effect today.[11] Oklahoma, which was not a state until 1907 but where slavery had been practiced before the Thirteenth amendment, adopted similar laws upon statehood.

Temsilci kompozisyon

The convention that created the 1890 constitution consisted of 134 men, of which, 133 were white delegates.[1] There was only 1 black delegate in the entire convention.[1] This was in stark contrast with the state population of Mississippi, which consisted of nearly 58 percent African American residents.[1]

- Convention president

The convention's president was Solomon Saladin "S.S." Calhoon,[3][4] a Mississippian judge from Hinds County who was a member of the state's supreme court.[3] Born in January 1838, Calhoon had been a newspaper editor before the Amerikan İç Savaşı başladı. When the war broke out over the expansion of slavery into western U.S. territories, Calhoon joined the Konfederasyon ordusu and ultimately became a lieutenant colonel.[3] Like most former Confederates and Democrats at the time, Calhoon was a fervent believer in patriarchal white supremacy and was vehemently opposed to any basic civil rights for African Americans. In 1890, Calhoon wrote a pamphlet entitled Negro Suffrage, where he outlined his opinions regarding African American voting in the state.[3] Regarding African Americans, Calhoon stated his conviction that they had:

[...] no advancement, no invention, no history, no literature, no governmental polity. We see only ignorance, slavery, cannibalism, no respective, cannibalism, no respect for women, no respect for anything [...] not inventive, not progressive, not resourceful, not energetic [...]

Regarding African Americans voting in elections, Calhoon stated his firm opinion that:

[...] Negro suffrage is an evil, and an evil [...]

During the convention, Calhoon reiterated the views he had written in his pamphlet in an oratory delivered to the convention's members, saying that allowing African Americans to vote would lead to the "ruin" of the state, for they were allegedly "unfit to rule":

[...] The negro race seems unable to maintain even its own imitative acquirements. It seems unfit to rule. Its rule seems to mean, as it has always meant, stagnation, the enslavement of woman, the brutilization of man, animal savagery, universal ruin. [...]

Due to his prominent judicial position on the state's supreme court, any judicial challenges to the 1890 constitution that could have been brought forth to the court would have been rejected by him. Calhoon died in November 1908.[3][4]

- Cumhuriyetçiler

The convention consisted overwhelmingly of white Democrats, who were determined in their efforts to restrict and infringe upon the rights of black Mississippians. Marsh Cook, a white Republican from Jasper County who supported African American voting, attempted to join the convention, despite receiving death threats for attempting to do so. For supporting the right of black Mississippian citizens to vote in the state's elections, Cook was lynched and killed on a remote rural road, a common fate for many who were opposed to the Democrats at the time.[22][23]

- Afrika kökenli Amerikalılar

The only black member of the 1890 constitutional convention was a man from Höyük Bayou isimli Isaiah Montgomery, whom white Democrats allowed into the convention because he was willing to support their desires of total African American voter disenfranchisement. Montgomery, who had been a former slave of Confederate president Jefferson Davis ' brother, delivered a speech at the convention advocating black disenfranchisement, to the approval of the Democrats, but much to the outrage of his black peers, who labelled him a "traitor" and likened him to Judas Iscariot.[22][23][44]

Hükümler

Oy hakkından mahrum bırakma

The 1890 convention considered the portions of its new constitution that instituted okuryazarlık testleri ve Anket Vergileri as being the most important. Indeed, the implementation of these measures was the reason for the convention's very existence.[6]

The portion of the 1890 constitution that would specifically allow the state to prevent black voters from casting ballots was Article 12's Section 244, which required that after January 1, 1892, any potential voter prove that they were literate. One method to determine their literacy was for the voter to describe, to a registrar, a "reasonable interpretation" of the state constitution.[16] This was one form of the state's okuryazarlık testleri, in which the constitution mandated that voters be "literate". Sample questions to determine "literacy" were made intentionally and overtly confusing and vague when applied to African Americans, such as questions inquiring as to the exact number of bubbles in a bar of soap.[17]

The exact wording of Article 12's Section 244, from its enactment in November 1890 to its repeal in December 1975, was as follows:

On and after the first day of January, A. D., 1892, every elector shall, in addition to the foregoing qualifications, be able to read any section of the constitution of this State; or he shall be able to understand the same when read to him, or give a reasonable interpretation thereof. A new registration shall be made before the next ensuing election after January the first, A.D., 1892.

— Section 244, Article 12, Mississippi Constitution of 1890, (November 1, 1890)

Although the wording of the 1890 constitution itself regarding voting was not explicitly discriminatory, the desired intent of the 1890 constitution's framers was that a state registrar, who would be white and politically appointed by Democrats, would deny any potential African American voter from being enrolled by rejecting their answers to a okuryazarlık testi as erroneous, regardless of whether or not it actually was.[16] The 1890 constitution also imposed a two dollar poll tax for male voters, to take effect after January 1, 1892.[45]

After legal challenges to these laws survived U.S. judicial review, such as in 1898's Williams / Mississippi, thanks to their race-neutral language, other southern U.S. states, such as Güney Carolina 1895'te[11] ve Oklahoma by 1907,[16] emulated this method to disenfranchise their black voter base, known as "The Mississippi Plan ",[16] in which a law's seemingly un-discriminatory and vague wording would be applied in an arbitrary, subjective, and discriminatory manner by the authorities charged with enforcing them.[16]

