Üç yaş sistemi - Three-age system - Wikipedia

üç yaş sistemi tarihin üç zaman dilimine bölünmesidir;[1][daha iyi kaynak gerekli ]örneğin: Taş Devri, Bronz Çağı, ve Demir Çağı; aynı zamanda tarihsel zaman dönemlerinin diğer üçlü bölümlerine de atıfta bulunmasına rağmen. Tarihte, arkeoloji ve fiziksel antropoloji Üç yaş sistemi, 19. yüzyılda benimsenen, tarih öncesi ve erken tarihe ait eserlerin ve olayların tanınabilir bir kronolojiye göre sıralanabileceği metodolojik bir kavramdır. Başlangıçta tarafından geliştirilmiştir C. J. Thomsen müdürü İskandinav Eski Eserler Kraliyet Müzesi Kopenhag, eserlerin yapılıp yapılmadığına göre müzenin koleksiyonlarını sınıflandırmanın bir yolu olarak taş, bronz veya Demir.

Sistem ilk olarak bilim alanında çalışan İngiliz araştırmacılara başvurdu. etnoloji İngiltere'nin geçmişine dayalı yarış dizileri oluşturmak için onu benimseyen kafatası türleri. İlk bilimsel bağlamını oluşturan kranyolojik etnolojinin hiçbir bilimsel değeri olmamasına rağmen, göreceli kronoloji of Taş Devri, Bronz Çağı ve Demir Çağı hala genel bir kamusal bağlamda kullanılıyor,[2][3] ve üç çağ, Avrupa, Akdeniz dünyası ve Yakın Doğu için tarih öncesi kronolojinin temelini oluşturuyor.[4]

Yapı, Akdeniz, Avrupa ve Orta Doğu'nun kültürel ve tarihi geçmişini yansıtıyor ve kısa süre sonra 1865'te Taş Devri'nin bölünmesi dahil olmak üzere başka alt bölümlere girdi. Paleolitik, Mezolitik ve Neolitik dönemler John Lubbock.[5] Bununla birlikte, Sahra altı Afrika'da, Asya'nın çoğunda, Amerika'da ve diğer bazı bölgelerde kronolojik çerçevelerin kurulması için çok az faydası vardır veya hiç faydası yoktur ve bu bölgeler için çağdaş arkeolojik veya antropolojik tartışmalarda çok az önemi vardır.[6]

Menşei

Tarih öncesi çağları metallere dayalı sistemlere ayırma kavramı Avrupa tarihinde çok eskilere uzanır ve muhtemelen Lucretius MÖ birinci yüzyılda. Ancak üç ana çağın (taş, bronz ve demir) mevcut arkeolojik sistemi Danimarkalı arkeologdan kaynaklanmaktadır. Christian Jürgensen Thomsen (1788–1865), sistemi ilk başta araçların ve diğerlerinin tipolojik ve kronolojik çalışmalarıyla daha bilimsel bir temele oturtan eserler Kopenhag'daki Kuzey Eski Eserler Müzesi'nde sergileniyor (daha sonra Danimarka Ulusal Müzesi ).[7] Daha sonra, kontrollü kazılar yapan Danimarkalı arkeologlar tarafından yayınlanan veya kendisine gönderilen kazı raporlarını ve eserleri kullandı. Müzenin küratörü olarak konumu, ona Danimarka arkeolojisi üzerinde oldukça etkili olması için yeterli görünürlük sağladı. Tanınmış ve sevilen bir şahsiyet olarak, çoğu profesyonel arkeolog olan müzedeki ziyaretçilere kendi sistemini bizzat anlattı.

Hesiod'un Metalik Çağları

Şiirinde İşler ve Günler, Antik Yunan şair Hesiod muhtemelen MÖ 750 ile 650 arasında, birbirini izleyen beş tanımlanmış İnsan Yaşları: 1. Altın, 2. Gümüş, 3. Bronz, 4. Kahraman ve 5. Demir.[8] Yalnızca Bronz Çağı ve Demir Çağı metal kullanımına dayanmaktadır:[9]

... sonra baba Zeus üçüncü nesil ölümlüleri yarattı, bronz çağı ... Korkunç ve güçlüydüler ve Ares'in korkunç eylemi onlara aitti ve şiddet. ... Bu adamların silahları bronz, evleri bronzdu ve bronz ustası olarak çalışıyorlardı. Henüz siyah demir yoktu.

Hesiod, geleneksel şiirden biliyordu. İlyada ve alet ve silah yapmak için demirin kullanılmasından önce bronzun tercih edilen malzeme olduğu ve demirin hiç eritilmediği Yunan toplumunda bol miktarda bulunan yadigarı bronz eserler. Üretim metaforuna devam etmedi, ancak metaforlarını karıştırarak her metalin piyasa değerine geçti. Demir bronzdan daha ucuzdu, bu yüzden altın ve gümüş bir çağ olmalı. Bir dizi metalik çağ tasvir ediyor, ancak bu bir ilerlemeden ziyade bir bozulmadır. Her çağ, öncekinden daha az ahlaki değere sahiptir.[10] Kendi çağından diyor ki:[11] "Ve keşke beşinci nesil insanlardan biri olmasaydım, ama gelmeden önce ölmüş olsaydım ya da daha sonra doğmuş olsaydım."

Lucretius'un Gelişimi

Metal çağlarının ahlaki metaforu devam etti. Lucretius ancak ahlaki bozulmanın yerini ilerleme kavramı aldı,[12] bireysel bir insanın büyümesi gibi olduğunu düşündü. Kavram evrimseldir:[13]

Çünkü bir bütün olarak dünyanın doğası yaşla değişiyor. Her şey birbirini izleyen aşamalardan geçmelidir. Hiçbir şey sonsuza kadar olduğu gibi kalmaz. Her şey hareket halinde. Her şey doğa tarafından dönüştürülür ve yeni yollara zorlanır ... Dünya birbirini izleyen aşamalardan geçer, böylece artık yapabildiğini kaldıramaz ve artık daha önce yapamadığını yapabilir.

Romalılar, insanlar da dahil olmak üzere hayvan türlerinin Dünya'nın malzemelerinden kendiliğinden oluştuğuna inanıyordu, çünkü Latince kelime anne"anne", madde ve materyal olarak İngilizce konuşanlara iner. Lucretius'ta Dünya, ilk birkaç satırda şiirin adandığı bir anne olan Venüs'tür. İnsanlığı kendiliğinden nesillerle ortaya çıkardı. Bir tür olarak doğmuş olan insanlar, bireyle kıyaslayarak olgunlaşmalıdır. Kolektif yaşamlarının farklı aşamaları, maddi medeniyet oluşturmak için gelenekler birikimiyle işaretlenir:[14]

İlk silahlar eller, çivi ve dişlerdi. Sonra ağaçlardan koparılmış taşlar ve dallar geldi ve bunlar keşfedilir keşfedilmez ateş ve alevler geldi. Sonra erkekler sert demir ve bakır kullanmayı öğrendi. Bakırla toprağı işlediler. Bakırla çatışan savaş dalgalarını kamçıladılar ... Sonra yavaş yavaş demir kılıç öne çıktı; bronz orak kötü şöhrete düştü; saban adam dünyayı demirle yarmaya başladı, ...

Lucretius, "bugünün erkeklerinden çok daha sert ... Hayatlarını büyük ölçüde dolaşan vahşi hayvanlar tarzında yaşadılar" bir teknoloji öncesi insan tasavvur etti.[15] Bir sonraki aşama kulübelerin, ateşin, giysinin, dilin ve ailenin kullanılmasıydı. Şehir devletleri, krallar ve kaleler onları takip etti. Lucretius, metalin ilk erimesinin yanlışlıkla orman yangınlarında meydana geldiğini varsayar. Bakır kullanımı, taşların ve dalların kullanımını takip etti ve demir kullanımından önce geldi.

Michele Mercati tarafından yapılan erken litik analiz

16. yüzyıla gelindiğinde, gözlemsel olaylara dayalı, doğru ya da yanlış, Avrupa'da büyük miktarlarda dağılmış bulunan siyah nesnelerin gök gürültülü fırtınalar sırasında gökten düştüğü ve bu nedenle şimşek tarafından üretildikleri düşünülen bir gelenek gelişti. Tarafından çok yayınlandılar Konrad Gessner içinde De rerum fossilium, lapidum ve gemmarum maxime figuris ve similitudinibus 1565'te Zürih'te ve daha az ünlü olan pek çok kişi tarafından.[16] "Fırtına" adı verilen ceraunia adı verilmişti.

