Hindenburg felaket - Hindenburg disaster

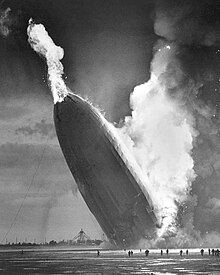

Kıç Hindenburg ön planda demirleme direği ile düşmeye başlar. | |

| Kaza | |

|---|---|

| Tarih | 6 Mayıs 1937 |

| Özet | İniş sırasında alev aldı; belirsiz neden |

| Site | NAS Lakehurst, Manchester İlçesi, New Jersey, ABD Koordinatlar: 40 ° 01′49″ K 74 ° 19′33″ B / 40.0304 ° K 74.3257 ° B |

| Toplam ölümler | 36 |

| Uçak | |

| Uçak tipi | Hindenburg-sınıf zeplin |

| Uçak adı | Hindenburg |

| Şebeke | Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei |

| Kayıt | D-LZ129 |

| Uçuş menşei | Frankfurt am Main, Hesse-Nassau, Prusya, Almanya |

| Hedef | NAS Lakehurst, Lakehurst İlçesi, New Jersey, ABD |

| Yolcular | 36 |

| Mürettebat | 61 |

| Ölümler | 35 (13 yolcu, 22 mürettebat) |

| Hayatta kalanlar | 62 (23 yolcu, 39 mürettebat) |

| Kara zayiatı | |

| Kara ölümleri | 1 |

Hindenburg felaket 6 Mayıs 1937'de meydana geldi. Manchester Township, New Jersey, Amerika Birleşik Devletleri. Alman yolcu zeplin LZ 129 Hindenburg yanmış ve yanaşma girişimi sırasında tahrip olmuştur. bağlama direği -de Donanma Hava İstasyonu Lakehurst. Gemideki 97 kişiden (36 yolcu ve 61 mürettebat) 35 ölüm (13 yolcu ve 22 mürettebat) ve yerde ek bir ölüm meydana geldi.

Afet konusu oldu haber filmi kapsamı, fotoğraflar ve Herbert Morrison iniş alanından ertesi gün yayınlanan radyo görgü tanıklarının kaydedilmiş raporları.[1] Hem tutuşmanın nedeni hem de çıkan yangının ilk yakıtı için çeşitli hipotezler öne sürülmüştür. Olay, halkın dev, yolcu taşıyan sert hava gemisine olan güvenini sarsmış ve uçağın ani sonunu işaretlemiştir. zeplin çağı.[2]

Uçuş

1937 sezonunu tek bir gidiş-dönüş geçişi tamamlayarak açtıktan sonra Rio de Janeiro Brezilya, Mart ayı sonlarında Hindenburg ayrıldığı yer Frankfurt Almanya, 3 Mayıs akşamı, Avrupa ile Amerika Birleşik Devletleri arasında ticari hizmetinin ikinci yılı için planlanan 10 gidiş-dönüş yolculuğunun ilkinde. Amerikan Havayolları operatörleri ile sözleşme yapmıştı Hindenburg Lakehurst'tan Newark'a yolcuları uçak uçuşlarına bağlantı için taşımak.[3]

Güçlü olanlar hariç karşıdan esen rüzgarlar ilerlemesini yavaşlatan Atlantik geçişi Hindenburg aksi takdirde, hava gemisi üç gün sonra 6 Mayıs'ta Lakehurst'e akşam erken iniş girişiminde bulunana kadar önemsizdi. Hindenburg dönüş uçuşu için tamamen doluydu. Almanya'ya bileti olan yolcuların çoğu, Kral George VI ve Kraliçe Elizabeth'in taç giyme töreni sonraki hafta Londra'da.

Zeplin 6 Mayıs sabahı Boston üzerinden geçtiğinde programın birkaç saat gerisindeydi ve Lakehurst'a inişinin öğleden sonra nedeniyle daha da gecikmesi bekleniyordu. gök gürültülü fırtınalar. Lakehurst'teki kötü hava koşulları hakkında bilgi verdi, Kaptan Max Pruss bir rota çizdi Manhattan Adası, insanlar zeplin görüntüsünü yakalamak için sokağa koşarken halka açık bir gösteriye neden oldu. Saat 16: 00'da sahayı geçtikten sonra, Kaptan Pruss, yolcuları deniz kenarlarında bir tura çıkardı. New Jersey havanın düzelmesini beklerken. Nihayet 18: 22'de bilgilendirildikten sonra. Fırtınaların geçtiğini belirten Pruss, inişini neredeyse yarım gün geç yapmak için zeplin Lakehurst'e geri yönlendirdi. Bu, zeplin hizmete alınması ve Avrupa'ya planlanan kalkışı için hazırlanması için beklenenden çok daha az zaman bırakacağından, halka bağlama yerinde izin verilmeyeceği veya gemiyi ziyaret edemeyeceği bildirildi. Hindenburg limanda kaldığı süre boyunca.

İniş zaman çizelgesi

Akşam 7:00 civarı. yerel saat, 650 fit (200 m) yükseklikte, Hindenburg Lakehurst Donanma Hava İstasyonuna son yaklaşımını yaptı. Bu, yüksek iniş olacaktı. uçan palamar, çünkü zeplin iniş halatlarını ve demirleme halatlarını yüksek bir rakımda düşürür ve ardından bağlama direği. Bu tür bir iniş manevrası, yerdeki ekiplerin sayısını azaltacak, ancak daha fazla zaman gerektirecektir. Yüksek iniş Amerikan hava gemileri için yaygın bir prosedür olsa da, Hindenburg Lakehurst'a inerken bu manevrayı sadece 1936'da birkaç kez yapmıştı.

Saat 19: 09'da, zeplin, yer ekibi hazır olmadığı için, iniş alanı çevresinde batıya tam hızla keskin bir dönüş yaptı. Saat 19: 11'de iniş alanına döndü ve valfli gaza döndü. Tüm motorlar önde rölantide geçti ve zeplin yavaşlamaya başladı. Kaptan Pruss, kıç motorları 19: 14'te tam arkaya sipariş etti. 394 ft (120 m) yükseklikte iken, zeplin frenlemeye çalışın.

Saat 19: 17'de rüzgar doğudan güneybatıya doğru kaydı ve Kaptan Pruss ikinci bir keskin dönüş emri verdi. sancak bağlama direğine doğru s şeklinde bir uçuş yolu yapmak. Saat 19: 18'de, son dönüş ilerledikçe, Pruss 300, 300 ve 500 kg (660, 660 ve 1100 lb) su balastını art arda düşürdü çünkü zeplin kıç ağırlığındaydı. İleri gaz hücreleri de valfli idi. Bu tedbirler gemiyi düzeltemediğinden, altı adam (kazada üçü hayatını kaybetti)[Not 1] daha sonra gönderildi eğilmek zeplin kırpmak için.

19: 21'de, Hindenburg 295 ft (90 m) yükseklikte demirleme halatları pruvadan düşürüldü; önce sancak hattı düşürüldü, ardından Liman hat. İskele hattı, yer vincinin direğine bağlandığı için aşırı sıkıldı. Sancak hattı hala bağlanmamıştı. Yer ekibi bağlama halatlarını tutarken hafif bir yağmur yağmaya başladı.

Saat 19: 25'te birkaç tanık, üst yüzgecin önündeki kumaşın gaz sızıyormuş gibi dalgalandığını gördü.[4] Diğerleri soluk mavi bir alev gördüklerini bildirdi - muhtemelen Statik elektrik veya St Elmo'nun Ateşi - Alevlerin ilk göründüğü noktaya yakın geminin tepesinde ve arkasında yangından birkaç dakika önce.[5] Diğer bazı görgü tanıklarının ifadeleri, ilk alevin iskele tarafında iskele yüzgecinin hemen önünde göründüğünü ve onu tepede yanan alevlerin izlediğini öne sürüyor. Komutan Rosendahl üst yüzgecin önündeki alevlerin "mantar şeklinde" olduğuna tanıklık etti. Sancak tarafındaki bir tanık, o tarafta dümenin altından ve arkasından çıkan bir yangını bildirdi. Gemide insanlar boğuk bir patlama duydular ve geminin önündekiler iskele ipi aşırı gerilirken bir şok hissettiler; Kontrol arabasındaki memurlar başlangıçta şokun kopmuş halattan kaynaklandığını düşündü.

Felaket

19: 25'te. yerel saat Hindenburg alev aldı ve hızla alevler içinde kaldı. Görgü tanıklarının ifadeleri, yangının başlangıçta nerede çıktığı konusunda hemfikir değil; İskele tarafındaki birkaç tanık, sarı-kırmızı alevlerin ilk önce 4. ve 5. hücrelerin havalandırma bacasının yakınındaki üst kanattan ileri atladığını gördü.[4] İskele tarafındaki diğer tanıklar, yangının aslında yatay iskele yüzgecinin hemen önünde başladığını, ancak ardından üst yüzgecin önünde alevlerin geldiğini kaydetti. Sancak tarafına bakan biri, dümenlerin arkasındaki 1. hücreye yakın, alçaktan ve kıçtan alevlerin başladığını gördü. Zeplin içinde, dümenci Helmut Lau Alt yüzgecde bulunan, boğuk bir patlama işittiğini ifade etti ve 4 numaralı gaz hücresinin ön bölmesinde "ısı nedeniyle aniden kaybolan" parlak bir yansıma görmek için yukarı baktı. Diğer gaz hücreleri alev almaya başlayınca yangın sancak tarafına daha fazla yayıldı ve gemi hızla düştü. Dört haber ekibinden kameramanlar ve inişi çektiği bilinen en az bir seyirci ve olay yerinde çok sayıda fotoğrafçı olmasına rağmen, yangının başladığı an için bilinen bir görüntü veya fotoğraf mevcut değil.

Alevlerin başladığı her yerde, hızla ilk tüketen hücreler 1'den 9'a kadar yayıldılar ve yapının arka ucu patladı. Neredeyse anında, patlamanın şoku sonucunda iki tank (su veya yakıt içerip içermediği tartışılır) gövdeden fırladı. Yüzdürme geminin kıç tarafında kayboldu ve geminin sırtı kırılırken pruva yukarı doğru sallandı; düşen kıç trimde kaldı.