Despite the 1890 constitution's seemingly un-discriminatory wording on the surface on the subject of voting, Mississippian governor James K. Vardaman, a staunch Demokrat, boasted about its enabling of the state government to implement the disenfranchising of black voters. He unabashedly stated that the 1890 constitution's framers had created the constitution precisely to disenfranchise black voters, having desired to prevent black voters from casting ballots, not for any shortcomings they may or may not have had as voters, but for simply being black:

There is no use to equivocate or lie about the matter. [...] Mississippi's constitutional convention of 1890 was held for no other purpose than to eliminate the nigger from politics. Not the 'ignorant and vicious', as some of the apologists would have you believe, but the nigger. [...] Let the world know it just as it is.

Clarion-Defter gazete Jackson reiterated the views of Governor Vardaman and the 1890 convention, stating that:

They do not object to negroes voting on account of ignorance, but on account of color.

— Clarion-Defter, (emphasis added)[46]

In a veiled threat,[12] Governor Vardaman stated that were the 1890 constitution fail in its explicit intent to disenfranchise the state's African American voters, the state would utilize other methods to disenfranchise them:

In Mississippi we have in our constitution legislated against the racial peculiarities of the Negro. [...] When that device fails, we will resort to something else.

Governor Vardaman, like most southern Democrats at the time, was an outspoken proponent of using lynchings and terrorism as methods to marginalize and deter African American voters:

If it is necessary every Negro in the state will be lynched; it will be done to maintain white supremacy.

— James K. Vardaman, (emphasis added)[12]

Clarion-Defter newspaper, known for its vocal partisan support of the state's Democrats, also delivered a justification and rationale for the 1890 constitution's disenfranchising of black voters, expressing the white supremacist view that the framers of the 1890 constitution held, that even the most ignorant and uneducated white voter was preferable to the most well-educated and intelligent black voter:

If every negro in Mississippi was a class graduate of Harvard, and had been elected class orator [...] he would not be as well fitted to exercise the rights of suffrage as the Anglo-Saxon farm laborer.

— Clarion-Defter, (emphasis added)[47]

The effects of the new constitution were profound. In 1890, there were 70,000 more African American voters in Mississippi than there were white ones. By 1892, that number had dropped to 8,615 black voters out of 76,742 eligible voters.[48]

Sonra birinci Dünya Savaşı, Sidney D. Redmond, a black lawyer from Jackson and the chairman of the Mississippian Republican Party, attempted to investigate the disenfranchising of black voters in Mississippi. He wrote letters of inquiry to several Mississippian counties, which went unanswered. He then inquired via telephone, and many of the counties responded to his inquiries by telling him that they did not "allow niggers to register" to vote.[47]

Several decades later, following an investigation by the United States government into the discriminatory voting practices of southern U.S. states,[1] the U.S. Supreme Court would declare that methods employed by state governments to disenfranchise African American voters and prevent them from casting ballots were direct violations of the precepts United States Constitution. As a result, Section 244 was rendered effectively null and void under the rulings of U.S. court decisions such as Harper v. Virginia and the section was formally repealed by the state on December 8, 1975, 85 years after it was created.

Silah kontrolü

In addition to disenfranchising black voters, the 1890 constitutional convention placed into the state constitution, for the first time, the explicit ability of the state government to explicitly restrict the right of people to bear arms across the state. It did this in Article 3's Section 12, by shifting the right of bearing arms from the broad definition of "all persons" to the more restrictive term of "citizen" only,[13][14][15] who were intended to be limited to white men only by the 1890 constitution's framers. By granting to the state government the power to enact laws restricting the carrying of concealed weapons by the state's residents, it gave the state a newly enumerated power it did not have under the state's three previous constitutions.[13][14][15]

During the late 19th century and well into the early 20th century, there was a growing trend among the governments of southern U.S. states, controlled by Democrats, in implementing stricter and more stringent regulations restrictions on the right of firearms ownership. This was done in order to prevent African Americans from being able to bear arms for the purpose of defending themselves against the ever-growing threat of lynchings, terrorism, and extrajudicial paramilitary violence at the hands of Democrats and white supremacists, designed to prevent black voters from electing Republicans. Mississippi was no stranger to such restrictive laws; an 1817 law even forbade an African American person from being in possession of a canine.[13][14][15] As with the sections of the 1890 constitution that disenfranchised black voters, the laws regarding weapons ownership used ostensibly non-discriminatory wording, but were enforced by the state government in an arbitrarily and subjective discriminatory manner, as in many southern U.S. states at the time.[13][14][15]

Regarding the right to bear arms, the 1890 constitution marked a departure from the spirit of the 1868 constitution, and indeed, from the 1817 and 1832 ones as well, all of which granted the people, rather than citizens, of the state the right to bear arms for self-defense and did not explicitly grant the state government the power to regulate said ownership.[8] The 1890 law's wording further restricted the right to bear arms to the "citizen" for "his" defense, rather than the 1868 constitution's general-neutral "all persons".[8]

The differences between the 1868 and 1890 constitutions regarding the right of the state's people to bear arms are as follows:

All persons shall have a right to keep and bear arms for their defence.