Ceraunia, yüzyıllar boyunca birçok kişi tarafından toplandı. Michele Mercati, 16. yüzyılın sonlarında Vatikan Botanik Bahçesi Başmüfettişi. Fosil ve taş koleksiyonunu boş zamanlarında incelediği Vatikan'a getirdi ve sonuçlarını 1717'de Roma'da Vatikan tarafından ölümünden sonra yayınlanan bir el yazmasında derledi. Metallotheca. Mercati, kendisine en çok baltalar ve ok başlarına benzeyen ve şimdi ceraunia vulgaris, "halk gök gürültülü taşları" adını verdiği "kama biçimli gök gürültülü taşlar", "kama biçimli gök gürültülü taşlar" ile ilgileniyordu ve bu da onun görüşünü popüler olandan ayırıyordu.[17] Görüşü, ilk derinlemesine olabilecek şeylere dayanıyordu. litik analiz koleksiyonundaki nesnelerin eser olduğunu düşünmesine ve bu eserlerin tarihsel evriminin bir şemayı izlediğini öne sürmesine neden oldu.

Seraunya yüzeylerini inceleyen Mercati, taşların çakmaktaşı olduğunu ve mevcut biçimlerini vurarak elde etmek için başka bir taşla yontulduklarını kaydetti. Alt kısımdaki çıkıntı bir sapın bağlantı noktası olarak belirlendi. Bu nesnelerin ceraunia olmadığı sonucuna vararak, tam olarak ne olduklarını belirlemek için koleksiyonları karşılaştırdı. Vatikan koleksiyonları, Yeni Dünya'dan, sözde seraunyanın şekillerinin aynısını içeriyordu. Kaşiflerin raporları, onların alet ve silah ya da bunların parçaları olduğunu tespit etmişti.[18]

Mercati soruyu kendi kendine sordu, neden biri metal yerine daha üstün bir malzeme olan taştan eserler yapmayı tercih ediyor?[19] Cevabı o zamanlar metalurjinin bilinmiyor olmasıydı. İncil dönemlerinde taşın ilk kullanılan malzeme olduğunu kanıtlamak için İncil pasajlarından alıntı yaptı. Ayrıca, sırasıyla taş (ve ahşap), bronz ve demir kullanımına dayanan bir dizi dönemi tanımlayan Lucretius'un 3 yaş sistemini yeniden canlandırdı. Yayının geç kalması nedeniyle, Mercati'nin fikirleri zaten bağımsız olarak geliştiriliyordu; ancak yazıları bir başka uyarıcı olarak hizmet etti.

Mahudel ve de Jussieu'nun kullanımları

12 Kasım 1734'te, Nicholas Mahudel, doktor, antika ve nümismatçı, kamuya açık bir oturumda bir makale okuyun Académie Royale des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres kronolojik sırayla taş, bronz ve demirin üç "kullanımını" tanımladı. Makaleyi o yıl birkaç kez sunmuştu ancak Kasım revizyonu nihayet kabul edilip 1740'ta Akademi tarafından yayınlanıncaya kadar reddedildi. Les Monumens les plus anciens de l'industrie des hommes ve des Arts, Pierres de Foudres ile yeniden bağlanır.[20] Kavramlarını genişletti Antoine de Jussieu 1723'te kabul edilmiş başlıklı bir bildiri almış olan De l'Origine et des kullanımları de la Pierre de Foudre.[21] Mahudel'de taş için tek bir kullanım değil, bronz ve demir için birer tane daha var.

Tezine, eserin tanımları ve sınıflandırmalarıyla başlar. Pierres de Tonnerre et de Foudre, çağdaş Avrupa çıkarlarının ceraunyası. Seyirciyi, doğal ve insan yapımı nesnelerin genellikle kolayca karıştırılabileceği konusunda uyardıktan sonra, "rakamlar"veya" ayırt edilebilen formlar (daha sessiz yazı tipi farklılıkları oluşturur) "taşların insan yapımı, doğal değil:[22]

Onları alet olarak hizmet ettiren insan eli idi (C'est la main des hommes qui les leur a données pour servir d'instrumens...)

Davalarının "atalarımızın endüstrisi (l'industrie de nos premiers pères"Daha sonra, bronz ve demirin taş olanların kullanımını taklit ettiğini ekleyerek, taşın metallerle değiştirilmesini öneriyor. Mahudel, zaman içinde art arda kullanım fikri için itibar görmemeye dikkat ediyor, ancak şöyle diyor:" Michel Mercatus, bu fikre ilk sahip olan Clement VIII doktoru ".[23] Çağlar için bir terim bulmaz, sadece kullanım zamanlarından bahseder. Onun kullanımı l'industrie 20. yüzyıl "endüstrilerinin" habercisi, ancak modernin belirli alet gelenekleri anlamına geldiği yerlerde, Mahudel yalnızca genel olarak taş ve metal işleme sanatı anlamına geliyordu.

C.J. Thomsen'in üç yaş sistemi

Üç Yaş Sisteminin geliştirilmesinde önemli bir adım, Danimarkalı antikacı Christian Jürgensen Thomsen Danimarka ulusal antika koleksiyonunu ve buluntuların kayıtlarını ve aynı zamanda sistem için sağlam bir ampirik temel oluşturmak için çağdaş kazılardan gelen raporları kullanabildi. Eserlerin türlere göre sınıflandırılabileceğini ve bu türlerin zamanla taş, bronz veya demir alet ve silahların baskınlığıyla ilişkili şekillerde değiştiğini gösterdi. Bu şekilde, Üç-Yaş Sistemini, sezgiye ve genel bilgiye dayalı evrimsel bir şema olmaktan, göreli bir sisteme dönüştürdü. kronoloji arkeolojik kanıtlarla desteklenmektedir. Başlangıçta, Thomsen ve İskandinavya'daki çağdaşları tarafından geliştirilen üç yaşlı sistem, örneğin Sven Nilsson ve J.J.A. Worsaae, geleneksel İncil kronolojisine aşılanmıştır. Ancak, 1830'larda metinsel kronolojilerden bağımsızlık kazandılar ve esas olarak tipoloji ve stratigrafi.[25]

1816'da 27 yaşındaki Thomsen, emekli olan Rasmus Nyerup'un yerine Genel Sekreter olarak atandı. Yaşlılar Opbevaring için Kongelige Komisyonu[26] 1807'de kurulmuş olan ("Eski Eserleri Koruma Kraliyet Komisyonu").[27] Gönderi maaşsızdı; Thomsen'in bağımsız araçları vardı. Piskopos Münter, randevusunda "çok çeşitli başarılara sahip bir amatör" olduğunu söyledi. 1816 ile 1819 arasında komisyonun antika koleksiyonunu yeniden düzenledi. 1819'da koleksiyonları barındırmak için Kopenhag'da eski bir manastırda ilk Kuzey Eski Eserler Müzesi'ni açtı.[28] Daha sonra Ulusal Müze oldu.

Diğer antikacılar gibi Thomsen de şüphesiz ki tarihöncesinin üç çağ modelini Lucretius Dane Vedel Simonsen, Montfaucon ve Mahudel. Koleksiyondaki malzemenin kronolojik olarak sıralanması[29] mevduatlarda hangi tür eserlerin birlikte meydana geldiğini ve hangilerinin olmadığını haritaladı, çünkü bu düzenleme, belirli dönemlere özel eğilimleri ayırt etmesine izin verecekti. Bu yolla, taş aletlerin en erken tortularda bronz veya demir ile bir arada bulunmadığını, ancak daha sonra bronzun demir ile birlikte oluşmadığını keşfetti - böylece mevcut malzemeler, taş, bronz ve demir ile üç dönem tanımlanabilir.