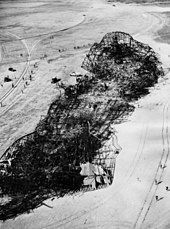

Kuyruğu gibi Hindenburg yere düştü, burnundan alevler yükseldi ve pruvadaki 12 mürettebat üyesinden 9'u öldü. Geminin pruva kısmında hala gaz vardı, bu yüzden kıç çökerken yukarı doğru işaret etmeye devam etti. Yolcu güvertesinin arkasındaki hücre, yan taraf içe doğru çökerken tutuştu ve "Hindenburg" yazan kırmızı harflerle, pruva alçalırken alevler tarafından silindi. Zeplin gondol çarkı yere değdi ve son bir gaz hücresi yanarken pruvanın hafifçe zıplamasına neden oldu. Bu noktada, gövdedeki kumaşın çoğu da yanmış ve pruva sonunda yere düşmüştür. rağmen hidrojen yanmayı bitirdi, Hindenburg's dizel yakıt birkaç saat daha yandı.

İlk afet belirtilerinden pruvanın yere çarpmasına kadar geçen süre genellikle 32, 34 veya 37 saniye olarak rapor edilir. Yangın ilk başladığında haber filmlerinden hiçbiri hava gemisini filme almadığından, başlama zamanı yalnızca çeşitli görgü tanıklarının hesaplarından ve kazanın en uzun görüntülerinin süresinden tahmin edilebilir. Dikkatli bir analiz NASA 's Addison Bain alevin ön yayılma hızını çarpma sırasında bazı noktalarda yaklaşık 49 ft / s (15 m / s) olarak verir, bu da yaklaşık 16 saniyelik bir toplam imha süresiyle sonuçlanırdı (245 m / 15 m / s = 16.3 s).

Bazıları duralumin Zeplin çerçevesi kurtarıldı ve geri dönüştürüldüğü ve askeri uçak yapımında kullanıldığı Almanya'ya geri gönderildi. Luftwaffe çerçeveler gibi LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin ve LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II her ikisi de 1940'ta hurdaya çıkarıldığında.[6]

Felaketten sonraki günlerde, yangının nedenini araştırmak için Lakehurst'te resmi bir araştırma kurulu kuruldu. ABD Ticaret Bakanlığı'nın soruşturmasına Albay South Trimble Jr başkanlık ederken, Dr. Hugo Eckener Alman komisyonunu yönetti.

Haber programı

Felaket iyi belgelendi. Zeplin tarafından yılın ilk transatlantik yolcu uçuşu hakkında yoğun tanıtım Amerika Birleşik Devletleri çıkartmaya çok sayıda gazeteciyi çekmişti. Bu nedenle, hava gemisinin patladığı sırada birçok haber ekibi sahadaydı ve bu nedenle önemli miktarda haber vardı. haber filmi kapsama ve fotoğrafların yanı sıra Herbert Morrison radyo istasyonu görgü tanığı raporu WLS içinde Chicago Ertesi gün yayınlanan bir haber.

Morrison'un yayınının bazı bölümleri daha sonra seslendirildi haber filmi kamera görüntüsü. Bu, kelimelerin ve filmin birlikte kaydedildiği izlenimini verdi, ancak durum böyle değildi.

Neredeyse hareketsiz duruyor şimdi geminin burnundan ipler attılar; ve (uh) sahada bir dizi adam tarafından ele geçirildiler. Yine yağmur yağmaya başlıyor; o ... yağmur biraz yavaşlamıştı. Geminin arka motorları onu (uh) onu uzak tutacak kadar tutuyor ... Alevler içinde! Bunu al Charlie; Bunu al Charlie! Bu ateş ... ve çöküyor! Korkunç çöküyor! Aman! Yoldan çekil lütfen! Yanıyor ve alevler içinde patlıyor ... ve demirleme direğine ve aradaki tüm insanlara düşüyor. Bu korkunç; bu dünyadaki en kötü felaketlerden biridir. Oh bu ... [anlaşılmaz] alevleri ... Çarpıyor, oh! oh, gökyüzüne dört ya da beş yüz fit derinlik ve korkunç bir çökme, bayanlar ve baylar. Duman var ve şimdi alevler var ve iskelet, demirleme direğine değil, yere çarpıyor. Oh, insanlık ve buralarda çığlık atan tüm yolcular! Sana söylemiştim; o - İnsanlarla konuşamıyorum bile, arkadaşları orada! Ah! Bu ... bu ... bu bir ... ah! Ben ... konuşamam bayanlar ve baylar. Dürüst: Sadece orada yatıyor, bir yığın duman enkazı. Ah! Ve herkes güçlükle nefes alıp konuşabiliyor ve çığlık atıyor. Ben ... ben ... üzgünüm. Dürüst: Ben ... Zor nefes alıyorum. Ben ... Göremediğim bir yere içeri gireceğim. Charlie, bu korkunç. Ah, ah ... Yapamam. Dinleyin millet; Ben ... Bir dakikalığına durmam gerekecek çünkü sesimi kaybettim. Bu tanık olduğum en kötü şey.

Haber filmi görüntüleri, dört haber filmi kamera ekibi tarafından çekildi: Pathé Haberleri, Movietone Haberleri, Hearst Günün Haberleri, ve Paramount Haberleri. Al Gold of Fox Movietone News daha sonra çalışmaları için bir Başkanlık Alıntı aldı.[9][10] Afetin en çok dolaşan fotoğraflarından biri (makalenin üstündeki fotoğrafa bakın), zeplin demirleme direğiyle çarpışmasını gösteren, International News Photos'tan Sam Shere tarafından fotoğraflandı. Yangın başladığında, kamerayı gözünün önüne koyacak ve fotoğrafı "kalçasından" çekecek vakti yoktu. Murray Becker İlişkili basın 4 x 5 ile zeplin hala omurgadayken yutan yangını fotoğrafladı Hız Grafiği kamera. Bir sonraki fotoğrafı (sağa bakın), pruva yukarı doğru iç içe geçerken burundan çıkan alevleri gösteriyor. Profesyonel fotoğrafçıların yanı sıra izleyiciler de kazayı fotoğrafladı. 1 Nolu Hangar yakınlarındaki seyirci alanına yerleştirildiler ve hava gemisinin yandan arkadan görünümleri vardı. Gümrük komisyoncusu Arthur Cofod Jr. ve 16 yaşındaki Foo Chu'nun ikisi de Leica kameralar yüksek hızlı film ile, basın fotoğrafçılarından daha fazla sayıda fotoğraf çekmelerini sağlar. Cofod'un dokuz fotoğrafı Hayat dergi[11] Chu'nun fotoğrafları New York Daily News.[12]

Morrison'un tutkulu haberciliği ile birlikte haber filmleri ve fotoğraflar, halkın ve endüstrinin hava gemilerine olan inancını paramparça etti ve dev yolcu taşıyan hava gemilerinin sonunu işaret etti. Ayrıca Zeppelins'in düşüşüne katkıda bulunan, uluslararası yolcu hava yolculuğunun gelişi ve Pan American Havayolları. Havadan daha ağır olan uçaklar, Atlantik ve Pasifik'i düzenli olarak 130 km / sa (80 mil / sa) hızından çok daha hızlı geçti. Hindenburg. Tek avantajı Hindenburg yolcularına sağladığı rahatlık bu tür bir uçağa sahipti.

Amerika Birleşik Devletleri'ndeki medyadaki haberin aksine, Almanya'daki felaketle ilgili medyada yer alan haberler daha bastırıldı. Afetin bazı fotoğrafları gazetelerde yayınlansa da haber filmi görüntüleri 2. Dünya Savaşı sonrasına kadar yayınlanmadı. Ek olarak, Alman kurbanlar, düşmüş savaş kahramanlarına benzer bir şekilde anıldılar ve zeplin inşasını finanse etmek için taban hareketleri (1908'de meydana gelen LZ 4 ) tarafından açıkça yasaklanmıştır Nazi hükümeti.[13]

Orada bir bir dizi diğer zeplin kazası öncesinde Hindenburg ateş; çoğu kötü hava koşullarından kaynaklanıyordu. Graf Zeppelin ilki dahil olmak üzere 1,6 milyon kilometreden (1,0 milyon mil) fazla güvenle uçmuştu. etrafını dolaşma bir zeplin tarafından dünyanın. Zeppelin şirketinin promosyonları, hava gemilerinde hiçbir yolcunun yaralanmadığı gerçeğini belirgin bir şekilde öne çıkardı.

Ölümler

Otuz altı yolcudan on üçü öldü ve altmış bir mürettebattan yirmi ikisi öldü; hayatta kalanların çoğu ciddi şekilde yakıldı. Ayrıca bir yer ekibi, sivil hat görevlisi Allen Hagaman öldürüldü.[14] On yolcu[Not 2] ve 16 mürettebat[Not 3] kazada veya yangında öldü. Kurbanların çoğu yanarak ölürken, diğerleri zeplin aşırı yükseklikte atlayarak ya da duman soluması ya da düşen enkaz sonucu öldü.[Not 4] Diğer altı mürettebat üyesi,[Not 5] üç yolcu[Not 6] ve Allen Hagaman sonraki saatlerde veya günlerde, çoğunlukla yanıklar nedeniyle öldü.[15]

Ölen mürettebatın çoğu, geminin gövdesinin içindeydiler, burada ya net bir kaçış rotası yoktu ya da çoğu ölümden kaçmak için havada çok uzun süre yanan halde asılı olan geminin pruvasına yakınlardı. . Pruvadaki mürettebatın çoğu yangında öldü, ancak en az biri pruvadan düşerken öldü. Ölen yolcuların çoğu, yolcu güvertesinin sancak tarafında mahsur kaldı. Sadece rüzgâr ateşi sancak tarafına doğru üflemekle kalmıyordu, aynı zamanda gemi yere otururken sancak tarafına da hafifçe yuvarlandı, geminin o kısmındaki üst gövdenin çoğu sancak tarafındaki gözetleme pencerelerinin dışına çökerek kesildi o taraftaki birçok yolcunun kaçışı.[Not 7] Daha da kötüsü, sancak yolcu alanından merkezi fuayeye açılan kayar kapı ve geçit merdivenleri (kurtarıcıların birkaç yolcuyu emniyete götürdüğü) çarpışma sırasında sıkıştı ve bu yolcuları sancak tarafında daha da kıstırdı.[Not 8] Yine de bazıları sancak tarafındaki yolcu güvertesinden kaçmayı başardı. Buna karşılık, geminin liman tarafındaki yolcuların birkaçı dışında hepsi yangından kurtuldu ve bazıları neredeyse yara almadan kurtuldu. En iyi hatırlanan hava gemisi felaketi olmasına rağmen, en kötüsü değildi. Helyum dolu ABD Donanması keşif zeplininin iki katından biraz fazlası (gemide 76'nın 73'ü) can verdi. USSAkron 4 yıl önce 4 Nisan 1933'te New Jersey kıyılarında denizde düştü.[16]