— Section 15, Article 1, Mississippi Constitution of 1868, (emphasis added).[8]

The right of every vatandaş to keep and bear arms in defense of his home, person, or property, or in aid of the civil power when thereto legally summoned, shall not be called in question, but the legislature may regulate or forbid carrying concealed weapons.

— Section 12, Article 3, Mississippi Constitution of 1890, (emphasis added)

Unlike other sections of the 1890 constitution that would later be repealed or modified by the state, such as the sections regarding marriages, education, and prisons, Article 3's Section 12 has remained unchanged, with the wording being exactly the same as it was in 1890, as Article 15's Section 273 prohibit the modification or repeal any of the sections contained in Article 3. To do so, an entirely new constitution would have to be created and adopted by the state.

Marriage restrictions

Öncesinde Amerikan İç Savaşı, laws in southern slave states, and even in some in northern free states, prohibited marriages between African Americans and those who were not, to assist in the solidification of the institution of slavery by discouraging contact between the two groups. However, after the Union defeated the Confederacy in 1865 and abolished slavery in the U.S., these laws were removed in the former Confederate slave states when they adopted new constitutions, which Mississippi did in 1868. However, Democrats, who objected fervently to any marriages between African Americans and those who were not, reinstated these laws when they violently took control of the states from Republicans in the 1880s and 1890s, instituting Jim Crow and segregation kısa süre sonra. These laws then lasted for decades, being declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1967, though they remained codified in law until they were formally removed in the late 20th century.

Unlike the outgoing 1868 constitution, which contained no such restriction or prohibition, the 1890 constitution criminalized, across the state, the marriage of a "white person" to a "negro", "mulatto", or any person who had "one-eighth or more of negro blood" and mandated that the state refuse to recognize such marriages:

The marriage of a white person with a negro or mulatto, or person who shall have one-eighth or more of negro blood, shall be unlawful and void.

— Section 263, Mississippi Constitution of 1890, (November 1, 1890)

In 1967, after nearly 77 years of the law being in effect, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Loving / Virginia that laws such as the Mississippian state constitution's Section 263 violated the Amerika Birleşik Devletleri Anayasası 's On dördüncü Değişiklik. Thus, the law became legally unenforceable after 1967. However, it took until December 4, 1987, 20 years after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional, for the section to be formally repealed from the state's constitution. Other U.S. states with similar laws, such as Güney Carolina ve Alabama, took until 1998 and 2000 to formally repeal them from their state constitutions, which was done in popular referendums that passed with slim majorities.[49]

Segregated prisons

Unlike the 1868 constitution, which did not grant the state the power to do so, the 1890 constitution explicitly granted to the state government, in Section 225, the power to separate "white" and "black" convicts "as far as practicable":

[...] It may provide for the commutation of the sentence of convicts for good behavior, and for the constant separation of the sexes, and for the separation of the white and black convicts as far as practicable, and for religious worship for the convicts.

— Section 225, Mississippi Constitution of 1890, (emphasis added)

The wording granting the state the power to implement the "separation of the white and black convicts as far as practicable" would later be repealed, although the section prescribing the "constant separation of the sexes" is still in effect.

Segregated schools

Unlike the 1868 constitution, which contained no such requirement, the 1890 constitution introduced for the first time and mandated, in Section 207, that "children of the white and colored races" attend separate schools. Unlike Section 225, which merely granted the state the ability to segregate "white and black convicts", Section 207, created on October 7, 1890,[50] specifically mandated that schools be segregated between "the white and colored races":

Separate schools shall be maintained for children of the white and colored races.

— Section 207, Article 8, Mississippi Constitution of 1890, (November 1, 1890)

The result of the establishment of separate schools for students of "the white and colored races", which did not exist under the 1868 constitution, was that students of the latter race were forced to attend schools that were, in almost every instance, deliberately of substandard quality when compared to the schools attended by white students:

The only effect of Negro education is to spoil a good field hand and make an insolent cook.

— James K. Vardaman, emphasis added, Governor of Mississippi (D-MS)[43]

This patriarchal white supremacist view held by the Democrats, who sought to limit educational and economic opportunities for African Americans, differed greatly from the views of that of the Republicans in the 1870s and 1880s, who believed that African Americans should be allowed to vote, own land and property, attend high-quality schools, and own firearms, believing that doing so was morally right and would improve the strength and well-being of the country:

We have got to choose between two results. With these four millions of Negroes, either you must have four millions of disfranchised, disarmed, untaught, landless, thriftless, non-producing, non-consuming, degraded men, or else you must have four millions of land-holding, industrious, arms-bearing, and voting population. Choose between the two! Which will you have?

— Richard Henry Dana, Jr., (emphasis added)[51]

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Brown v. Eğitim Kurulu that laws such as Section 207 violated the United States Constitution, and as such, the law became legally unenforceable. However, it took until December 22, 1978 for the section to be modified to not violate the U.S. Constitution, 24 years after the ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court that deemed it illegal. During this period, Mississippi's politicians considered altering the constitution to abolish public schools entirely,[52] and, amongst some politicians, to give white and negro children funds to attend separate private schools.[53] However, the fact that Mississippi lacked the tradition of private schools present in the Kuzeydoğu ve Ortabatı[54] made them feel this was impractical.