Thomsen'e göre, bulma koşulları flört etmenin anahtarıydı. 1821'de tarih öncesi Schröder'e bir mektup yazdı:[30]

Şimdiye kadar birlikte bulunanlara yeterince dikkat etmediğimizi belirtmekten daha önemli hiçbir şey yoktur.

ve 1822'de:

biz de eski eserlerin çoğu hakkında yeterince bilgi sahibi değiliz; ... sadece geleceğin arkeologları karar verebilir, ancak neyin bir arada bulunduğunu gözlemlemezlerse ve koleksiyonlarımız daha büyük bir mükemmellik derecesine getirilmezse bunu asla yapamayacaklar.

Arkeolojik bağlamda birlikte oluşu ve sistematik ilgiyi vurgulayan bu analiz, Thomsen'in koleksiyondaki materyallerin kronolojik bir çerçevesini oluşturmasına ve yeni bulguları, kökeni hakkında fazla bilgi sahibi olmasa bile, yerleşik kronolojiye göre sınıflandırmasına izin verdi. Bu şekilde, Thomsen'in sistemi evrimsel veya teknolojik bir sistemden çok gerçek bir kronolojik sistemdi.[31] Kronolojisinin tam olarak ne zaman oturduğu net değil, ancak 1825'te müzeye gelen ziyaretçilere yöntemleri konusunda talimat veriliyordu.[32] Aynı yıl J.G.G. Büsching:[33]

Eserleri uygun bağlamlarına yerleştirmek için, kronolojik sıraya dikkat etmenin en önemli olduğunu düşünüyorum ve eski fikrin İskandinavya'ya kadar her zamankinden daha sağlam bir şekilde yerleşmiş olduğuna inanıyorum. endişeli.

1831'de Thomsen, yöntemlerinin faydasından o kadar emindi ki bir broşür dağıttı. "İskandinav Eserleri ve Korunması, arkeologlara her bir yapının bağlamını not etmek için "azami özen göstermelerini" tavsiye ediyor. Broşür anında etkili oldu. Ona bildirilen sonuçlar, Üç Yaş Sisteminin evrenselliğini doğruladı. Thomsen ayrıca 1832 ve 1833'te Oldkyndighed için Nordisk Tidsskrift, "İskandinav Arkeoloji Dergisi."[34] 1836'da Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries, kronolojisini tipoloji ve stratigrafi hakkındaki yorumlarla birlikte ortaya koyduğu "İskandinav Arkeolojisi Rehberi" ne resimli katkısını yayınladığında uluslararası bir üne sahipti.

Thomsen mezar eşyalarının tipolojilerini, mezar türlerini, gömme yöntemlerini, çanak çömlek ve dekoratif motifleri ilk algılayan ve bu türleri kazılarda bulunan katmanlara atayan kişidir. Danimarkalı arkeologlara en iyi kazı yöntemleriyle ilgili yayınlanmış ve kişisel tavsiyesi, yalnızca sistemini ampirik olarak doğrulamakla kalmayıp, Danimarka'yı en az bir nesil boyunca Avrupa arkeolojisinin ön saflarına yerleştiren anında sonuçlar verdi. C.C Rafn,[35] sekreteri Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab ("Kuzey Eski Eserler Kraliyet Cemiyeti"), ana el yazmasını yayınladı[29] içinde Nordisk Oldkyndighed için Ledetraad ("İskandinav Arkeolojisi Rehberi")[36] 1836'da. Sistem o zamandan beri her dönemin daha fazla alt bölümü ile genişletildi ve daha fazla arkeolojik ve antropolojik buluntu ile rafine edildi.

Taş Devri alt bölümleri

Sir John Lubbock'un vahşeti ve medeniyeti

İngiliz arkeolojisi Danimarkalıları yakalamadan önce tam bir nesil olacaktı. Bunu yaptığında, önde gelen kişi, bağımsız araçlara sahip başka bir çok yetenekli adamdı: John Lubbock, 1. Baron Avebury. Lucretius'tan Thomsen'e Üç Yaş Sistemini inceledikten sonra, Lubbock onu geliştirdi ve başka bir düzeye, yani kültürel antropoloji. Thomsen arkeolojik sınıflandırma teknikleriyle ilgilenmişti. Lubbock, vahşilerin ve medeniyetin gelenekleri ile bağıntılar buldu.

1865 tarihli kitabında, Tarih Öncesi ZamanlarLubbock, Avrupa'daki ve muhtemelen daha yakın Asya ve Afrika'daki Taş Devri'ni Paleolitik ve Neolitik:[37]

- "Drift'inki ... Buna 'Paleolitik' Dönem diyebiliriz."

- "Altın dışında herhangi bir metal izine rastlayamadığımız ... sonraki veya cilalanmış Taş Devri ... Buna" Neolitik "Dönem diyebiliriz."

- "Bronzun her türlü silah ve kesici alet için kullanıldığı Bronz Çağı."

- "O metalin bronzun yerini aldığı Demir Çağı."

"Sürüklenme" ile Lubbock, bir nehir tarafından biriken alüvyon nehir kayması anlamına geliyordu. Paleolitik eserlerin yorumlanması için Lubbock, zamanların tarih ve geleneğin erişemeyeceği bir yerde olduğuna işaret ederek, antropologlar tarafından benimsenen bir benzetme önermektedir. Tıpkı paleontologun fosil pachyderm'leri yeniden inşa etmek için modern filleri kullanması gibi, arkeolog da "kıtamızda yaşayan ilk ırkları" anlamak için bugünün "metalik olmayan vahşilerin" geleneklerini kullanmakta haklı.[38] Bu yaklaşıma, Hint ve Pasifik Okyanuslarının ve Batı Yarımküre'nin "modern vahşileri" ni kapsayan üç bölüm ayırıyor, ancak bugün denen şeyde eksik olan bir şey, doğru profesyonelliği henüz emekleme aşamasında olan bir alanı ortaya koyuyor:[39]

Belki de düşünülecek ... Vahşiler için ... en elverişsiz pasajları seçtim. ... Gerçekte durum tam tersi. ... Gerçek durumları benim tasvir etmeye çalıştığımdan çok daha kötü ve daha kötü.

Hodder Westropp'un yakalanması zor Mezolitik'i

Sir John Lubbock'un Paleolitik ("Eski Taş Devri") ve Neolitik ("Yeni Taş Devri") terimlerini kullanması hemen popüler oldu. Bununla birlikte, iki farklı anlamda uygulanmışlardır: jeolojik ve antropolojik. 1867–68'de Ernst Haeckel 20 halka açık konferansta Jena, başlıklı Genel MorfolojiArkeolitik, Paleolitik, Mezolitik ve Caenolitik dönemleri jeolojik tarihteki dönemler olarak 1870 yılında yayınlanacak.[40] Bu terimleri yalnızca Lubbock'tan Paleolitik'i alan, Lubbock'un Neolitik'i yerine Mezolitik ("Orta Taş Devri") ve Caenolitik'i icat eden Hodder Westropp'tan alabilirdi. 1865'ten önce Haeckel'in yazıları da dahil olmak üzere bu terimlerin hiçbiri hiçbir yerde görünmüyor. Haeckel'in kullanımı yenilikçiydi.

Westropp ilk olarak Mezolitik ve Caenolitik'i 1865'te Lubbock'un ilk baskısının yayınlanmasından hemen sonra kullandı. Konuyla ilgili bir makale okudu. Londra Antropoloji Derneği 1865'te, 1866'da Anılar. İddia ettikten sonra:[41]

İnsan, her yaşta ve gelişiminin her aşamasında alet yapan bir hayvandır.

Westropp, "farklı çakmaktaşı, taş, bronz veya demir çağlarını" tanımlamaya devam ediyor; ... Çakmaktaşı Taş Devri'nden asla ayırt edemedi (bunların bir ve aynı olduğunu fark etti), ancak Taş Devri'ni şu şekilde böldü. :[42]

- "Çakmak taşlarının sürüklenmesinin çakmaktaşı aletleri"

- "Çakmaktaşı aletler İrlanda ve Danimarka'da bulundu"

- "Cilalı taş aletler"

Bu üç çağ sırasıyla Paleolitik, Mezolitik ve Kainolitik olarak adlandırıldı. Şunları belirterek bunları nitelendirmeye dikkat etti:[43]

Dolayısıyla onların varlığı her zaman yüksek bir antik çağın kanıtı değil, erken ve barbar bir devletin kanıtıdır; ...