14 yaşındaki kamara çocuğu Werner Franz, başlangıçta geminin yandığını fark ettiğinde sersemlemişti, ancak üzerindeki bir su tankı patlayarak etrafındaki ateşi söndürdüğünde harekete geçmeye teşvik edildi. Yakındaki bir ambar kapısına doğru ilerledi ve tam da geminin ön kısmı kısa bir süre havaya sıçradığı sırada düştü. Sancak tarafına doğru koşmaya başladı ama durdu ve döndü ve diğer tarafa koştu çünkü rüzgar alevleri o yöne doğru itiyordu. Yaralanmadan kaçtı ve 2014'te öldüğünde hayatta kalan son mürettebat üyesiydi.[17] Hayatta kalan son kişi Werner G. Doehner, 8 Kasım 2019'da öldü.[18] Felaket anında Doehner sekiz yaşındaydı ve ailesiyle tatil yapıyordu.[18] Daha sonra annesinin kendisini ve kardeşini gemiden attığını ve peşlerinden atladığını hatırladı; hayatta kaldılar ama Doehner'ın babası ve kız kardeşi öldürüldü.[19]

Kontrol arabası yere düştüğünde, memurların çoğu pencerelerden atladı, ancak ayrıldı. Birinci Subay Yüzbaşı Albert Sammt, Kaptan Max Pruss'u hayatta kalanları aramak için enkaza tekrar girmeye çalışırken buldu. Pruss'un yüzü kötü bir şekilde yanmıştı ve aylarca hastanede kalması ve rekonstrüktif cerrahi geçirmesi gerekiyordu ama hayatta kaldı.[20]

Kaptan Ernst Lehmann kazadan başını ve kollarını yakarak ve sırtının çoğunda şiddetli yanıklarla kurtuldu. Ertesi gün yakındaki bir hastanede öldü.[21]

Yolcu Joseph Späh, vodvil komik akrobat, inişi filme aldığı kamera ile camı kırdığı ilk sorun işaretini gördü (film felaketten kurtuldu). Gemi yere yaklaştığında, kendini pencereden dışarı indirdi ve pencere pervazına asıldı ve gemi yerden yaklaşık 20 fit yüksekteyken gitmesine izin verdi. Akrobatının içgüdüleri devreye girdi ve Späh ayaklarını altında tuttu ve yere indiğinde bir güvenlik rulosu yapmaya çalıştı. Yine de ayak bileğini yaraladı ve yer ekibinin bir üyesi geldi, küçük Späh'ı bir kolunun altına astı ve onu ateşten kurtardığında sersemlemiş bir şekilde sürünüyordu.[Not 9]

Zeplin pruvasındaki 12 mürettebattan sadece üçü hayatta kaldı. Bu 12 adamdan dördü, pruvanın en ucunda, en öndeki iniş halatlarının ve çelik demirleme halatının yer ekibine bırakıldığı ve doğrudan geminin ön ucunda bulunan bir platform olan demirleme rafında duruyordu. eksenel yürüme yolu ve 16 numaralı gaz hücresinin hemen önünde. Geri kalanlar ya kontrol arabasının önündeki alt omurga yürüyüş yolu boyunca ya da pruva kıvrımından demirleme rafına giden merdivenin yanındaki platformlarda duruyordu. Yangın sırasında pruva aşağı yukarı 45 derecelik bir açıyla havada asılı kaldı ve alevler eksenel yürüme yolundan fırlayarak pruvadan (ve pruva gaz hücrelerinden) bir kaynak makinesi gibi patladı. Ön bölümden kurtulan üç adam (asansörcü Kurt Bauer, aşçı Alfred Grözinger ve elektrikçi Josef Leibrecht) pruvanın en uzak kıç tarafıydı ve ikisi (Bauer ve Grözinger) iki büyük üçgen havalandırma deliğinin yanında duruyorlardı. ateşin içinden soğuk havanın çekildiği. Bu adamların hiçbiri yüzeysel yanıklardan daha fazla acı çekmedi.[Not 10] Pruva merdiveni boyunca ayakta duran adamların çoğu ya kıç tarafına ateşe düştü ya da havadayken gemiden atlamaya çalıştı. Pruvanın en ucundaki demirleme rafında duran dört adamdan üçü aslında enkazdan canlı olarak çıkarıldı, ancak biri (Erich Spehl, bir arma) kısa bir süre sonra Hava İstasyonu revirinde öldü ve diğer ikisi (dümenci Alfred Bernhard ve çırak asansörcü Ludwig Felber) gazeteler tarafından ilk başta yangından sağ kurtulduklarını ve ardından gece veya ertesi sabah erken saatlerde bölge hastanelerinde öldüğü bildirildi.[kaynak belirtilmeli ]

Hidrojen yangınları, yakın çevreye göre daha az yıkıcıdır. benzin H'nin kaldırma kuvveti nedeniyle patlamalar2sızan kütle atmosferde yükseldikçe yanma ısısının çevresel olarak daha fazla salınmasına neden olan; Hidrojen yangınları, benzin veya odun yangınlarından daha dayanıklıdır.[22] İçindeki hidrojen Hindenburg yaklaşık 90 saniye içinde yandı.

Tutuşma nedeni

Sabotaj hipotezi

Bu bölüm için ek alıntılara ihtiyaç var doğrulama. (Nisan 2009) (Bu şablon mesajını nasıl ve ne zaman kaldıracağınızı öğrenin) |

Felaket anında, sabotaj genellikle yangının sebebi olarak ileri sürülüyordu. Hugo Eckener, Zeppelin Şirketi'nin eski başkanı ve Alman hava gemilerinin "yaşlı adamı". İlk raporlarda, kazayı incelemeden önce Eckener, alınan tehdit mektupları nedeniyle felaketin nedeni olarak bir ateş olasılığından bahsetti, ancak diğer nedenleri ekarte etmedi.[23] Eckener daha sonra statik kıvılcım hipotezini kamuoyuna açıkladı. Avusturya'da bir konferans turu sırasında, sabah saat 2: 30'da (Lakehurst saatiyle 20: 30'da veya kazadan yaklaşık bir saat sonra) başucundaki telefonunun çalmasıyla uyandı. Bir Berlin temsilcisiydi New York Times haberlerle Hindenburg "dün akşam 19: 00'da patladı [sic ] Lakehurst'teki havaalanının yukarısında ". Ertesi sabah felaketle ilgili brifing için Berlin'e gitmek üzere otelden ayrıldığında, kendisini sorgulamak için dışarıda bekleyen muhabirlere vereceği tek cevap, bildiklerine dayalıydı. , Hindenburg "havaalanı üzerinde patladı"; sabotaj bir olasılık olabilir. Bununla birlikte, felaket hakkında daha çok şey öğrendikçe, özellikle de zeplin "patlamaktan" çok yandığını öğrendikçe, sabotajdan ziyade statik boşalmanın neden olduğuna ikna oldu.[24][sayfa gerekli ]

Lakehurst'teki Donanma Hava İstasyonu komutanı Komutan Charles Rosendahl ve geminin kara tabanlı kısmının genel sorumlusu olan adam. Hindenburg's iniş manevrası, aynı zamanda Hindenburg sabote edilmişti. Kitabında sabotaj için genel bir dava açtı Zeplin ne olacak? (1938),[25][sayfa gerekli ] Bu, sert hava gemisinin daha da geliştirilmesi için genişletilmiş bir argüman olduğu kadar, hava gemisi konseptine tarihsel bir bakıştı.

Sabotaj hipotezinin bir başka savunucusu da komutanı Max Pruss'du. Hindenburg zeplin kariyeri boyunca. Pruss neredeyse her uçuşta uçtu Graf Zeppelin e kadar Hindenburg hazırdı. Kenneth Leish tarafından 1960 yılında yapılan bir röportajda Kolombiya Üniversitesi Pruss, Sözlü Tarih Araştırma Ofisi, zeplin seyahat güvenliydi ve bu nedenle sabotajın suçlanacağına şiddetle inanıyordu. Alman turistler için popüler bir destinasyon olan Güney Amerika gezilerinde her iki zeplin de gök gürültülü fırtınalardan geçtiğini ve yıldırım çarptığını ancak zarar görmediğini belirtti.[26]

Mürettebatın çoğu üyesi, zeplin yalnızca bir yolcunun yok edebileceği konusunda ısrar ederek, içlerinden birinin sabotaj eylemi yapacağına inanmayı reddetti. Komutan Rosendahl, Yüzbaşı Pruss ve diğerleri arasında tercih edilen bir şüpheli Hindenburg's mürettebat, yangından kurtulan bir Alman akrobat olan yolcu Joseph Späh'dı. Yanında çocuklarına sürpriz olarak Ulla adlı bir Alman çoban köpeği getirdi. Geminin kıç tarafına yakın bir nakliye odasında tutulmakta olan köpeğini beslemek için bir dizi refakatsiz ziyarette bulunduğu bildirildi. Späh'den şüphelenenler, şüphelerini öncelikle köpeğini beslemek için geminin iç kısmına yapılan yolculuklara dayandırdı, bazı görevlilere göre Späh'in uçuş sırasında Nazi karşıtı şakalar anlattığı, görevliler tarafından Späh'in tekrarlanan gecikmelerden tedirgin göründüğünü hatırladı. inişte ve bir bomba yerleştirmek için zeplin donanımına tırmanabileceği düşünülebilecek bir akrobattı.