Gelecek

While the Mississippian state constitution that was adopted in 1890 is still in effect today, many of its original tenets and sections have since been modified or repealed; most of these were in response to U.S. Supreme Court rulings such as Harper v. Virginia, that declared most of these sections to have violated the United States Constitution.

In the decades since its adoption, several Mississippian governors have advocated replacing the constitution, however, despite heated debates in the legislature in the 1930s and 1950s, such attempts to replace the constitution have so far proved unsuccessful.[17]

Mississippian politician Gilbert E. Carmichael, a Cumhuriyetçi, has opined on moral and economic grounds that Mississippi adopt a new state constitution to replace the 1890 one, stating that it was detrimental to the success of business and commerce, and it represented an age of immoral bigotry and hatred.[17]

İçindekiler

The organization of the current Mississippi Constitution is laid out in a Preamble and 15 Articles. Each Article is subdivided into Sections. However, the Section numbering does not restart between Articles; Sections 1 and 2 are in Article 1 while Article 2 began with Section 3 (since repealed). As such, newly added Sections are given alpha characters after the number (such as Section 26A in Article 3)

Önsöz

We, the people of Mississippi in convention assembled, grateful to Almighty God, and involving his blessing on our work, do ordain and establish this Constitution.

Article 1: Distribution of Powers

Article 1 defines the separation of powers into legislative, executive, and judicial.

Article 2: Boundaries of the State

Article 2 formerly defined the state boundaries; after the 1990 repeal of section 3, the legislature holds the power to define the state boundaries.

Article 3: Bill of Rights

Most of the rights defined in Article 3 are identical to the rights to those that are found in the Amerika Birleşik Devletleri Haklar Bildirgesi.

Unique additions to the 1890 Mississippian constitution include Section 7 (denying the state the ability to ayrılmak from the United States, carried over from the 1868 constitution), Section 12 (explicitly permitting regulation of gizli taşıma weapons, which was not included in the 1868 constitution) and Sections 26, 26A, and 29 (on conditions for grand jury and bail necessitated by the Uyuşturucuyla Savaş ).

Section 12 allows for the ownership of weapons by the state's residents, however, the state government is given the power to regulate and abridge the carrying of concealed weapons. This differs from the 1868 constitution, which did not explicitly grant the state the power to restrict that right. Bölüm şunları belirtir:

The right of every citizen to keep and bear arms in defense of his home, person, or property, or in aid of the civil power when thereto legally summoned, shall not be called in question, but the legislature may regulate or forbid carrying concealed weapons.

Section 15, carried over verbatim from the 1868 constitution, forbids slavery or involuntary servitude within the state, except when done as a punishment for a crime:

There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in this state, otherwise than in the punishment of crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.

— Bölüm 15

Section 18 discusses freedom of religion. It prohibits religious tests as a qualification for officeholders. It also contains a unique clause which states that this right shall not be construed as to exclude the use of the "kutsal incil " from any public school:

No religious test as a qualification for office shall be required; and no preference shall be given by law to any religious sect or mode of worship; but the free enjoyment of all religious sentiments and the different modes of worship shall be held sacred. The rights hereby secured shall not be construed to justify acts of licentiousness injurious to morals or dangerous to the peace and safety of the state, or to exclude the Holy Bible from use in any public school of this state.

Section 19 originally banned düello:

Human life shall not be imperiled by the practice of dueling; and any citizen of this state who shall hereafter fight a duel, or assist in the same as second, or send, accept, or knowingly carry a challenge therefor, whether such an act be done in the state, or out of it, or who shall go out of the state to fight a duel, or to assist in the same as second, or to send, accept, or carry a challenge, shall be disqualified from holding any office under this Constitution, and shall be disenfranchised.

The repeal of Section 19 was proposed by Laws of 1977, and upon ratification by the electorate on November 7, 1978, was deleted from the Constitution by proclamation of the Secretary of State on December 22, 1978.

Article 4: Legislative Department

Sections 33–39 define the state Senate and House of Representatives while Sections 40–53 define qualifications and impeachment procedures.

An extensive portion of the article (Sections 54–77) is devoted to the rules of procedure in the legislature, particularly in regards to appropriations bills.

Sections 78–86 list a series of laws that the Mississippi Legislature is gereklidir to pass, while Sections 87–90 list requirements and prohibitions involving local and special laws. Sections 91–100 list additional laws which the Legislature may not pass (Section 98, which prohibited lotteries, was repealed in 1992).

Section 101 defines Jackson, Mississippi as the state capital and states that it may not be moved absent voter approval.

Sections 102–115 contain a series of miscellaneous provisions, including a unique section (106) dealing with the State Librarian. Section 105 was repealed in 1978.

Article 5. Executive

Sections 116–127 and 140–141 deal with the office of the Mississippi Valisi.