Lubbock'un vahşeti artık Westropp'un barbarlığıydı. Mezolitik dönemin daha kapsamlı bir sergisi kitabını bekliyordu. Tarih Öncesi Aşamalar, 1872'de yayınlanan Sir John Lubbock'a adanmıştır. O sırada Lubbock'un Neolitik Dönemi'ni restore etmiş ve üç aşamaya ve beş aşamaya bölünmüş bir Taş Devri tanımlamıştır.

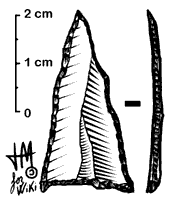

Birinci Aşama, "Çakıl Kaymasının Donanımları", "kabaca şekle sokulmuş" aletleri içerir.[44] Çizimleri Mod 1 ve Mod 2'yi gösteriyor taş aletler, temelde Acheulean el baltası. Bugün Alt Paleolitik Dönem'deler.

İkinci Aşama, "Flint Flakes", "en basit biçimdir" ve çekirdeklerden kesilmiştir.[45] Mod 2 kazıyıcılar ve benzeri aletler için pullar içerdiğinden, Westropp bu tanımda modernden farklıdır. Bununla birlikte, çizimleri Orta ve Üst Paleolitik Dönem 3 ve 4'ü göstermektedir. Kapsamlı litik analizi hiç şüphe bırakmıyor. Bununla birlikte, Westropp'un Mezolitik döneminin bir parçasıdırlar.

"Çakmaktaşı pullarının dikkatlice şekle sokulduğu" "daha gelişmiş bir aşama" olan Üçüncü Aşama, bir çakmak taşı parçasını "yüz parçaya" parçalamaktan, en uygun olanı seçerek ve bir yumrukla çalıştırarak küçük ok uçları üretti.[46] Resimlerde mikrolitler veya Mod 5 araçları aklında olduğunu gösteriyor. Onun Mezolitik Dönemi bu nedenle kısmen modern ile aynıdır.

Dördüncü Aşama, Neolitik Çağın Beşinci Aşamaya geçişi olan bir parçasıdır: tamamen taşlanmış ve cilalanmış uygulamalara giden zemin kenarları olan eksenler. Westropp'un tarımı Bronz Çağı'na kaldırılırken, Neolitik'i pastoraldir. Mezolitik dönem avcılara ayrılmıştır.

Piette Mezolitik'i bulur

Aynı yıl, 1872, efendim John Evans muazzam bir iş üretti, Antik Taş Uygulamaları, Mezolitik'i gerçekte reddettiği, onu görmezden gelmek için bir noktaya işaret ederek, sonraki baskılarda adıyla inkar ettiği. O yazdı:[47]

Sir John Lubbock bunlara sırasıyla Arkeolitik veya Paleolitik ve Neolitik Dönemler demeyi önerdi, bunlar neredeyse genel kabulle karşılanan ve bu çalışma sırasında kendimden yararlanacağım.

Ancak Evans, Lubbock'un tipolojik sınıflandırma olan genel eğilimini takip etmedi. Bunun yerine, Lubbock'un sürüklenme araçları gibi tanımlayıcı terimlerini izleyerek ana kriter olarak bulma sitesi türünü kullanmayı seçti. Lubbock, sürüklenme alanlarının Paleolitik malzeme içerdiğini belirlemişti. Evans onlara mağara sitelerini ekledi. Sürüklenmeye ve mağaraya karşı, yontma ve taşlama aletlerinin genellikle katmanlı olmayan bağlamlarda meydana geldiği yüzey alanlarıydı. Evans, hepsini en yenisine atamaktan başka seçeneği olmadığına karar verdi. Bu nedenle onları Neolitik Çağ'a emanet etti ve bunun için "Yüzey Dönemi" terimini kullandı.

Westropp'u okuyan Sir John, eski Mezolitik aletlerinin yüzey buluntuları olduğunu çok iyi biliyordu. Prestijini Mezolitik kavramını elinden geldiğince bastırmak için kullandı, ancak halk yöntemlerinin tipolojik olmadığını görebiliyordu. Daha küçük dergilerde yayın yapan daha az prestijli bilim adamları Mezolitik'i aramaya devam ettiler. Örneğin, Isaac Taylor içinde Aryanların Kökeni, 1889 Mezolitik dönemden bahseder, ancak kısaca "Paleolitik ve Neolitik Dönemler arasında bir geçiş" oluşturduğunu iddia eder.[48] Yine de, Sir John, eserinin 1897 baskısı kadar geç bir tarihte Mezolitik döneme karşı çıkarak savaşmaya devam etti.

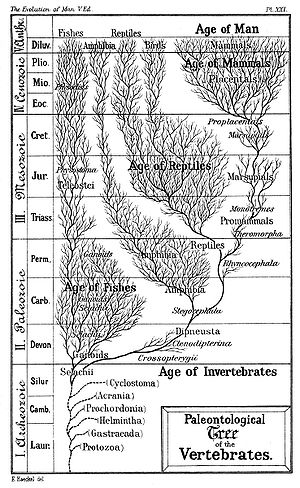

Bu arada Haeckel, -litik terimlerin jeolojik kullanımlarını tamamen terk etmişti. Paleozoik, Mesozoyik ve Senozoik kavramları 19. yüzyılın başlarında ortaya çıkmış ve giderek jeolojik alemin parası haline gelmeye başlamıştı. Adımdan çıktığını fark eden Haeckel, 1876 gibi erken bir tarihte -zoik sisteme geçmeye başladı. Yaratılış Tarihi, -zoik formu parantez içinde -litik formun yanına yerleştirerek.[49]

Eldiven, J.Allen Brown tarafından Sir John'un önüne atıldı. Antropoloji Enstitüsü Günlükte, kayıtta bir "ara" vererek saldırıyı başlatır:[50]

Genel olarak, Avrupa kıtasının Paleolitik Adam ve onun Neolitik halefinin yaşadığı ... dönem arasında bir kopuş olduğu varsayılmıştır ... İnsanlarda böylesine bir kesinti için hiçbir fiziksel neden, yeterli neden atanmamıştır. varoluş ...

O zamanki ana boşluk, İngiliz ve Fransız arkeolojisi arasındaydı, çünkü ikincisi 20 yıl önce boşluğu çoktan keşfetmişti ve zaten üç yanıtı düşünmüş ve tek bir çözüme, modern olana ulaşmıştı. Brown'ın bilmediği ya da bilmiyormuş gibi yaptığı belirsizdir. Evans'ın yayınlandığı 1872'de, Mortillet Boşluğu, Kongrès international d'Anthropologie'ye Brüksel:[51]

Paleolitik ve Neolitik arasında geniş ve derin bir boşluk, büyük bir boşluk vardır.

Görünüşe göre tarih öncesi insan bir yıl taş aletlerle büyük bir oyun avlıyordu ve ertesi yıl evcil hayvanlar ve taş aletlerle tarım yapıyordu. Mortillet bir "zaman sonra bilinmeyen (époque alors inconnue) "boşluğu doldurmak için." Bilinmeyen "arayışı sürüyordu. 16 Nisan 1874'te Mortillet geri çekildi.[52] "Bu boşluk gerçek değil (Cet hiatus n'est pass réel), "dedi Société d'Anthropologie, bunun yalnızca bir bilgi boşluğu olduğunu iddia ederek. Diğer teori, buzul çağı nedeniyle insanın Avrupa'dan çekildiği doğasında bir boşluktu. Bilgi şimdi bulunmalıdır. 1895'te Édouard Piette duyduğunu belirtti Édouard Lartet "ara dönemden kalan kalıntılardan (les vestiges de l'époque intermédiaire) ", henüz keşfedilmemişti, ancak Lartet bu görüşü yayınlamamıştı.[51] Boşluk bir geçiş haline geldi. Ancak Piette şunları söyledi:[53]

Magdalen çağını cilalı taş baltalardan ayıran o bilinmeyen zamanın kalıntılarını keşfettiğim için şanslıydım ... Mas-d'Azil 1887 ve 1888'de bu keşfi yaptığımda.