1962'de A.A. Hoehling yayınladı Hindenburg'u Kim Yok Etti?sabotaj dışındaki tüm teorileri reddettiği ve bir mürettebat üyesini şüpheli olarak belirlediği. Yangında ölen Hindenburg'da bir hırsız olan Erich Spehl, potansiyel bir sabotajcı olarak adlandırıldı. On yıl sonra, Michael MacDonald Mooney'nin kitabı HindenburgHoehling'in sabotaj hipotezine büyük ölçüde dayanan, Spehl'i olası bir sabotajcı olarak da tanımladı; Mooney'nin kitabı filme alındı Hindenburg (1975). Filmin yapımcıları Hoehling tarafından intihal nedeniyle dava edildi, ancak Hoehling'in davası, sabotaj hipotezini tarihsel gerçek olarak sunduğu için reddedildi ve tarihsel gerçeklerin sahipliğini iddia etmek mümkün değil.[27]

Hoehling, Spehl'i suçlu olarak adlandırırken şunları iddia etti:

- Spehl'in kız arkadaşının komünist inançları ve Nazi karşıtı bağlantıları vardı.

- Yangının kaynağı, geminin genellikle Spehl ve diğer arma arkadaşları dışında kimseye yasak olan bir bölge olan Gas Cell 4'ten geçen podyumun yakınındaydı.

- Hoehling, Baş Komiserin Heinrich Kubis Baş Rigger Ludwig Knorr'un felaketten kısa bir süre önce Cell 4'te hasar gördüğünü söyledi.

- Söylentiler Gestapo 1938'de Spehl'in olası müdahalesini araştırmıştı.

- Spehl'in amatör fotoğrafçılığa olan ilgisi, onu ateşleyici görevi görebilecek flaş ampullerle tanıştırdı.

- Temsilcilerin keşfi New York Polis Departmanı (NYPD) Daha sonra muhtemelen "küçük, kuru bir pilin depolarize edici öğesinden gelen çözünmez kalıntı" olduğu belirlenen bir maddenin Bomba Ekibi. (Hoehling, kuru bir pilin yangın çıkaran bir cihazdaki bir flaş ampulüne güç verebileceğini varsaydı.)

- Tarafından keşif Federal Soruşturma Bürosu (FBI) yangının ilk rapor edildiği 4. ve 5. hücreler arasındaki hava gemisinin valf kapağındaki sarı bir maddenin (FBI) ajanları. Başlangıçta şüphelenilse de kükürt, hidrojeni tutuşturabilen, daha sonra kalıntının aslında bir yangın söndürücü.

- 4. gaz hücresinde, alt yüzgecin yakınındaki mürettebatın yangından hemen önce gördüğü bir parlama veya parlak bir yansıma.

Hoehling'in (ve daha sonra Mooney'nin) hipotezi, Spehl'in insanları öldürmek istemesinin olası olmadığını ve inişten sonra zeplin yanmayı planladığını söylemeye devam ediyor. Bununla birlikte, geminin 12 saatten fazla gecikmesiyle Spehl, bombasının zamanlayıcısını sıfırlamak için bir bahane bulamadı.

Önerildi Adolf Hitler kendisi emretti Hindenburg Eckener'in Nazi karşıtı görüşlerine misilleme olarak imha edilecek.[28]

Hoehling'in kitabının yayınlanmasından bu yana, Dr.Douglas Robinson da dahil olmak üzere çoğu hava gemisi tarihçisi, Hoehling'in sabotaj hipotezini reddetti çünkü onu destekleyecek hiçbir somut kanıt sunulmadı. Hiç bir bomba parçası bulunmadı (ve enkazdan toplanan ve kuru pilden kalıntı olduğu belirlenen numunenin zeplin kıç tarafına yakın herhangi bir yerde bulunduğuna dair mevcut belgelerde hiçbir kanıt yok) ve daha yakın incelendiğinde, Spehl ve kız arkadaşı aleyhindeki delillerin oldukça zayıf olduğu ortaya çıktı. Ek olarak, Rigger Knorr'un Kubis'in iddia ettiği hasarı daha fazla değerlendirmek için 4. hücrede kalması pek olası değildir. TV şovuyla röportajda Sırlar ve Gizemler Hoehling, bunun sadece kendi teorisi olduğunu iddia etti ve ayrıca kısa devrenin yangının başka bir olası nedeni olabileceğini öne sürdü. Ek olarak, Mooney'nin kitabı çok sayıda kurgusal öğeye sahip olduğu için eleştirildi ve arsanın o zamanlar yakında çıkacak olan 1975 filmi için yaratıldığı öne sürüldü.[29] Mooney bunu iddia etse de Luftwaffe memurlar potansiyel bir bomba tehdidini araştırmak için gemideydi, bunu yapmak için gemide olduklarına dair hiçbir kanıt yok ve askeri gözlemciler, zeplin mürettebatının seyir tekniklerini ve hava tahmin uygulamalarını incelemek için önceki uçuşlarda hazır bulundu.[30]

Bununla birlikte, sabotaj hipotezinin muhalifleri, yalnızca spekülasyonun, yangının nedeni olarak sabotajı desteklediğini ve resmi duruşmaların hiçbirinde inandırıcı sabotaj kanıtı üretilmediğini savundu. Erich Spehl yangında öldü ve bu nedenle çeyrek yüzyıl sonra su yüzüne çıkan suçlamaları çürütemedi. FBI, Joseph Späh'ı araştırdı ve Späh'ın bir sabotaj planıyla bağlantısı olduğuna dair hiçbir kanıt bulmadığını bildirdi. Eşi Evelyn'e göre, Späh suçlamalar yüzünden oldukça üzgündü - daha sonra kocasının evinin dışında camları temizlediğini, ilk kez evini sabote ettiğinden şüphelendiğini öğrendiğinde hatırladı. Hindenburgve haber karşısında o kadar şok oldu ki neredeyse durduğu merdivenden düşüyordu.[31]

Ne Alman ne de Amerikan soruşturması sabotaj teorilerinin hiçbirini onaylamadı. Sabotaj hipotezinin savunucuları, herhangi bir sabotaj bulgusunun Nazi rejimi için utanç verici olacağını savunuyorlar ve Alman soruşturmasının böyle bir bulgusunun siyasi nedenlerle bastırıldığını düşünüyorlar. Bununla birlikte, çok sayıda mürettebatın sabotaj hipotezine abone oldukları çünkü zeplin veya pilot hatasıyla ilgili herhangi bir kusuru kabul etmeyi reddettikleri öne sürüldü.[32]

Bazı sansasyonel gazeteler, Luger tabanca Enkazın arasında bir mermi atışı ile bulundu ve gemideki bir kişinin intihar ettiği veya zeplin vurduğu tahmininde bulundu.[33] Bununla birlikte, intihara teşebbüs edildiğini gösteren hiçbir kanıt veya bir Luger tabancasının varlığını doğrulayan resmi bir rapor yoktur.[kaynak belirtilmeli ] Başlangıçta, sahneyi incelemeden önce Eckener, aldıkları tehdit mektupları nedeniyle felaketin nedeni olarak bir çekim olasılığından bahsetti.[23] Alman soruşturmasında Eckener, pek çok olasılığın yanı sıra bir şutu neredeyse imkansız ve son derece olanaksız olduğu gerekçesiyle reddetti.[34]

Statik kıvılcım hipotezi

Bu bölüm için ek alıntılara ihtiyaç var doğrulama. (Mart 2009) (Bu şablon mesajını nasıl ve ne zaman kaldıracağınızı öğrenin) |

Hugo Eckener, yangının bir elektrik kıvılcımı bu, birikmesinden kaynaklandı Statik elektrik zeplin üzerinde.[35] Kıvılcım, dış yüzeyde hidrojeni ateşledi.

Statik kıvılcım hipotezinin savunucuları, zeplin kabuğunun, yükünün gemiye eşit bir şekilde dağılmasına izin verecek şekilde inşa edilmediğine işaret ediyor. Deri ayrıldı duralumin iletken olmayan çerçeve rami iletkenliği iyileştirmek için hafifçe metalle kaplanmış, ancak çok etkili olmayan kablolar, potansiyel cilt ve çerçeve arasında oluşturmak için.

Transatlantik uçuşunda 12 saatten fazla gecikmeyi telafi etmek için, Hindenburg bir havadan geçti ön yüksek nem ve yüksek elektrik yükü. Demirleme halatları ilk yere çarptıklarında ıslak olmamasına ve ateşlemenin dört dakika sonra gerçekleşmesine rağmen, Eckener bu dört dakika içinde ıslanmış olabileceklerini teorize etti. Çerçeveye bağlanan ipler ıslandığında, çerçeveyi topraklayacak, deriyi değil. Bu, deri ve çerçeve arasında (ve üzerini örten hava kütlelerinin bulunduğu zeplin kendisi) arasında ani bir potansiyel farklılığa neden olacak ve bir elektrik boşalmasına neden olacaktı - bir kıvılcım. Topraklamanın en hızlı yolunu arayan kıvılcım, deriden metal iskelete sıçrayarak sızan hidrojeni ateşlerdi.

Kitabında LZ-129 Hindenburg (1964), Zeppelin tarihçisi Dr.Douglas Robinson, serbest hidrojenin statik boşalma yoluyla tutuşmasının tercih edilen bir hipotez haline gelmesine rağmen, 1937'deki kazaya ilişkin resmi soruşturmada ifade veren tanıkların hiçbiri tarafından böyle bir boşalma görülmediğini yorumladı. :

Ancak geçen yıl içinde, şüphesiz New Jersey, Princeton'dan Profesör Mark Heald adında bir gözlemci buldum. Aziz Elmo'nun Ateşi Yangın çıkmadan bir dakika önce hava gemisinin arkasında titriyordu. Standing outside the main gate to the Naval Air Station, he watched, together with his wife and son, as the Zeppelin approached the mast and dropped her bow lines. A minute thereafter, by Mr. Heald's estimation, he first noticed a dim "blue flame" flickering along the backbone girder about one-quarter the length abaft the bow to the tail. There was time for him to remark to his wife, "Oh, heavens, the thing is afire," for her to reply, "Where?" and for him to answer, "Up along the top ridge" – before there was a big burst of flaming hydrogen from a point he estimated to be about one-third the ship's length from the stern.[36]

Unlike other witnesses to the fire whose view of the port side of the ship had the light of the setting sun behind the ship, Professor Heald's view of the starboard side of the ship against a backdrop of the darkening eastern sky would have made the dim blue light of a static discharge on the top of the ship more easily visible.