Section 140 had established a system of 'electoral votes' with each state House district having one electoral vote, with a candidate requiring a majority of both the popular and electoral vote to be elected Governor. This system was removed as a result of Statewide Measure 2 in 2020, being replaced with a popular vote: however, if no candidate receives a majority, a runoff election will be held between the top two candidates.

Section 141, which Statewide Measure 2 repealed, stated that if no candidate had received a majority of both the popular and the electoral vote, then a contingent election would be held in the Mississippi Temsilciler Meclisi between the top two candidates with the most votes to determine the Governor. This Section came into play only once during its existence, in 1999, ne zaman Ronnie Musgrove received 61 electoral votes, one short of a majority, and was also 2936 votes (0.38%) short of a popular vote majority: the House elected Musgrove on the first ballot.

Sections 128–132 deal with the office of the Mississippi Valisi Teğmen, while Section 133 deals with the Secretary of State, Section 134 with the State Treasurer and Auditor of Public Accounts. Sections 135, 136 and 138-139 deal with county and municipal officers (Section 137 was repealed in 1990).

Section 142 stated that, if the House of Representatives chose the Governor under the provisions of Section 141, then no member of the House was eligible for any state appointment, and Section 143 stated that all state officers shall be elected at the same time and in the same manner as the Governor: both Sections were repealed under Statewide Measure 2.

Article 6. Judiciary

Section 144 states that the judicial power of the State is vested in the Mississippi Yüksek Mahkemesi and in such other courts as provided for in the Constitution.

Sections 145–150 (and Section 151 until its repeal in 1914) discuss the number, qualifications, and terms of the Supreme Court's judges (as they are called). Each judge serves an elected eight-year term (Section 149). In an odd series of provisions, Section 145 states that the number of Supreme Court judges shall be three with two forming a quorum, amended by Section 145A which states that it shall be six ("that is to say, of three judges in addition to the three provided for by Section 145 of this Constitution") with four forming a quorum, then further amended by Section 145B which states that it shall be nine ("that is to say, of three judges in addition to the six provided for by Section 145-A of this Constitution") with five forming a quorum.

Sections 152–164 discuss the establishment, qualifications, and terms of the circuit and chancery court judges. All such judges serve elected four-year terms (Section 153).

Section 166 places a prohibition against reducing the salary of any judge during his/her term in office.

Section 167 states that all civil officers are conservators of the peace.

Section 168 discusses the role of the court clerks.

Section 169 discusses how all processes are to be styled, that prosecutions are to be carried on in the name and by the authority of the "State of Mississippi", and requires that any iddianame be concluded with the phrase "against the peace and dignity of the state."

Section 170 states that each county shall be divided into five districts, with a "resident freeholder" of each district to be elected, and the five to constitute the "Board of Supervisors" for the county. Section 176 further enforces the requirement that a Supervisor be a property owner in the district to which s/he is elected. (A 1990 proposed amendment to these sections was rejected.) It is not known whether the provisions are enforceable.

Section 171 allows for creation of justice courts and constables in each county, with a minimum of two justice court judges in each county. All judges and constables serve elected four-year terms.

Section 172 allows the Mississippi Yasama Meclisi to create and abolish other inferior courts.

Section 172A contains a prohibition against any court requiring the state or any political subdivision (or any official thereof) to levy or increase taxes.

Section 173 discusses the election of the Mississippi Başsavcı while Section 174 discusses the elections of the district attorneys for each circuit court. All such officials serve elected four-year terms.

Section 175 allows for the removal of public officials for willful neglect of duty or misdemeanor, while Section 177 allows for the Governor to fill judicial vacancies in office subject to Senate approval.

Section 177A creates a commission on judicial performance, which has the power to recommend removal of any judge below the Supreme Court (however, only the Supreme Court can order such removal), and also has the power to remove a Supreme Court judge upon 2/3 vote.

Article 7. Corporations

Sections 178–183 and 190–200 deal generally with corporations and related tax issues. Section 183 prohibits any county, town, city, or municipal corporation from owning stock or loaning money to corporations.

Sections 184–188, 193, and 195 deal with railroads (Sections 187, 196, and 197 also dealt with railroads and similar companies, but were later repealed).

Section 198A, added in 1960, declares Mississippi to be a right-to-work state (though several other states have similar provisions, this is one of only five such provisions included in a state Constitution).

Article 8. Education

Sections 201–212 discuss the State Board of Education, the State and county school board superintendents, and generally the establishment and maintenance of free public schools, including those for disabled students. Sections 205 and 207, as well as the later-added 213B, were later repealed: Section 207, which required schools to be racially segregated, was repealed on December 22, 1978, 24 years after the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled such laws in violation of the U.S. Constitution. [55]

Sections 213 and 213A discuss higher education.

Article 9. Militia

Sections 214–222 discuss the Mississippi Ulusal Muhafız.

Article 10. The Penitentiary and Prisons

Sections 224 and 225 allow the State to require convicts to perform labor, either in state industries or by working on public roads or levees (but not to private contractors); Section 225 also granted the state the power to separate "white" and "black" convicts, however this power was later repealed. Section 226 prohibits any convicts in county jails from being hired outside the county.

Section 223 was repealed in 1990.