Tipik alanı kazmıştı. Azilca Kültür, günümüz Mezolitiğinin temeli. Onu Magdalenian ve Neolitik arasında sıkıştırdığını buldu. Aletler Danimarkalılarınki gibiydi mutfak aracı, Westropp'un Mezolitiğinin temeli olan Evans tarafından Yüzey Dönemi olarak adlandırıldı. Onlar Mod 5'ti taş aletler veya mikrolitler. Ne Westropp ne de Mezolitik dönemden bahsetmiyor. Onun için bu bir "süreklilik çözümüydü (Solution de Continuité) "Ona, Neolitik insanın işini büyük ölçüde kolaylaştıran köpek, at, inek, vb .'nin yarı evcilleştirilmesini görevlendirir" (bir beaucoup kolaylaştırıcı la tàche de l'homme néolithiqueBrown, 1892'de Mas-d'Azil'den bahsetmiyor. "Geçiş veya" Mezolitik "formlara atıfta bulunuyor ama ona göre bunlar Evans'ın en eskisi olarak bahsettiği" tüm yüzey boyunca yontulmuş kaba yontulmuş baltalar ". Neolitik.[54] Piette'in yeni bir şey keşfettiğine inandığı yerde Brown, Neolitik olarak kabul edilen bilinen aletleri ortaya çıkarmak istedi.

Stjerna ve Obermaier'in Epipaleolitik ve Protoneolitik'i

Sir John Evans, Mesolitik dönemin ikili görüşüne ve kafa karıştırıcı terimlerin çoğalmasına yol açarak fikrini asla değiştirmedi. Kıtada her şey yerleşmiş görünüyordu: kendi araçlarına sahip ayrı bir Mezolitik dönem vardı ve hem aletler hem de gelenekler Neolitik döneme geçişti. Sonra 1910'da İsveçli arkeolog, Knut Stjerna, Üç-Çağ Sisteminin başka bir sorununu ele aldı: Bir kültür, ağırlıklı olarak bir dönem olarak sınıflandırılmış olsa da, bir başkasıyla aynı veya buna benzer materyaller içerebilir. Onun örneği Galeri mezar İskandinavya dönemi. Tek tip Neolitik değildi, ancak bazı bronz nesneler ve daha da önemlisi onun için üç farklı alt kültür içeriyordu.[55]

İskandinavya'nın kuzey ve doğusunda bulunan bu "medeniyetlerden" (alt kültürler) biri[56] oldukça farklıydı, ancak birkaç galeri mezarı içeriyordu, bunun yerine zıpkın ve cirit başları gibi kemik aletler içeren taş kaplı çukur mezarları kullanıyordu. Bunların "son Paleolitik dönemde ve ayrıca Protoneolitik dönemde de devam ettiklerini" gözlemledi. Burada, kendisine göre Danimarka'ya uygulanacak olan "Protoneolitik" adlı yeni bir terim kullanmıştı. mutfak aracı.[57]

Stjerna ayrıca doğu kültürünün "Paleolitik uygarlığa bağlı olduğunu (medeniyet paléolithique'de se trouve rattachée"Ancak aracı değildi ve aracıları için burada tartışamayız" dedi.nous ne pouvons pas sınavı ici"Bu" bağlı "ve geçişsiz kültüre Epipaleolitik adını vermeyi seçti ve şu şekilde tanımladı:[58]

Epipaleolitik ile, Paleolitik gelenekleri koruyan ren geyiği çağını takip eden ilk günlerdeki dönemi kastediyorum. Bu dönemin İskandinavya'da Maglemose ve Kunda olmak üzere iki aşaması vardır. (Par époque épipaléolithique j'entends la période qui, pandantif prömiyerleri geçici olarak sessiz, Renne, les coutumes paléolithiques'i korur. Cette période présente deux étapes en Scandinavie, celle de Maglemose ve Kunda.)

Herhangi bir Mezolitik Çağ'dan söz edilmiyor, ancak anlattığı malzeme daha önce Mezolitik ile bağlantılıydı. Stjerna'nın Protoneolitik ve Epipaleolitik dönemini Mezolitik'in yerini alacak şekilde tasarlayıp amaçlamadığı açık değil, ancak Hugo Obermaier İspanya'da uzun yıllar ders veren ve çalışan bir Alman arkeolog, kavramların çoğu kez hatalı bir şekilde atfedildiği, bunları tüm Mezolitik kavramına bir saldırı düzenlemek için kullandı. Görüşlerini sundu El Hombre fósil, 1916, 1924'te İngilizce'ye çevrildi. Epipaleolitik ve Protoneolitik'i bir "geçiş" ve "geçici" olarak gördüğünde, bunların herhangi bir "dönüşüm" olmadığını doğruladı:[59]

Ancak bence bu terim, bu evrelerin doğal bir evrimsel gelişim - Paleolitik'ten Neolitik'e ilerici bir dönüşüm - sunması durumunda olduğu gibi haklı değildir. Gerçekte, son aşama Capsian, Tardenoisiyen, Azilca ve kuzey Maglemose endüstriler Paleolitik dönemin ölümünden sonra gelen torunlarıdır ...

Stjerna ve Obermaier'in fikirleri, daha sonraki arkeologların bulduğu ve kafa karıştırıcı bulduğu terminolojiye belirli bir belirsizlik getirdi. Epipaleolitik ve Protoneolitik, Mezolitik çağda olduğu gibi aşağı yukarı aynı kültürleri kapsar. 1916'dan sonra Taş Devri üzerine yapılan yayınlar, bu belirsizliğin bir tür açıklamasını içeriyor ve farklı görüşlere yer bırakıyor. Strictly speaking the Epipaleolithic is the earlier part of the Mesolithic. Some identify it with the Mesolithic. To others it is an Upper Paleolithic transition to the Mesolithic. The exact use in any context depends on the archaeological tradition or the judgement of individual archaeologists. The issue continues.

Lower, middle and upper from Haeckel to Sollas

Posta-Darwinci approach to the naming of periods in earth history focused at first on the lapse of time: early (Palaeo-), middle (Meso-) and late (Ceno-). This conceptualization automatically imposes a three-age subdivision to any period, which is predominant in modern archaeology: Early, Middle and Late Bronze Age; Early, Middle and Late Minoan, etc. The criterion is whether the objects in question look simple or are elaborative. If a horizon contains objects that are post-late and simpler-than-late they are sub-, as in Submycenaean.

Haeckel's presentations are from a different point of view. Onun History of Creation of 1870 presents the ages as "Strata of the Earth's Crust," in which he prefers "upper", "mid-" and "lower" based on the order in which one encounters the layers. His analysis features an Upper and Lower Pliocene as well as an Upper and Lower Diluvial (his term for the Pleistocene).[49] Haeckel, however, was relying heavily on Lyell. In the 1833 edition of Jeolojinin İlkeleri (the first) Lyell devised the terms Eosen, Miyosen ve Pliyosen to mean periods of which the "strata" contained some (Eo-, "early"), lesser (Mio-) and greater (Plio-) numbers of "living Mollusca represented among fossil assemblages of western Europe."[60] The Eocene was given Lower, Middle, Upper; the Miocene a Lower and Upper; and the Pliocene an Older and Newer, which scheme would indicate an equivalence between Lower and Older, and Upper and Newer.

In a French version, Nouveaux Éléments de Géologie, in 1839 Lyell called the Older Pliocene the Pliocene and the Newer Pliocene the Pleistocene (Pleist-, "most"). Daha sonra Antiquity of Man in 1863 he reverted to his previous scheme, adding "Post-Tertiary" and "Post-Pliocene." In 1873 the Fourth Edition of Antiquity of Man restores Pleistocene and identifies it with Post-Pliocene. As this work was posthumous, no more was heard from Lyell. Living or deceased, his work was immensely popular among scientists and laymen alike. "Pleistocene" caught on immediately; it is entirely possible that he restored it by popular demand. 1880'de Dawkins yayınlanan The Three Pleistocene Strata containing a new manifesto for British archaeology:[61]

The continuity between geology, prehistoric archaeology and history is so direct that it is impossible to picture early man in this country without using the results of all these three sciences.