Harold G. Dick was Goodyear Zeppelin's representative with Luftschiffbau Zeppelin during the mid-1930s. He flew on test flights of the Hindenburg ve onun kardeş gemisi, Graf Zeppelin II. He also flew on numerous flights in the original Graf Zeppelin and ten round-trip crossings of the north and south Atlantic in the Hindenburg. Kitabında The Golden Age of the Great Passenger Airships Graf Zeppelin & Hindenburg, he observes:

There are two items not in common knowledge. When the outer cover of the LZ 130 [the Graf Zeppelin II] was to be applied, the lacing cord was prestretched and run through dope as before but the dope for the LZ 130 contained grafit iletken hale getirmek için. This would hardly have been necessary if the static discharge hypothesis were mere cover-up. The use of graphite dope was not publicized and I doubt if its use was widely known at the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin.

In addition to Dick's observations, during the Graf Zeppelin II's early test flights, measurements were taken of the airship's static charge. Dr. Ludwig Durr and the other engineers at Luftschiffbau Zeppelin took the static discharge hypothesis seriously and considered the insulation of the fabric from the frame to be a design flaw in the Hindenburg. Thus, the German Inquiry concluded that the insulation of the outer covering caused a spark to jump onto a nearby piece of metal, thereby igniting the hydrogen. In lab experiments, using the Hindenburg's outer covering and a static ignition, hydrogen was able to be ignited but with the covering of the LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin, nothing happened. These findings were not well-publicized and were covered up, perhaps to avoid embarrassment of such an engineering flaw in the face of the Third Reich.

A variant of the static spark hypothesis, presented by Addison Bain, is that a spark between inadequately grounded fabric cover segments of the Hindenburg itself started the fire, and that the spark had ignited the "highly flammable" outer skin. Hindenburg had a cotton skin covered with a finish known as "dope". It is a common term for a plastikleştirilmiş cila that provides stiffness, protection, and a lightweight, airtight seal to woven fabrics. In its liquid forms, dope is highly flammable, but the flammability of dry dope depends upon its base constituents, with, for example, butyrate dope being far less flammable than selüloz nitrat. Proponents of this hypothesis claim that when the mooring line touched the ground, a resulting spark could have ignited the dope in the skin.

Bir bölümü Discovery Channel dizi Merak entitled "What Destroyed the Hindenburg?", which first aired in December 2012, investigated both the static spark theory and St. Elmo's Fire, as well as sabotage by bomb. The team, led by British aeronautical engineer Jem Stansfield and US airship historian Dan Grossman, concluded that the ignition took place above the hydrogen vent just forward of where Mark Heald saw St. Elmo's Fire, and that the ignited hydrogen was channelled down the vent where it created a more explosive detonation described by crew member Helmut Lau.

Lightning hypothesis

A. J. Dessler, former director of the Space Science Laboratory at NASA 's Marshall Uzay Uçuş Merkezi and a critic of the incendiary paint hypothesis (see below), favors a much simpler explanation for the conflagration: Şimşek. Like many other aircraft, the Hindenburg had been struck by lightning several times in its years of operation. This does not normally ignite a fire in hydrogen-filled airships due to the lack of oxygen. However, airship fires have been observed when lightning strikes the vehicle as it vents hydrogen as ballast in preparation for landing. The vented hydrogen mixes with the oxygen in the atmosphere, creating a combustible mixture. Hindenburg was venting hydrogen at the time of the disaster.[37]

However, witnesses did not observe any lightning storms as the ship made its final approach.

Engine failure hypothesis

On the 70th anniversary of the accident, Philadelphia Inquirer carried an article[38] with yet another hypothesis, based on an interview of ground crew member Robert Buchanan. He had been a young man on the crew manning the mooring lines.

As the airship was approaching the mooring mast, he noted that one of the engines, thrown into reverse for a hard turn, backfired, and a shower of sparks was emitted. After being interviewed by Addison Bain, Buchanan believed that the airship's outer skin was ignited by engine sparks. Another ground crewman, Robert Shaw, saw a blue ring behind the tail fin and had also seen sparks coming out of the engine.[39] Shaw believed that the blue ring he saw was leaking hydrogen which was ignited by the engine sparks.

Dr. Eckener rejected the idea that hydrogen could have been ignited by an engine geri tepme, postulating that the hydrogen could not have been ignited by any exhaust because the temperature is too low to ignite the hydrogen. The ignition temperature for hydrogen is 500 °C (932 °F), but the sparks from the exhaust only reach 250 °C (482 °F).[32] The Zeppelin Company also carried out extensive tests and hydrogen had never ignited. Additionally, the fire was first seen at the top of the airship, not near the bottom of the hull.

Fire's initial fuel

Most current analyses of the fire assume ignition due to some form of electricity as the cause. However, there is still much controversy over whether the fabric skin of the airship, or the hydrogen used for buoyancy, was the initial fuel for the resulting fire.

Hidrojen hipotezi

The theory that hydrogen was ignited by a static spark is the most widely accepted theory as determined by the official crash investigations. Offering support for the hypothesis that there was some sort of hydrogen leak prior to the fire is that the airship remained stern-heavy before landing, despite efforts to put the airship back in trim. This could have been caused by a leak of the gas, which started mixing with air, potentially creating a form of oksihidrojen gazı and filling up the space between the skin and the cells.[32] A ground crew member, R.H. Ward, reported seeing the fabric cover of the upper port side of the airship fluttering, "as if gas was rising and escaping" from the cell. He said that the fire began there, but that no other disturbance occurred at the time when the fabric fluttered.[32] Another man on the top of the mooring mast had also reported seeing a flutter in the fabric as well.[40] Pictures that show the fire burning along straight lines that coincide with the boundaries of gas cells suggest that the fire was not burning along the skin, which was continuous. Crew members stationed in the stern reported actually seeing the cells burning.[41]

Two main theories have been postulated as to how gas could have leaked. Dr. Eckener believed a snapped bracing wire had torn a gas cell open (see below), while others suggest that a maneuvering or automatic gas valve was stuck open and gas from cell 4 leaked through. During the airship's first flight to Rio, a gas cell was nearly emptied when an automatic valve was stuck open, and gas had to be transferred from other cells to maintain an even keel.[31] However, no other valve failures were reported during the ship's flight history, and on the final approach there was no indication in instruments that a valve had stuck open.[42]

Although proponents of the IPT claim that the hydrogen was odorized with garlic,[43] it would have been detectable only in the area of a leak. Once the fire was underway, more powerful smells would have masked any garlic odor. There were no reports of anyone smelling garlic during the flight, but no official documents have been found to prove that the hydrogen was even odorized.

Opponents of this hypothesis note that the fire was reported as burning bright red, while pure hydrogen burns blue if it is visible at all,[44] although there were many other materials that were consumed by the fire which could have changed its hue.

Some of the airshipmen at the time, including Captain Pruss, asserted that the stern heaviness was normal, since aerodynamic pressure would push rainwater towards the stern of the airship. The stern heaviness was also noticed minutes before the airship made its sharp turns for its approach (ruling out the snapped wire theory as the cause of the stern heaviness), and some crew members stated that it was corrected as the ship stopped (after sending six men into the bow section of the ship). Additionally, the gas cells of the ship were not pressurized, and a leak would not cause the fluttering of the outer cover, which was not seen until seconds before the fire. However, reports of the amount of rain the ship had collected have been inconsistent. Several witnesses testified that there was no rain as the ship approached until a light rain fell minutes before the fire, while several crew members stated that before the approach the ship did encounter heavy rain. Albert Sammt, the ship's first officer who oversaw the measures to correct the stern-heaviness, initially attributed to fuel consumption and sending crewmen to their landing stations in the stern, though years later, he would assert that a leak of hydrogen had occurred. On its final approach the rainwater may have evaporated and may not completely account for the observed stern-heaviness, as the airship should have been in good trim ten minutes after passing through rain. Dr. Eckener noted that the stern heaviness was significant enough that 70,000 kilogram·meter (506,391 foot-pounds) of trimming was needed.[45]

Incendiary paint hypothesis

The incendiary paint theory (IPT) was proposed in 1996 by retired NASA scientist Addison Bain, stating that the doping compound of the airship was the cause of the fire, and that the Hindenburg would have burned even if it were filled with helium. The hypothesis is limited to the source of ignition and to the flame front propagation, not to the source of most of the burning material, as once the fire started and spread the hydrogen clearly must have burned (although some proponents of the incendiary paint theory claim that hydrogen burned much later in the fire or that it otherwise did not contribute to the rapid spread of the fire). The incendiary paint hypothesis asserts that the major component in starting the fire and feeding its spread was the canvas skin because of the compound used on it.

Proponents of this hypothesis argue that the coatings on the fabric contained both iron oxide and aluminum-impregnated cellulose acetate butyrate (CAB) which remain potentially reactive even after fully setting.[46] Iron oxide and aluminum can be used as components of katı roket fuel or termit. Örneğin, propellant for the Space Shuttle solid rocket booster included both "aluminum (fuel, 16%), (and) iron oxide (a katalizör, 0.4%)". The coating applied to the Hindenburg's covering did not have a sufficient quantity of any material capable of acting as an oxidizer,[47] which is a necessary component of rocket fuel,[48] however, oxygen is also available from the air.