Article 11. Levees

Sections 227–239 generally discuss the creation of levee districts within the State. The text discuss the two levee districts which were created prior to the adoption of the current Constitution – the district for the Mississippi Nehri and the district for the Yazoo Nehri.

Article 12. Franchise

Sections 240–253 discuss matters related to voting.

Section 214 required an elector to be a resident of the state and county for at least one year prior to an election, and six months resident within the municipality they desired to register to be an elector. These were later determined to be unconstitutional by a US Federal Circuit Court in Graham v. Waller, as they served no compelling state interest, and a 30-day residency requirement was instituted in the same judicial order on a temporary basis.[56] Subsequent statutes passed by the legislature kept the 30 day residency requirement.

Sections 241A, 243, and 244 were later repealed: all three were designed, in some part, to disenfranchise minority voters (241A required that a person be "of good moral character", 243 instituted a anket vergisi, and 244 instituted a okuryazarlık testi, all of which have been ruled unconsitutional).

Article 13. Apportionment

This article consists of only Section 254, which states how the State shall be apportioned into State Senatorial ve Eyalet Temsilcisi districts after every Federal census, provided the State Senate shall consist of no more than 52 Senators, and the State House shall consist of no more than 122 Representatives.

Sections 255 and 256 were later repealed.

Article 14. General Provisions

Sections 257 through 272A contain miscellaneous other provisions not related to other Articles.

Section 263, which made illegal the marriage of a "white person" to a "negro" or "mulatto", was ruled to be unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1967, and was formally repealed in December 1987.

Section 263A, enacted in 2004, defines marriage as between a male and a female; however, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2015 that such laws violated the U.S. Constitution.

Section 265 prohibits any person who "denies the existence of a Supreme Being" from holding state office. This requirement, as well as similar provisions in several other state constitutions, violates the İlk Değişiklik 's prohibition on the establishment of religion and as the prohibition on any kind of religious test located in Article 6 of the federal constitution.[57]

Sections 269, 270 and 272 were repealed.

Article 15. Amendments to the Constitution

Amendments may be made by either the Mississippi Yasama Meclisi veya tarafından girişim, according to Section 273.

For Legislature-proposed amendments, 2/3 of each house must approve the amendment, plus a majority of the voters.

The number of signatures required for an initiative-proposed amendment must be at least 12% of the total votes cast for Mississippi Valisi in the most recent gubernatorial election, provided that no more than 20% of the signatures can come from any one congressional district. As Mississippi currently has only four districts, a strict interpretation of this section makes it impossible to propose an amendment via initiative.

The Article excludes certain portions of the Constitution that can be amended by initiative; for example, any of the sections in Article 3 (Bill of Rights) are off-limits.

The Article also discusses the procedures in the event that a Legislature-proposed amendment is similar to that of an initiative-proposed amendment.

Sections 274 through 285 contain transitional provisions.

Previously the Article contained Sections 286 and 287 which were classified as "ADDITIONAL SECTIONS OF THE CONSTITUTION OF MISSISSIPPI NOT BEING AMENDMENTS OF PREVIOUS SECTIONS"; these were later renumbered as 145A and 149A and placed under the article related to the judiciary.

Ayrıca bakınız

- Benjamin Tillman

- Siyah Kodlar

- Konfederasyon Devletlerinin Anayasası

- Güney Carolina Eyaleti Anayasası

- Yaldızlı Çağ

- Demokrat Parti Tarihi

- History of the State of Mississippi

- James K. Vardaman

- Jim Crow yasaları

- Beyaz Kamelya Şövalyeleri

- Amerika Birleşik Devletleri'nde linç

- Amerikan İç Savaşı'nda Mississippi

- Amerikan ırk ilişkilerinin Nadir'i

- Yeniden Yapılanma Dönemi

- Kırmızı Gömlekler

- Kurtarıcılar

- Beyaz Lig

Notlar

- ^ Some segments of the constitution took effect on January 1, 1892 and January 1, 1896.

Referanslar

- ^ a b c d e f g h ben Hannah, et al. 1965, s. 3.

- ^ Mississippi Arşivler ve Tarih Bölümü. "Old Capitol Museum". Mississippi Arşivler ve Tarih Bölümü. Mississippi: State of Mississippi. Arşivlenen orijinal 20 Ağustos 2015. Alındı 3 Ağustos 2015.

The Old Capitol was the site of some of the state's most significant legislative actions, such as the passage of the 1839 Married Women's Property Act, Mississippi's secession from the Union in 1861, and the crafting of the 1868 and 1890 state constitutions.

- ^ a b c d e f g h ben j k l m Waldrep 2010, s. 223.

- ^ a b c d e f g h ben Kestenbaum, Lawrence (October 2, 2012). "Episcopalian Politicians in Mississippi (including Anglican)". Siyasi Mezarlık. Ann Arbor, Michigan: The Political Graveyard. Arşivlenen orijinal 6 Kasım 2012 tarihinde. Alındı 6 Kasım 2012.

Solomon Saladin Calhoon (1838-1908)

- ^ a b Glass, Andrew. "Mississippi readmitted to the Union Feb. 23, 1870". Politico. Capitol News Company LLC. Alındı 4 Ağustos 2015.