He intends to use archaeology and geology to "draw aside the veil" covering the situations of the peoples mentioned in proto-historic documents, such as Sezar 's Yorumlar ve Agricola nın-nin Tacitus. Adopting Lyell's scheme of the Tertiary, he divides Pleistocene into Early, Mid- and Late.[62] Only the Palaeolithic falls into the Pleistocene; the Neolithic is in the "Prehistoric Period" subsequent.[63] Dawkins defines what was to become the Upper, Middle and Lower Paleolithic, except that he calls them the "Upper Cave-Earth and Breccia,"[64] the "Middle Cave-Earth,"[65] and the "Lower Red Sand,"[66] with reference to the names of the layers. The next year, 1881, Geikie solidified the terminology into Upper and Lower Palaeolithic:[67]

In Kent's Cave the implements obtained from the lower stages were of a much ruder description than the various objects detected in the upper cave-earth ... And a very long time must have elapsed between the formation of the lower and upper Palaeolithic beds in that cave.

The Middle Paleolithic in the modern sense made its appearance in 1911 in the 1st edition of William Johnson Sollas ' Ancient Hunters.[68] It had been used in varying senses before then. Sollas associates the period with the Mousterian technology and the relevant modern people with the Tazmanyalılar. In the 2nd edition of 1915 he has changed his mind for reasons that are not clear. The Mousterian has been moved to the Lower Paleolithic and the people changed to the Avustralya yerlileri; furthermore, the association has been made with Neanderthals and the Levalloisiyen katma. Sollas says wistfully that they are in "the very middle of the Palaeolithic epoch." Whatever his reasons, the public would have none of it. From 1911 on, Mousterian was Middle Paleolithic, except for holdouts. Alfred L. Kroeber 1920'de Three essays on the antiquity and races of man, reverting to Lower Paleolithic, explains that he is following Louis Laurent Gabriel de Mortillet. The English-speaking public remained with Middle Paleolithic.

Early and late from Worsaae through the three-stage African system

Thomsen had formalized the Three-age System by the time of its publication in 1836. The next step forward was the formalization of the Palaeolithic and Neolithic by Sir John Lubbock in 1865. Between these two times Denmark held the lead in archaeology, especially because of the work of Thomsen's at first junior associate and then successor, Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae, rising in the last year of his life to Kultus Minister of Denmark. Lubbock offers full tribute and credit to him in Prehistoric Times.

Worsaae in 1862 in Om Tvedelingen af Steenalderen, previewed in English even before its publication by Centilmen Dergisi, concerned about changes in typology during each period, proposed a bipartite division of each age:[69]

Both for Bronze and Stone it was now evident that a few hundred years would not suffice. In fact, good grounds existed for dividing each of these periods into two, if not more.

He called them earlier or later. The three ages became six periods. The British seized on the concept immediately. Worsaae's earlier and later became Lubbock's palaeo- and neo- in 1865, but alternatively English speakers used Earlier and Later Stone Age, as did Lyell's 1883 edition of Jeolojinin İlkeleri, with older and younger as synonyms. As there is no room for a middle between the comparative adjectives, they were later modified to early and late. The scheme created a problem for further bipartite subdivisions, which would have resulted in such terms as early early Stone Age, but that terminology was avoided by adoption of Geikie's upper and lower Paleolithic.

Amongst African archaeologists[DSÖ? ], the terms Old Stone Age, Orta Taş Devri ve Geç Taş Devri tercih edilmektedir.

Wallace's grand revolution recycled

When Sir John Lubbock was doing the preliminary work for his 1865 magnum opus, Charles Darwin ve Alfred Russel Wallace were jointly publishing their first papers On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection. Darwins's Türlerin Kökeni came out in 1859, but he did not elucidate the Evrim Teorisi as it applies to man until the Descent of Man in 1871. Meanwhile, Wallace read a paper in 1864 to the Anthropological Society of London that was a major influence on Sir John, publishing in the very next year.[70] He quoted Wallace:[71]

From the moment when the first skin was used as a covering, when the first rude spear was formed to assist in the chase, the first seed sown or shoot planted, a grand revolution was effected in nature, a revolution which in all the previous ages of the world's history had had no parallel, for a being had arisen who was no longer necessarily subject to change with the changing universe,—a being who was in some degree superior to nature, inasmuch as he knew how to control and regulate her action, and could keep himself in harmony with her, not by a change in body, but by an advance in mind.

Wallace distinguishing between mind and body was asserting that Doğal seçilim shaped the form of man only until the appearance of mind; after then, it played no part. Mind formed modern man, meaning that result of mind, culture. Its appearance overthrew the laws of nature. Wallace used the term "grand revolution." Although Lubbock believed that Wallace had gone too far in that direction he did adopt a theory of evolution combined with the revolution of culture. Neither Wallace not Lubbock offered any explanation of how the revolution came about, or felt that they had to offer one. Revolution is an acceptance that in the continuous evolution of objects and events sharp and inexplicable disconformities do occur, as in geology. And so it is not surprising that in the 1874 Stockholm buluşması International Congress of Anthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology, in response to Ernst Hamy's denial of any "break" between Paleolithic and Neolithic based on material from dolmenler near Paris "showing a continuity between the paleolithic and neolithic folks," Edouard Desor, geologist and archaeologist, replied:[72] "that the introduction of domesticated animals was a complete revolution and enables us to separate the two epochs completely."

A revolution as defined by Wallace and adopted by Lubbock is a change of regime, or rules. If man was the new rule-setter through culture then the initiation of each of Lubbock's four periods might be regarded as a change of rules and therefore as a distinct revolution, and so Chambers Dergisi, a reference work, in 1879 portrayed each of them as:[73]

...an advance in knowledge and civilization which amounted to a revolution in the then existing manners and customs of the world.

Because of the controversy over Westropp's Mesolithic and Mortillet's Gap beginning in 1872 archaeological attention focused mainly on the revolution at the Palaeolithic—Neolithic boundary as an explanation of the gap. For a few decades the Neolithic Period, as it was called, was described as a kind of revolution. In the 1890s, a standard term, the Neolithic Revolution, began to appear in encyclopedias such as Pears. 1925'te Cambridge Antik Tarih bildirildi:[74]

There are quite a large number of archaeologists who justifiably consider the period of the Late Stone Age to be a Neolithic revolution and an economic revolution at the same time. For that is the period when primitive agriculture developed and cattle breeding began.

Vere Gordon Childe's revolution for the masses

In 1936 a champion came forward who would advance the Neolithic Revolution into the mainstream view: Vere Gordon Childe. After giving the Neolithic Revolution scant mention in his first notable work, the 1928 edition of New Light on the Most Ancient East, Childe made a major presentation in the first edition of Man Makes Himself in 1936 developing Wallace's and Lubbock's theme of the human revolution against the supremacy of nature and supplying detail on two revolutions, the Paleolithic—Neolithic and the Neolithic-Bronze Age, which he called the Second or Urban revolution.

Lubbock had been as much of an etnolog bir arkeolog olarak. Kurucuları kültürel antropoloji, gibi Tylor ve Morgan, were to follow his lead on that. Lubbock created such concepts as savages and barbarians based on the customs of then modern tribesmen and made the presumption that the terms can be applied without serious inaccuracy to the men of the Paleolithic and the Neolithic. Childe broke with this view:[75]

The assumption that any savage tribe today is primitive, in the sense that its culture faithfully reflects that of much more ancient men is gratuitous.

Childe concentrated on the inferences to be made from the artifacts:[76]

But when the tools ... are considered ... in their totality, they may reveal much more. They disclose not only the level of technical skill ... but also their economy .... The archaeologists's ages correspond roughly to economic stages. Each new "age" is ushered in by an economic revolution ....

The archaeological periods were indications of economic ones:[77]

Archaeologists can define a period when it was apparently the sole economy, the sole organization of production ruling anywhere on the earth's surface.

These periods could be used to supplement historical ones where history was not available. He reaffirmed Lubbock's view that the Paleolithic was an age of food gathering and the Neolithic an age of food production. He took a stand on the question of the Mesolithic identifying it with the Epipaleolithic. The Mesolithic was to him "a mere continuance of the Old Stone Age mode of life" between the end of the Pleistosen and the start of the Neolithic.[78] Lubbock's terms "savagery" and "barbarism" do not much appear in Man Makes Himself ama devamı What Happened in History (1942), reuses them (attributing them to Morgan, who got them from Lubbock) with an economic significance: savagery for food-gathering and barbarism for Neolithic food production. Civilization begins with the urban revolution of the Bronze Age.[79]

The Pre-pottery Neolithic of Garstang and Kenyon at Jericho

Even as Childe was developing this revolution theme the ground was sinking under him. Lubbock did not find any pottery associated with the Paleolithic, asserting of its to him last period, the Reindeer, "no fragments of metal or pottery have yet been found."[80] He did not generalize but others did not hesitate to do so. The next year, 1866, Dawkins proclaimed of Neolithic people that "these invented the use of pottery...."[81] From then until the 1930s pottery was considered a olmazsa olmaz of the Neolithic. The term Pre-Pottery Age came into use in the late 19th century but it meant Paleolithic.