Bain received permission from the German government to search their archives and discovered evidence that, during the Nazi regime, German scientists concluded the dope on the Hindenburg's fabric skin was the cause of the conflagration. Bain interviewed the wife of the investigation's lead scientist Max Dieckmann, and she stated that her husband had told her about the conclusion and instructed her to tell no one, presumably because it would have embarrassed the Nazi government.[49] Additionally, Dieckmann concluded that it was the poor conductivity, not the flammability of the doping compound, that led to the ignition of hydrogen.[50] However, Otto Beyersdorff, an independent investigator hired by the Zeppelin Company, asserted that the outer skin itself was flammable. In several television shows, Bain attempted to prove the flammability of the fabric by igniting it with a Yakup'un Merdiveni. Although Bain's fabric ignited, critics argue that Bain had to correctly position the fabric parallel to a machine with a continuous electric current inconsistent with atmospheric conditions. In response to this criticism, the IPT therefore postulates that a spark would need to be parallel to the surface, and that "panel-to-panel arcing" occurs where the spark moves between panels of paint isolated from each other. A.J. Dessler, a critic of the IPT, points out a static spark does not have sufficient energy to ignite the doping compound, and that the insulating properties of the doping compound prevents a parallel spark path through it. Additionally, Dessler contends that the skin would also be electrically conductive in the wet and damp conditions before the fire.[51]

Critics also argue that port side witnesses on the field, as well as crew members stationed in the stern, saw a glow inside Cell 4 before any fire broke out of the skin, indicating that the fire began inside the airship or that after the hydrogen ignited, the invisible fire fed on the gas cell material. Newsreel footage clearly shows that the fire was burning inside the structure.[31]

Proponents of the paint hypothesis claim that the glow is actually the fire igniting on the starboard side, as seen by some other witnesses. From two eyewitness statements, Bain asserts the fire began near cell 1 behind the tail fins and spread forward before it was seen by witnesses on the port side. However, photographs of the early stages of the fire show the gas cells of the Hindenburg's entire aft section fully aflame, and no glow is seen through the areas where the fabric is still intact. Burning gas spewing upward from the top of the airship was causing low pressure inside, allowing atmospheric pressure to press the skin inwards.

Bazen Hindenburg's varnish is incorrectly identified as, or stated being similar to, selüloz nitrat which, like most nitrates, burns very readily.[28] Instead, the cellulose acetate butyrate (CAB) used to seal the zeppelin's skin is rated by the plastics industry as combustible but nonflammable. That is, it will burn if placed within a fire but is not readily ignited. Not all fabric on the Hindenburg burned.[52] For example, the fabric on the port and starboard tail fins was not completely consumed. That the fabric not near the hydrogen fire did not burn is not consistent with the "explosive" dope hypothesis.

TV programı Efsane Avcıları explored the incendiary paint hypothesis. Their findings indicated that the aluminum and iron oxide ratios in the Hindenburg's skin, while certainly flammable, were not enough on their own to destroy the zeppelin. Had the skin contained enough metal to produce pure thermite, the Hindenburg would have been too heavy to fly. The MythBusters team also discovered that the Hindenburg's coated skin had a higher ignition temperature than that of untreated material, and that it would initially burn slowly, but that after some time the fire would begin to accelerate considerably with some indication of a thermite reaction. From this, they concluded that those arguing against the incendiary paint theory may have been wrong about the airship's skin not forming thermite due to the compounds being separated in different layers. Despite this, the skin alone would burn too slowly to account for the rapid spread of the fire, as it would have taken four times the speed for the ship to burn. The MythBusters concluded that the paint may have contributed to the disaster, but that it was not the sole reason for such rapid combustion.[53]

Puncture hypothesis

Although Captain Pruss believed that the Hindenburg could withstand tight turns without significant damage, proponents of the puncture hypothesis, including Hugo Eckener, question the airship's structural integrity after being repeatedly stressed over its flight record.

The airship did not receive much in the way of routine inspections even though there was evidence of at least some damage on previous flights. It is not known whether that damage was properly repaired or even whether all the failures had been found. During the ship's first return flight from Rio, Hindenburg had once lost an engine and almost drifted over Africa, where it could have crashed. Afterwards, Dr. Eckener ordered section chiefs to inspect the airship during flight. However, the complexity of the airship's structure would make it virtually impossible to detect all weaknesses in the structure. Mart 1936'da Hindenburg ve Graf Zeppelin yapılmış three-day flights to drop leaflets and broadcast speeches via hoparlör. Before the airship's takeoff on March 26, 1936, Ernst Lehmann chose to launch the Hindenburg with the wind blowing from behind the airship, instead of into the wind as per standard procedure. During the takeoff, the airship's tail struck the ground, and part of the lower fin was broken.[54] Although that damage was repaired, the force of the impact may have caused internal damage. Only six days before the disaster, it was planned to make the Hindenburg have a hook on her hull to carry aircraft, similar to the US Navy's use of the USS Akron ve USS Macon hava gemileri. However, the trials were unsuccessful as the biplane hit the Hindenburg's trapeze several times. The structure of the airship may have been further affected by this incident.

Newsreels, as well as the map of the landing approach, show the Hindenburg made several sharp turns, first towards port and then starboard, just before the accident. Proponents posit that either of these turns could have weakened the structure near the vertical fins, causing a bracing wire to snap and puncture at least one of the internal gas cells. Additionally, some of the bracing wires may have even been substandard. One bracing wire tested after the crash broke at a mere 70% of its rated load.[31] A punctured cell would have freed hydrogen into the air and could have been ignited by a static discharge (see above), or it is also possible that the broken bracing wire struck a girder, causing sparks to ignite hydrogen.[31] When the fire started, people on board the airship reported hearing a muffled detonation, but outside, a ground crew member on the starboard side reported hearing a crack. Some speculate the sound was from a bracing wire snapping.[31]

Eckener concluded that the puncture hypothesis, due to pilot error, was the most likely explanation for the disaster. He held Captains Pruss and Lehmann, and Charles Rosendahl responsible for what he viewed as a rushed landing procedure with the airship badly out of trim under poor weather conditions. Pruss had made the sharp turn under Lehmann's pressure; while Rosendahl called the airship in for landing, believing the conditions were suitable. Eckener noted that a smaller storm front followed the thunderstorm front, creating conditions suitable for static sparks.

During the US inquiry, Eckener testified that he believed that the fire was caused by the ignition of hydrogen by a static spark:

The ship proceeded in a sharp turn to approach for its landing. That generates extremely high tension in the after part of the ship, and especially in the center sections close to the stabilizing fins which are braced by shear wires. I can imagine that one of these shear wires parted and caused a rent in a gas cell. If we will assume this further, then what happened subsequently can be fitted in to what observers have testified to here: Gas escaped from the torn cell upwards and filled up the space between the outer cover and the cells in the rear part of the ship, and then this quantity of gas which we have assumed in the hypothesis was ignited by a static spark.

Under these conditions, naturally, the gas accumulated between the gas cells and the outer cover must have been a very rich gas. That means it was not an explosive mixture of hydrogen, but more of a pure hydrogen. The loss of gas must have been appreciable.

I would like to insert here, because the necessary trimming moments to keep the ship on an even keel were appreciable, and everything apparently happened in the last five or six minutes, that is, during the sharp turn preceding the landing maneuver, that therefore there must have been a rich gas mixture up there, or possibly pure gas, and such gas does not burn in the form of an explosion. It burns off slowly, particularly because it was in an enclosed space between outer cover and gas cells, and only in the moment when gas cells are burned by the burning off of this gas, then the gas escapes in greater volume, and then the explosions can occur, which have been reported to us at a later stage of the accident by so many witnesses.

The rest it is not necessary for me to explain, and in conclusion, I would like to state this appears to me to be a possible explanation, based on weighing all of the testimony that I have heard so far.[55]

However, the apparent stern heaviness during the landing approach was noticed thirty minutes before the landing approach, indicating that a gas leak resulting from a sharp turn did not cause the initial stern heaviness.[55]

Yakıt sızıntısı

2001 belgeseli Hindenburg Disaster: Probable Cause suggested that 16-year-old Bobby Rutan, who claimed that he had smelled "gasoline" when he was standing below the Hindenburg's aft port engine, had detected a diesel fuel leak. During the investigation, Commander Charles Rosendahl dismissed the boy's report. The day before the disaster, a fuel pump had broken during the flight, but the chief engineer testified that the pump had been replaced. The resulting vapor of a diesel leak, in addition to the engines being overheated, would have been highly flammable and could have self-combusted.

However, the documentary makes numerous mistakes into assuming that the fire began in the keel. First, it implies that the crewmen in the lower fin had seen the fire start in the keel and that Hans Freund and Helmut Lau looked towards the front of the airship to see the fire, when Freund was actually looking rearward when the fire started. Most witnesses on the ground reported seeing flames at the top of the ship, but the only location where a fuel leak could have a potential ignition source is the engines. Additionally, while investigators in the documentary suggest it is possible for a fire in the keel to go unnoticed until it breaks the top section, other investigators such as Greg Feith consider it unlikely because the only point diesel comes into contact with a hot surface is the engines.

Rate of flame propagation

Regardless of the source of ignition or the initial fuel for the fire, there remains the question of what caused the rapid spread of flames along the length of the airship, with debate again centered on the fabric covering of the airship and the hydrogen used for buoyancy.

Proponents of both the incendiary paint hypothesis and the hydrogen hypothesis agree that the fabric coatings were probably responsible for the rapid spread of the fire. The combustion of hydrogen is not usually visible to the human eye in daylight, because most of its radiation is not in the visible portion of the spectrum but rather ultraviolet. Thus what can be seen burning in the photographs cannot be hydrogen. However, black-and-white photographic film of the era had a different light sensitivity spectrum than the human eye, and was sensitive farther out into the infrared and ultraviolet regions than the human eye. While hydrogen tends to burn invisibly, the materials around it, if combustible, would change the color of the fire.

The motion picture films show the fire spreading downward along the skin of the airship. While fires generally tend to burn upward, especially including hydrogen fires, the enormous radiant heat from the blaze would have quickly spread fire over the entire surface of the airship, thus apparently explaining the downward propagation of the flames. Falling, burning debris would also appear as downward streaks of fire.

Those skeptical of the incendiary paint hypothesis cite recent technical papers which claim that even if the airship had been coated with actual rocket fuel, it would have taken many hours to burn – not the 32 to 37 seconds that it actually took.[56]

Modern experiments that recreated the fabric and coating materials of the Hindenburg seem to discredit the incendiary fabric hypothesis.[57] They conclude that it would have taken about 40 hours[açıklama gerekli ] için Hindenburg to burn if the fire had been driven by combustible fabric. Two additional scientific papers also strongly reject the fabric hypothesis.[56][açıklama gerekli ] Ancak Efsane Avcıları Hindenburg special seemed to indicate that while the hydrogen was the dominant driving force the burning fabric doping was significant with differences in how each burned visible in the original footage.