- ^ a b c d McMillen 1990, s. 41–44.

- ^ a b c Diner 1998, s. 127.

- ^ a b c d e f g Skates, John Ray (September 2000). "The Mississippi Constitution of 1868". Mississippi: Mississippi Historical Society. Arşivlenen orijinal 20 Kasım 2009. Alındı 20 Kasım 2009.

- ^ a b Mississippi Department of Archives and History (January 24, 2014). "Black Codes to Brown v. Board at Old Capitol". Mississippi Arşivler ve Tarih Bölümü. Mississippi: State of Mississippi. Arşivlenen orijinal 30 Nisan 2014. Alındı 30 Nisan, 2014.

Yazarlar Jere Nash ve Michael Williams, yeni serbest bırakılan kölelerin yasama meclisinde görev yaptığı yeni kölelerin haklarını sınırlamak için yasa koyucuların 1865 Kara Yasa'yı yürürlüğe koyduğu Meclis Meclisi'nde 1865'ten 1955'e kadar sivil ve oy hakları mücadelesini tartışacaklar. Yeniden Yapılanma sırasında ve 1890 Anayasasının siyah Mississippians'tan mahrum etmek için kabul edildiği yer.

- ^ a b Freeland, Tom (3 Kasım 2011). ""niyetiyle ... franchise üzerine bir tıkanma olarak: "1896'da Mississippi Yüksek Mahkemesi, devletin siyahları nasıl haklarından mahrum ettiğini açıklıyor". NMissCommentor: Kuzey Mississippi'deki tepelerden bir blog. Mississippi: T. Freeland. Arşivlenen orijinal 13 Mart 2012. Alındı 3 Ağustos 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Richmond Üniversitesi (2008). "1895 Güney Karolina Anayasa Sözleşmesi". Tarih Motoru: İşbirliğine Dayalı Eğitim ve Araştırma Araçları. Virginia: Richmond Üniversitesi. Arşivlenen orijinal 11 Haziran 2010. Alındı 11 Haziran 2010.

- ^ a b c d Kamu Yayın Hizmeti (Eylül 2008). "İnsanlar ve Etkinlikler: James K. Vardaman". Amerikan Deneyimi. Kamu Yayınları Kurumu. Arşivlenen orijinal 20 Mart 2012. Alındı 21 Eylül 2008.

Gerekirse eyaletteki her zenci linç edilecek; beyaz üstünlüğünü korumak için yapılacaktır.

- ^ a b c d e Tahmassebi 1991, s. 67.

- ^ a b c d e Cramer, Clayton E. (1995). "Silah Kontrolünün Irkçı Kökleri". Kansas Hukuk ve Kamu Politikası Dergisi. Arşivlenen orijinal 5 Haziran 2004. Alındı 5 Haziran 2004.

- ^ a b c d e Winkler, Adam (9 Ekim 2011). "Silah Kontrolü Irkçı mı ?: Yazar Adam Winkler, Amerika'daki silah kontrolünün şaşırtıcı ırkçı köklerini ortaya çıkarıyor". Günlük Canavar. Daily Beast Company, LLC. Arşivlenen orijinal 10 Ekim 2011 tarihinde. Alındı 10 Ekim 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Loewen, James W. (19 Temmuz 2015). "Maryland'in Konfederasyon Anıtı Rockville Bize İç Savaş Hakkında Ne Anlatıyor? Nadir Hakkında? Bugün Hakkında?". Tarih Haber Ağı. Arşivlenen orijinal Ağustos 2, 2015. Alındı 2 Ağustos 2015.

Konfederasyonlar - neo-Konfederasyonlar demeliyiz, çünkü 1890'da çoğunlukla yeni bir kuşaktılar - 1890'da İç Savaşı kazandılar. Bunu çeşitli şekillerde kazandılar. Birincisi, o yıl ne anlama geldiğini kazandılar: beyaz üstünlüğü. Mississippi eyaleti yeni anayasasını kabul etti. Afrikalı Amerikalıların oy kullanmasına izin vermesi dışında 1868 anayasasında yanlış bir şey yoktu. 1890'da anayasal konvansiyonlarında beyaz Mississippi'liler netti. Bir delegenin dediği gibi, 'Evrenin dibini patlatırsa gerçeği söyleyelim. Zencileri dışlamak için buraya geldik. Bundan başka hiçbir şey cevap vermeyecek. ' Bunu yapmak için en önemli hüküm, seçmenlerin eyalet anayasasının herhangi bir bölümünü 'makul bir şekilde yorumlayabilmesini' gerektiren 244. Bölüm'dü. Beyaz kayıt memurları "makul" olduğuna karar verir. Güneydeki diğer eyaletler, 1907'de Oklahoma da dahil olmak üzere 'Mississippi Planı' olarak adlandırılan planı kopyaladılar.

- ^ a b c d e f g h ben j Minor, Bill (2 Temmuz 2015). "Küçük: Hem 1890 Anayasası hem de bayrak gitmeli". Clarion-Defter. Gannett. Alındı 4 Ağustos 2015.