Bu arada Filistin Arama Fonu founded in 1865 completing its survey of excavatable sites in Palestine in 1880 began excavating in 1890 at the site of ancient Lakiş yakın Kudüs, the first of a series planned under the licensing system of the Osmanlı imparatorluğu. Under their auspices in 1908 Ernst Sellin ve Carl Watzinger began excavation at Jericho (Tell es-Sultan ) previously excavated for the first time by Sir Charles Warren in 1868. They discovered a Neolithic and Bronze Age city there. Subsequent excavations in the region by them and others turned up other walled cities that appear to have preceded the Bronze Age urbanization.

All excavation ceased for birinci Dünya Savaşı. When it was over the Ottoman Empire was no longer a factor there. In 1919 the new British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem assumed archaeological operations in Palestine. John Garstang finally resumed excavation at Jericho 1930-1936. The renewed dig uncovered another 3000 years of prehistory that was in the Neolithic but did not make use of pottery. O buna Pre-pottery Neolithic, as opposed to the Pottery Neolithic, subsequently often called the Aceramic or Pre-ceramic and Ceramic Neolithic.

Kathleen Kenyon was a young photographer then with a natural talent for archaeology. Solving a number of dating problems she soon advanced to the forefront of British archaeology through skill and judgement. İçinde Dünya Savaşı II she served as a commander in the Kızıl Haç. In 1952–58 she took over operations at Jericho as the Director of the British School, verifying and expanding Garstang's work and conclusions.[82] There were two Pre-pottery Neolithic periods, she concluded, A and B. Moreover, the PPN had been discovered at most of the major Neolithic sites in the near East and Greece. By this time her personal stature in archaeology was at least equal to that of V. Gordon Childe. While the three-age system was being attributed to Childe in popular fame, Kenyon became gratuitously the discoverer of the PPN. More significantly the question of revolution or evolution of the Neolithic was increasingly being brought before the professional archaeologists.

Bronze Age subdivisions

Danish archaeology took the lead in defining the Bronze Age, with little of the controversy surrounding the Stone Age. British archaeologists patterned their own excavations after those of the Danish, which they followed avidly in the media. References to the Bronze Age in British excavation reports began in the 1820s contemporaneously with the new system being promulgated by C.J. Thomsen. Mention of the Early and Late Bronze Age began in the 1860s following the bipartite definitions of Worsaae.

The tripartite system of Sir John Evans

In 1874 at the Stockholm buluşması International Congress of Anthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology, a suggestion was made by A. Bertrand that no distinct age of bronze had existed, that the bronze artifacts discovered were really part of the Iron Age. Hans Hildebrand in refutation pointed to two Bronze Ages and a transitional period in Scandinavia. John Evans denied any defect of continuity between the two and asserted there were three Bronze Ages, "the early, middle and late Bronze Age."[83]

His view for the Stone Age, following Lubbock, was quite different, denying, in The Ancient Stone Implements, any concept of a Middle Stone Age. In his 1881 parallel work, The Ancient Bronze Implements, he affirmed and further defined the three periods, strangely enough recusing himself from his previous terminology, Early, Middle and Late Bronze Age (the current forms) in favor of "an earlier and later stage"[84] and "middle".[85] He uses Bronze Age, Bronze Period, Bronze-using Period and Bronze Civilization interchangeably. Apparently Evans was sensitive of what had gone before, retaining the terminology of the bipartite system while proposing a tripartite one. After stating a catalogue of types of bronze implements he defines his system:[86]

The Bronze Age of Britain may, therefore, be regarded as an aggregate of three stages: the first, that characterized by the flat or slightly flanged celts, and the knife-daggers ... the second, that characterized by the more heavy dagger-blades and the flanged celts and tanged spear-heads or daggers, ... and the third, by palstaves and socketed celts and the many forms of tools and weapons, ... It is in this third stage that the bronze sword and the true socketed spear-head first make their advent.

From Evans' gratuitous Copper Age to the mythical chalcolithic

In chapter 1 of his work, Evans proposes for the first time a transitional Bakır Çağı arasında Neolitik ve Bronz Çağı. He adduces evidence from far-flung places such as China and the Americas to show that the smelting of copper universally preceded alloying with teneke to make bronze. He does not know how to classify this fourth age. On the one hand he distinguishes it from the Bronze Age. On the other hand, he includes it:[87]

In thus speaking of a bronze-using period I by no means wish to exclude the possible use of copper unalloyed with tin.

Evans goes into considerable detail tracing references to the metals in classical literature: Latin aer, aeris ve Yunanca chalkós first for "copper" and then for "bronze." He does not mention the adjective of aes, hangisi aēneus, nor is he interested in formulating New Latin words for the Copper Age, which is good enough for him and many English authors from then on. He offers literary proof that bronze had been in use before iron and copper before bronze.[88]

In 1884 the center of archaeological interest shifted to Italy with the excavation of Remedello and the discovery of the Remedello culture by Gaetano Chierici. According to his 1886 biographers, Luigi Pigorini and Pellegrino Strobel, Chierici devised the term Età Eneo-litica to describe the archaeological context of his findings, which he believed were the remains of Pelasgians, or people that preceded Greek and Latin speakers in the Mediterranean. The age (Età) was:[89]

A period of transition from the age of stone to that of bronze (periodo di transizione dall'età della pietra a quella del bronzo)

Whether intentional or not, the definition was the same as Evans', except that Chierici was adding a term to New Latin. He describes the transition by stating the beginning (litica, or Stone Age) and the ending (eneo-, or Bronze Age); in English, "the stone-to-bronze period." Shortly after, "Eneolithic" or "Aeneolithic" began turning up in scholarly English as a synonym for "Copper Age." Sir John's own son, Arthur Evans, beginning to come into his own as an archaeologist and already studying Cretan civilization, refers in 1895 to some clay figures of "aeneolithic date" (quotes his).

End of the Iron Age

The three-age system is a way of dividing prehistory, and the Iron Age is therefore considered to end in a particular culture with either the start of its ön tarih, when it begins to be written about by outsiders, or when its own tarih yazımı begins. Although iron is still the major hard material in use in modern civilization, and steel is a vital and indispensable modern industry, as far as archaeologists are concerned the Iron Age has therefore now ended for all cultures in the world.

The date when it is taken to end varies greatly between cultures, and in many parts of the world there was no Iron Age at all, for example in Kolomb Öncesi Amerika ve prehistory of Australia. For these and other regions the three-age system is little used. By a convention among archaeologists, in the Antik Yakın Doğu the Iron Age is taken to end with the start of the Ahameniş İmparatorluğu in the 6th century BC, as the history of that is told by the Greek historian Herodot. This remains the case despite a good deal of earlier local written material having become known since the convention was established. In Western Europe the Iron Age is ended by Roman conquest. In South Asia the start of the Maurya İmparatorluğu about 320 BC is usually taken as the end point; although we have a considerable quantity of earlier written texts from India, they give us relatively little in the way of a conventional record of political history. For Egypt, China and Greece "Iron Age" is not a very useful concept, and relatively little used as a period term. In the first two prehistory has ended, and periodization by historical ruling dynasties has already begun, in the Bronze Age, which these cultures do have. In Greece the Iron Age begins during the Yunan Karanlık Çağı, and coincides with the cessation of a historical record for some centuries. İçin İskandinavya and other parts of northern Europe that the Romans did not reach, the Iron Age continues until the start of the Viking Çağı in about 800 AD.

Flört

The question of the dates of the objects and events discovered through archaeology is the prime concern of any system of thought that seeks to summarize history through the formulation of yaşlar veya çağlar. An age is defined through comparison of contemporaneous events. Increasingly,[kaynak belirtilmeli ] the terminology of archaeology is parallel to that of historical method. An event is "undocumented" until it turns up in the archaeological record. Fossils and artifacts are "documents" of the epochs hypothesized. The correction of dating errors is therefore a major concern.