The most conclusive[açıklama gerekli ] proof against the fabric hypothesis is in the photographs of the actual accident as well as the many airships which were not doped with aluminum powder and still exploded violently. When a single gas cell explodes, it creates a shock wave and heat. The shock wave tends to rip nearby bags which then explode themselves. In the case of the Ahlhorn disaster on January 5, 1918, explosions of airships in one hangar caused the explosions of others in three adjoining hangars, wiping out all five Zeppelins at the base.[açıklama gerekli ]

The photos of the Hindenburg disaster clearly show that after the cells in the aft section of the airship exploded and the combustion products were vented out the top of the airship, the fabric on the rear section was still largely intact, and air pressure from the outside was acting upon it, caving the sides of the airship inward due to the reduction of pressure caused by the venting of combustion gases out the top.

The loss of lift at the rear caused the airship to nose up suddenly and the back to break in half (the airship was still in one piece), at that time the primary mode for the fire to spread was along the axial gangway which acted as a chimney, conducting fire which burst out the nose as the airship's tail touched the ground, and as seen in one of the most famous pictures of the disaster.

anıt

The actual site of the Hindenburg crash is at Naval Air Station Lakehurst, renamed by the Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR) as Naval Air Engineering Station (NAES) Lakehurst (or "Navy Lakehurst" for short).[58] It is marked with a chain-outlined pad and bronze plaque where the airship's gondola landed.[59] It was dedicated on May 6, 1987, the 50th anniversary of the disaster.[60] Hangar 1, which still stands, is where the airship was to be housed after landing. It was designated a Registered National Historic Landmark in 1968.[61] Pre-registered tours are held through the Navy Lakehurst Historical Society.[60]

Ayrıca bakınız

- Kilitlenme kapağı

- Hindenburg disaster in popular culture

- Hindenburg disaster newsreel footage

- Hindenburg: Anlatılmayan Hikaye, bir belgesel dram aired on the 70th anniversary of the disaster, May 6, 2007

- Albert Sammt

- Hidrojen teknolojilerinin zaman çizelgesi

Referanslar

Notlar

- ^ Per an annotated ship's diagram submitted to the U.S. Commerce Department's Board of Inquiry into the disaster, there were 12 men in the forward section of the ship at the time of the fire: Ludwig Felber (apprentice "elevatorman"); Alfred Bernhardt (helmsman); Erich Spehl (rigger); Ernst Huchel (senior elevatorman); Rudi Bialas (engine mechanic); Alfred Stöckle (engine mechanic); Fritz Flackus (cook's assistant); Richard Müller (cook's assistant); Ludwig Knorr (chief rigger); Josef Leibrecht (electrician); Kurt Bauer (elevatorman); and Alfred Grözinger (cook). Of these, only Leibrecht, Bauer and Grözinger survived the fire. Examination of the unedited Board of Inquiry testimony transcripts (stored at the National Archives), combined with a landing stations chart in Dick & Robinson (1985, s. 212) indicates that the six off-watch men who were sent forward to trim the ship were Bialas, Stöckle, Flackus, Müller, Leibrecht and Grözinger. The other men were at their previously assigned landing stations. Daha yeni araştırmalar[Kim tarafından? ] found that was not Bialas, but his colleague Walter Banholzer, who was sent forward along with the other five men.

- ^ Birger Brinck, Burtis John Dolan, Edward Douglas, Emma Pannes, Ernst Rudolf Anders, Fritz Erdmann, Hermann Doehner, John Pannes, Moritz Feibusch, Otto Reichold.

- ^ Albert Holderried, mechanic; Alfred Stockle, engine mechanic; Alois Reisacher, mechanic; Emilie Imohof, hostess; Ernst Huchel, senior elevatorman; Ernst Schlapp, electrician; Franz Eichelmann, radio operator; Fritz Flackus, cook's assistant; Alfred Hitchcok, chief mechanic; Ludwig Knorr, chief rigger; Max Schulze, bar steward; Richard Muller, assistant chef; Robert Moser, mechanic; Rudi Bialas, engine mechanic; Wilhelm Dimmler, engineering officer; Willi Scheef, mechanic.

- ^ Some of the 26 people listed as immediate victims may have actually died immediately after the disaster in the air station's infirmary, but being identified only after some time, along with the corpses of the victims who died in the fire.

- ^ Alfred Bernhardt, helmsman; Erich Spehl, rigger; Ernst August Lehmann, director of flight operations; Ludwig Felber, apprentice elevatorman; Walter Banholzer, engine mechanic; Willy Speck, chief radio operator.

- ^ Erich Knocher, Irene Doehner, and Otto Ernst.

- ^ This is corroborated by the official testimonies and later recollections of several passenger survivors from the starboard passenger deck, including Nelson Morris, Leonhard Adelt and his wife Gertrud, Hans-Hugo Witt, Rolf von Heidenstam, and George Hirschfeld.

- ^ Board of Inquiry testimony of Hans-Hugo Witt, a Luftwaffe military observer traveling as a passenger.

- ^ Subsequent on-camera interviews with Späh and his letter to the Board of Inquiry corroborate this version of his escape. One or two more dramatic versions of his escape have appeared over the years, neither of which are supported by the newsreels of the crash, one of which shows a fairly close view of the portside passenger windows as passengers and stewards begin to drop through them.

- ^ Board of Inquiry testimonies of Kurt Bauer and Alfred Grözinger

Alıntılar

- ^ WLS Broadcast Of the Hindenburg Disaster 1937. Chicagoland Radio and Media Erişim tarihi: May 7, 2015

- ^ Craats 2009, s. 36.

- ^ "Airplane shuttle service to operate, Newark to Lakehurst, for Hindenburg." New York Times, 12 Nisan 1936. s. XX5.

- ^ a b Blackwell 2007, s. 311.

- ^ Hoffmann & Harkin 2002, s. 235.

- ^ Mooney 1972, s. 262.

- ^ The full recording is available at “Hindenburg Disaster: Herb Morrison Reporting,” Radio Days, www.otr.com/hindenburg.shtml (accessed May 21, 2014).

- ^ "Herb Morrison - Hindenburg Disaster, 1937". Ulusal Arşiv.

- ^ Fielding, Raymond "The American Newsreel: A Complete History, 1911–1967, 2d ed." Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., (2006) pp. 142–3

- ^ "How Did They Ever Get That" Photoplay Magazine, October 1937, p.24

- ^ "Life on the American Newsfront: Amateur Photographs of the Hindenburg's Last Landing". LIFE Dergisi. May 17, 1937.

- ^ Russell, Patrick (May 6, 2015). "Hindenburg Crash – Foo Chu's Amateur Photo Sequence". Projekt LZ 129. Alındı 2 Haziran, 2017.

- ^ John Duggan and Henry Cord Meyer (2001). Airships in International Affairs, 1890–1940. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0333751282.CS1 Maint: yazar parametresini kullanır (bağlantı)

- ^ Russell, Patrick. "Allen Orlando Hagaman (1885–1937)". Projekt LZ129. Alındı 29 Temmuz 2015.

- ^ Russell, Patrick B. "Passengers aboard LZ 129 Hindenburg – May 3–6, 1937." Faces of The Hindenburg, October 25, 2009. Retrieved: April 7, 2012.

- ^ Grossman, Dan. "The Hindenburg Disaster". Airships.net. Alındı 29 Temmuz 2015.

- ^ Weber, Bruce. "Werner Franz, survivor of the Hindenburg's crew, dies at 92." New York Times, August 29, 2014.

- ^ a b McCormack, Kathy (November 15, 2019). "Last survivor of the Hindenburg disaster dies at age 90". AP. Alındı 16 Kasım 2019 – via MSN.con.

- ^ Frassanelli, Mike "The Hindenburg 75 years later: Memories time cannot erase." Newark Yıldız Defteri, 6 Mayıs 2012.

- ^ "Faces of the Hindenburg Captain Max Pruss". December 6, 2008.

- ^ Russell, Patrock. "Captain Ernst A. Lehmann". Faces of the Hindenburg. Alındı 29 Temmuz 2015.

- ^ Werthmüller, Andreas. The Hindenburg Disaster. Rüfenacht Switzerland: Swiss Hydrogen Association, February 22, 2006. Arşivlendi 10 Şubat 2008, Wayback Makinesi

- ^ a b "Zeppelin plot a possibility, Eckener says." The Pittsburgh Press, May 7, 1937, p. 20.

- ^ Eckener, Hugo. My Zeppelins. New York: Putnam & Co. Ltd., 1958.

- ^ Rosendahl, Commander C.E. What About The Airship?. New York: Charles Scribner'ın Oğulları, 1938.

- ^ "Max Pruss." Columbia University's Oral History Research Office interview. Retrieved: September 20, 2010.Arşivlendi 8 Haziran 2011, Wayback Makinesi

- ^ "Hoehling."law.uconn.edu. Retrieved: September 20, 2010.Arşivlendi 24 Eylül 2006, Wayback Makinesi

- ^ a b National Geographic 2000.

- ^ Russell, Patrick. "Erich Spehl". Faces of the Hindenburg. Alındı 20 Ekim 2015.

- ^ Russell, Patrick. "Colonel Fritz Erdmann". Faces of the Hindenburg. Alındı 20 Ekim 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Hindenburg Disaster: Probable Cause. Moondance Films (2001), also known as Revealed... The Hindenburg Mystery (2002)

- ^ a b c d "Hindenburg: The Untold Story." Arşivlendi 16 Nisan 2015, Wayback Makinesi Smithsonian Kanalı, broadcast date: May 6, 2007 6.00 pm. Erişim: 5 Nisan 2015.

- ^ Archbold 1994; Toland 1972, s. 337.

- ^ The Sunday Morning Star (23 Mayıs 1937). "Eckener patlamayı çözmeye çalışıyor". s. 6.

- ^ "Secrets of the Dead: PBS television documentary on the Hindenburg disaster." pbs.org. Retrieved: September 20, 2010.

- ^ Robinson, Douglas. LZ-129 Hindenburg. New York: Arco Publishing Co, 1964.

- ^ Dessler, A. J. (June 2004). "The Hindenburg Hydrogen Fire: Fatal Flaws in the Addison Bain Incendiary-Paint Theory" (PDF). Colorado Boulder Üniversitesi.