1870 yasası uyarınca Kongre, eyaletin anayasasını değiştirmemesi veya değiştirmemesi koşuluyla Mississippi'yi yeniden kabul etti. (Bu, halkın oylamasına sunulan tek anayasa olan ve o zamanlar Cumhuriyetçiler olarak bilinen siyah vatandaşlardan önemli katkılar alan 1868 anayasası anlamına geliyordu.) 1947 tarihli değerli kitabı "The Negro in Mississippi - 1865-1890" Eski Millsaps College tarih profesörü Vernon Lane Wharton, 1868 anayasasının, o zamanlar popüler olan General Alvin Gillem yönetimindeki federal işgalin daha sonra kazanılması beklenen ulusal Demokrat parti zaferiyle sona ereceği bilgisinin gücü üzerine o günün seçmenleri tarafından kabul edildiğini anlatıyor. yıl. Wharton'ın Mississippi'deki Yeniden Yapılanma dönemine ilişkin keskin çalışması, büyük ölçüde, düzinelerce ilçe ve küçük kasabada yoğun partizan gazetelerin külçeleri için halkın ve siyasi liderlerinin ne düşündüğünü araştırmaya dayanıyor. Wharton çalışmasında, o zamanın Demokratları 1890'da yeni bir anayasa çıkardıklarında, herhangi bir yeni eyalet anayasasının siyahların oy kullanma ve kamu görevinde bulunma haklarını koruması gerektiği şeklindeki 1870 kongre yetkisine uyma niyetinde olmadıklarını açıkça ortaya koyuyor.

- ^ Lincoln, Abraham (26 Haziran 1857). "Springfield, Illinois'de Konuşma". Springfield, Illinois. Arşivlenen orijinal 8 Eylül 2002. Alındı 8 Eylül 2002.

- ^ Kolchin 1993, s. 73.

- ^ Lincoln, Abraham (24 Ağustos 1855). Roy P. Basler; et al. (eds.). "Joshua Speed'e Mektup". Abraham Lincoln'ün Toplanan Eserleri. Abraham Lincoln Çevrimiçi. Alındı 7 Ağustos 2015.

- ^ a b Foner 2009, s. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f Educational Broadcasting Corporation (28 Aralık 2002). "Williams - Mississippi (1898)". Jim Crow Hikayeleri: Jim Crow'un Yükselişi ve Düşüşü. Kamu Yayın Hizmeti. Arşivlenen orijinal 5 Nisan 2003. Alındı 5 Nisan, 2003.

- ^ a b c d e f Ron (10 Eylül 2012). "Seçmen Haklarından Mahrum Kalma, Mississippi tarzı". ABD Köle. Blogspot. Arşivlenen orijinal Ağustos 2, 2015. Alındı 2 Ağustos 2015.

- ^ "HR 1096: Mississippi Eyaletini Amerika Birleşik Devletleri Kongresinde temsil edilmek üzere kabul etmek. Mississippi halkı cumhuriyetçi bir Eyalet hükümeti anayasası hazırlayıp kabul ederken; Mississippi yasama organı ise Amerika Birleşik Devletleri'nde temsil edilme hakkına sahiptir. Birleşik Devletler Kongresi ". 23 Şubat 1870.'den arşivlendi orijinal Ağustos 5, 2015. Alındı 5 Ağustos 2015.

- ^ a b Çiçek 1884, s. 449.

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (7 Aralık 1869). "Birleşik Milliyetimiz". Amerikan Tarihini Öğretmek. Boston, Massachusetts: Ashbrook Center, Ashland Üniversitesi, Ashland, Ohio. Alındı 5 Ağustos 2015.

- ^ Grant 1878, s. 251–252.

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (Mayıs 1886). "Renkli Irkların Geleceği".

- ^ Boutwell, George Sewall (1876). "Mississippi, 1875: 1875 Mississippi Seçimini Soruşturmak İçin Seçilmiş Komite Raporu". Amerika Birleşik Devletleri Senatosu. Amerika Birleşik Devletleri Kongresi. Alındı 3 Ağustos 2015.

- ^ Taş, John M. (11 Mart 1890). "İlan". Jackson Mississippi: Mississippi Eyaleti İcra Dairesi. Arşivlenen orijinal Ekim 2, 2015. Alındı 5 Ağustos 2015.

- ^ Coski 2005, s. 80–81.

- ^ a b McMillen 1990, s. 41.

- ^ a b Martin 1890, s. 94.

- ^ Behrans, vd. 2003, s. 569.

- ^ Behrans, vd. 2003, s. 598.

- ^ Harper's Weekly (5 Eylül 1868). "Bu Bir Beyaz Adamın Hükümeti". Harper's Weekly. Harper's Weekly. s. 568. Arşivlenen orijinal 4 Ağustos 2015. Alındı 4 Ağustos 2015.

- ^ Demokratik Ulusal Kongre (4 Temmuz 1868). "1868 Demokratik Parti Platformu". Demokratik Ulusal Sözleşme. Arşivlenen orijinal Ağustos 3, 2015. Alındı 3 Ağustos 2015.

Demokrat parti [...] Özgür Adamlar Bürosu'nun kaldırılmasını [...] talep ediyor; ve zenci üstünlüğünü güvence altına almak için tasarlanmış tüm siyasi araçlar [...]