- ^ "The real cause of the Hindenburg disaster?" Philadelphia Inquirer, May 6, 2007. Arşivlendi 29 Eylül 2007, Wayback Makinesi

- ^ "Hindenburg." Arşivlendi 27 Mayıs 2008, Wayback Makinesi balloonlife.com. Retrieved: September 20, 2010.

- ^ Botting 2001, sayfa 249–251.

- ^ "Thirty-two Seconds." keepgoing.org. Retrieved: September 20, 2010.

- ^ Dick & Robinson 1985, s. 148.

- ^ Stromberg, Joseph (May 10, 2012). "Hindenburg Felaketini Gerçekte Ne Ateşledi?". smithsonianmag.com. Paragraf 6. Alındı 23 Ekim 2015.

Asilzade, Marc Tyler (2006). Hindenburg. Minneapolis, MN: Compass Point Books. s. 38. - ^ Kral İvan R .; Bedin, Luigi R .; Piotto, Giampaolo; Cassisi, Santi; Anderson, Jay (Ağustos 2005). "Hidrojen Yakma Sınırına Kadar Renk Büyüklüğü Diyagramları ve Parlaklık Fonksiyonları. III. NGC 6791'in Hubble Uzay Teleskopu Ön Çalışması". Astronomical Journal. 130 (2): 626–634. arXiv:astro-ph / 0504627. Bibcode:2005AJ .... 130..626K. doi:10.1086/431327.

- ^ "Hindenburg Kaza Raporu: ABD Ticaret Bakanlığı". airships.net. Alındı 20 Eylül 2010.

Amerika Birleşik Devletleri Ticaret Bakanlığı tarafından yayınlanan 15 Ağustos 1937 tarihli Hava Ticaret Bülteninden (cilt 9, no. 2) alınmıştır.

- ^ Bain, A .; Van Vorst, W.D. (1999). "Hindenburg trajedisi yeniden ziyaret edildi: Ölümcül kusur bulundu". Uluslararası Hidrojen Enerjisi Dergisi. 24 (5): 399–403. doi:10.1016 / S0360-3199 (98) 00176-1.

- ^ "Hindenburg örtüsüne uygulanan uyuşturucu tartışması." airships.net. Erişim: 20 Eylül 2010.

- ^ "Roket yakıtının tanımı." Arşivlendi 28 Temmuz 2009, at Wayback Makinesi nasa.gov. Erişim: 20 Eylül 2010.

- ^ "Hindenburg'a Ne Oldu?" PBS, 15 Haziran 2001.

- ^ Archbold 1994.

- ^ Dessler, A.J. "Hindenburg Hidrojen Yangını: Addison Bain Yangın Çıkarıcı Boya Teorisinde Ölümcül Kusurlar" (PDF). Alındı 29 Temmuz 2015.

- ^ "Hindenburg Örtüsünün Yanıcılığı." airships.net. Erişim: 20 Eylül 2010.

- ^ "MythBusters 70.Bölüm" Discovery Channel, ilk yayın, 10 Ocak 2007. Erişim: 3 Mayıs 2009.

- ^ "WSU Özel Koleksiyonları: Harold G. Dick Sergisi". specialcollections.wichita.edu. Wichita Eyalet Üniversite Kütüphaneleri. Alındı 20 Eylül 2010.

- ^ a b Russell, Patrick (11 Ocak 2013). "Das ich nicht ...". Projekt LZ129. Alındı 26 Temmuz 2015.

- ^ a b "Hindenburg yangın teorileri." spot.colorado.edu. Erişim: 20 Eylül 2010.

- ^ "Yanıcı kaplama (IPT) üzerine Yurttaş Bilim Adamı." sas.org. Erişim: 20 Eylül 2010. Arşivlendi 1 Haziran 2009, Wayback Makinesi

- ^ "Lakehurst". lakehust.navy.mil. Arşivlenen orijinal 14 Eylül 2008. Alındı 20 Eylül 2010.

- ^ "Hindenburg'un Kaza Yeri". roadideamerica.com. Alındı 20 Eylül 2010.

- ^ a b "Turlar". hlhs.com. Navy Lakehurst Tarih Kurumu. Alındı 20 Eylül 2010.

- ^ "NAVAIR Lakehurst Bilgi Sayfası". 198.154.24.34/nlweb/. Arşivlenen orijinal 29 Eylül 2007. Alındı 20 Eylül 2010.

Kaynakça

- Archbold Rick (1994). Hindenburg: Resimli Bir Tarih. Toronto: Viking Stüdyosu / Madison Press. ISBN 0-670-85225-2.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Birchall, Frederick (1 Ağustos 1936). "100.000 Hail Hitler; ABD Sporcuları Ona Nazilerin Selamını Vermekten Kaçının". New York Times. s. 1.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Blackwell Jon (2007). Notorious New Jersey: 100 True Tales of Murders and Mobsters, Skandallar ve Alçaklar. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-4177-8.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Botting, Douglas (2001). Dr.Eckener'ın Rüya Makinesi: Büyük Zeplin ve Hava Yolculuğunun Şafağı. New York: Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-6458-3.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Craats, Rennay (2009). ABD: Geçmiş, Bugün, Gelecek-Ekonomi. New York: Weigl Yayıncıları. ISBN 978-1-60596-247-4.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Deutsche Zeppelin-Reederei (1937). Hava Gemisi Yolculukları Kolaylaştı ("Hindenburg" yolcuları için 16 sayfalık kitapçık). Friedrichshafen, Almanya: Luftschiffbau Zeppelin G.m.b.H.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Dick, Harold G .; Robinson, Douglas H. (1985). Büyük Yolcu Hava Gemilerinin Altın Çağı Graf Zeppelin ve Hindenburg. Washington, D.C. ve Londra: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-56098-219-5.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Duggan, John (2002). LZ 129 "Hindenburg": Tüm Hikaye. Ickenham, İngiltere: Zeppelin Çalışma Grubu. ISBN 0-9514114-8-9.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Hoehling, A.A (1962). Hindenburg'u Kim Yok Etti?. Boston: Little, Brown ve Company. ISBN 0-445-08347-6.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Hoffmann, Peter; Harkin, Tom (2002). Yarının Enerjisi. Boston: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-58221-6.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Lehmann Ernst (1937). Zeppelin: Havadan Hafif Geminin Hikayesi. Londra: Longmans, Green and Co.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Majoor, Mireille (2000). Hindenburg'un içinde. Boston: Little, Brown ve Company. ISBN 0-316-12386-2.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Mooney, Michael Macdonald (1972). Hindenburg. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. ISBN 0-396-06502-3.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- National Geographic (2000). Hindenburg'un Ateşli Sırrı (DVD). Washington, D.C .: National Geographic Videosu.

- Toland, John (1972). Büyük Dirigibles: Zaferleri ve Felaketleri. Boston: Courier Dover Yayınları. ISBN 978-0-486-21397-2.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

daha fazla okuma

- Lawson, Don. Mühendislik Felaketleri: Alınacak Dersler. New York: ASME Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0791802304.

Dış bağlantılar

Video

- Gerçek film görüntüleri Hindenburg felaket

- Kısa film Hindenburg Patlar (1937) adresinden ücretsiz olarak indirilebilir İnternet Arşivi

- Kısa film Hindenburg Crash, 5 Haziran 1937 (Disk 2) (1937) adresinden ücretsiz olarak indirilebilir İnternet Arşivi

- Kısa film Evrensel Haber Filmi Özel Yayın - Zeplin Patladı Skorları Ölü, 1937/05/10 (1937) adresinden ücretsiz olarak indirilebilir İnternet Arşivi

- YouTube videosu: Universal Newsreel - 10 Mayıs 1937 Hindenburg felaket.

- Herb Morrison'un ünlü raporunun YouTube videosu, haber filmi çekimleriyle senkronize edildi

Makaleler ve raporlar

- Hindenburg felaket - Orijinal raporlar Kere (Londra)

- Hindenburg Lakehurst'ta Son Durmasını Sağlıyor – Hayat 1937 tarihli dergi makalesi

- Hindenburg Felaket - FBI soruşturmasının raporu

- Hindenburg 75 yıl sonra: Anılar zamanı silemez - NJ.com/Star-Ledger 75. yıldönümü ile ilgili makale Hindenburg felaket

- Radyo Hızlı Zeplin Kapsamı Sağlıyor – Yayın Dergi. s. 14. (15 Mayıs 1937) radyonun Hindenburg felaket

- Ateş altında! - WLS Yanında olmak dergisi (15 Mayıs 1937) Herb Morrison ve mühendisi Charlie Nehlsen hakkındaki makale Hindenburg felaket

Web siteleri

- Roket Yakıtı, Termit ve Hidrojen: Hindenburg Crash

- Airships.net: Tartışma Hindenburg Crash

- "Hindenburg & Hidrojen " yazan: Dr.Karl Kruszelnicki

- Hindenburg ve Hidrojen: Dr.Karl Kruszelnicki'den Saçma - Önceki makaleye bir çürütme

- Otuz iki saniye - Felaketin nadir fotoğraflarını, hayatta kalan mürettebatın bir fotoğrafını ve Cabin Boy Werner Franz hakkında bir raporu içeren makale

- "Ne oldu Hindenburg?" Transcript: Ölülerin Sırları (15 Haziran 2001, PBS)

- "Yolcu ve Mürettebat Listesi Hindenburg son yolculuğunda ". Arşivlenen orijinal 18 Aralık 2013. Alındı 30 Haziran, 2008.

- Yüzleri Hindenburg: Hayatta kalanların ve son yolculuğun kurbanlarının biyografileri ve fotoğrafları

Yanıcı kumaş afet hipotezi

- "Yanıcı Kumaş Hipotezini Destekleyen Bir Makale". Arşivlenen orijinal 2 Aralık 2002. Alındı 30 Haziran, 2008.

- Yanıcı Kumaş Hipotezini Reddeden İki Makale

- "Motor egzoz kıvılcımı hipotezini destekleyen bir makale". 29 Eylül 2007 tarihinde orjinalinden arşivlendi. Alındı 30 Haziran, 2008.CS1 bakimi: BOT: orijinal url durumu bilinmiyor (bağlantı)