In the case where parallel epochs defined in history were available, elaborate efforts were made to align European and Yakın Doğu sequences with the datable chronology of Antik Mısır and other known civilizations. The resulting grand sequence was also spot checked by evidence of calculateable solar or other astronomical events.[kaynak belirtilmeli ] These methods are only available for the relatively short term of recorded history. Most prehistory does not fall into that category.

Physical science provides at least two general groups of dating methods, stated below. Data collected by these methods is intended to provide an absolute chronology to the framework of periods defined by relative chronology.

Grand systems of layering

The initial comparisons of artifacts defined periods that were local to a site, group of sites or region.Advances made in the fields of seriation, tipoloji, tabakalaşma and the associative dating of artifacts and features permitted even greater refinement of the system. The ultimate development is the reconstruction of a global catalogue of layers (or as close to it as possible) with different sections attested in different regions. Ideally once the layer of the artifact or event is known a quick lookup of the layer in the grand system will provide a ready date. This is considered the most reliable method. It is used for calibration of the less reliable chemical methods.

Measurement of chemical change

Any material sample contains elements and compounds that are subject to decay into other elements and compounds. In cases where the rate of decay is predictable and the proportions of initial and end products can be known exactly, consistent dates of the artifact can be calculated. Due to the problem of sample contamination and variability of the natural proportions of the materials in the media, sample analysis in the case where verification can be checked by grand layering systems has often been found to be widely inaccurate. Chemical dates therefore are only considered reliable used in conjunction with other methods. They are collected in groups of data points that form a pattern when graphed. Isolated dates are not considered reliable.

Other -liths and -lithics

Dönem Megalitik does not refer to a period of time, but merely describes the use of large stones by ancient peoples from any period. Bir eolith is a stone that might have been formed by natural process but occurs in contexts that suggest modification by early humans or other primates for percussion.

Three-age system resumptive table

| Yaş | Periyot | Araçlar | Ekonomi | Dwelling sites | Toplum | Din |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taş Devri (3.4 mya – 2000 bce) | Paleolitik | Handmade tools and objects found in nature – cudgel, kulüp, sharpened stone, helikopter, handaxe, kazıyıcı, mızrak, zıpkın, iğne, scratch awl. Genel olarak taş aletler of Modes I—IV. | Avcılık ve toplama | Mobile lifestyle – caves, huts, tusk/bone or skin hovels, mostly by rivers and lakes [açıklama gerekli How can a dwelling be made of teeth?][kaynak belirtilmeli ] | Bir grup of edible-plant gatherers and hunters (25–100 people) | Evidence for belief in the afterlife first appears in the Üst Paleolitik, marked by the appearance of burial rituals and atalara tapınma. Shamans, priests and barınak hizmetkarlar görünmek tarih öncesi. |

| Mezolitik (other name epipalaeolithic ) | Mode V tools employed in composite devices – zıpkın, eğilmek ve ok. Other devices such as fishing baskets, boats | Intensive hunting and gathering, porting of wild animals and seeds of wild plants for domestic use and planting | Temporary villages at opportune locations for economic activities | Kabileler ve gruplar | ||

| Neolitik | Polished stone tools, devices useful in subsistence farming and defense – keski, çapa, pulluk, boyunduruk, reaping-hook, grain pourer, tezgah, çanak çömlek (çanak çömlek ) ve silahlar | Neolitik Devrim - evcilleştirme of plants and animals used in agriculture and herding, supplementary toplama, Avcılık ve Balıkçılık. Savaş. | Permanent settlements varying in size from villages to walled cities, public works. | Tribes and formation of şeflikler in some Neolithic societies the end of the period | Şirk, sometimes presided over by the ana tanrıça, şamanizm | |

| Bronz Çağı (3300 – 300 bce) | Bakır Çağı (Kalkolitik ) | Copper tools, çömlekçinin tekerleği | Civilization, including zanaat, trade | Urban centers surrounded by politically attached communities | Kent-eyaletler * | Ethnic gods, state religion |

| Bronz Çağı | Bronze tools | |||||

| Demir Çağı (1200 – 550 bce) | Iron tools | Includes trade and much specialization; often taxes | Includes towns or even large cities, connected by roads | Large tribes, kingdoms, empires | One or more religions sanctioned by the state | |

* Formation of states starts during the Early Bronze Age in Egypt and Mesopotamia and during the Late Bronze Age first empires are founded.

Eleştiri

The Three-age System has been criticized since at least the 19th century. Every phase of its development has been contested. Some of the arguments that have been presented against it follow.

Unsound epochalism

In some cases criticism resulted in other, parallel three-age systems, such as the concepts expressed by Lewis Henry Morgan içinde Antik toplum, dayalı ethnology. These disagreed with the metallic basis of epochization. The critic generally substituted his own definitions of epochs. Vere Gordon Childe said of the early cultural anthropologists:[90]

Last century Herbert Spencer, Lewis H. Morgan ve Tylor propounded divergent schemes ... they arranged these in a logical order .... They assumed that the logical order was a temporal one.... The competing systems of Morgan and Tylor remained equally unverified—and incompatible—theories.

More recently, many archaeologists have questioned the validity of dividing time into epochs at all. For example, one recent critic, Graham Connah, describes the three-age system as "epochalism" and asserts:[91]

So many archaeological writers have used this model for so long that for many readers it has taken on a reality of its own. In spite of the theoretical agonizing of the last half-century, epochalism is still alive and well ... Even in parts of the world where the model is still in common use, it needs to be accepted that, for example, there never was actually such a thing as 'the Bronze Age.'

Simplisticism

Some view the three-age system as over-simple; that is, it neglects vital detail and forces complex circumstances into a mold they do not fit. Rowlands argues that the division of human societies into epochs based on the presumption of a single set of related changes is not realistic:[92]

But as a more rigorous sociological approach has begun to show that changes at the economic, political and ideological levels are not 'all of apiece' we have come to realise that time may be segmented in as many ways as convenient to the researcher concerned.

The three-age system is a relative chronology. The explosion of archaeological data acquired in the 20th century was intended to elucidate the relative chronology in detail. One consequence was the collection of absolute dates. Connah argues:[91]

Gibi radyokarbon and other forms of absolute dating contributed more detailed and more reliable chronologies, the epochal model ceased to be necessary.

Peter Bogucki of Princeton University summarizes the perspective taken by many modern archaeologists:[93]

Although modern archaeologists realize that this tripartite division of prehistoric society is far too simple to reflect the complexity of change and continuity, terms like 'Bronze Age' are still used as a very general way of focusing attention on particular times and places and thus facilitating archaeological discussion.

Avrupa merkezcilik

Another common criticism attacks the broader application of the three-age system as a cross-cultural model for social change. The model was originally designed to explain data from Europe and West Asia, but archaeologists have also attempted to use it to explain social and technological developments in other parts of the world such as the Americas, Australasia, and Africa.[94] Many archaeologists working in these regions have criticized this application as eurocentric. Graham Connah writes that:[91]

... attempts by Eurocentric archaeologists to apply the model to African archaeology have produced little more than confusion, whereas in the Americas or Australasia it has been irrelevant, ...

Alice B. Kehoe further explains this position as it relates to American archaeology:[94]

... Professor Wilson's presentation of prehistoric archaeology[95] was a European product carried across the Atlantic to promote an American science compatible with its European model.

Kehoe goes on to complain of Wilson that "he accepted and reprised the idea that the European course of development was paradigmatic for humankind."[96] This criticism argues that the different societies of the world underwent social and technological developments in different ways. A sequence of events that describes the developments of one civilization may not necessarily apply to another, in this view. Instead social and technological developments must be described within the context of the society being studied.

Ayrıca bakınız

Referanslar

- ^ Lele, Ajey (2018). Disruptive Technologies for the Militaries and Security. Akıllı Yenilik, Sistemler ve Teknolojiler. 132. Singapur: Springer. s. xvi. ISBN 9789811333842. Alındı 30 Eylül 2019.

Some [researchers] have related the progression of mankind directly (or indirectly) based on technology-connected parameters like the three-age system (labelling of history into time periods divisible by three), i.e. Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age. At present, the era of Industrial Age, Information Age and Digital Age is in vogue.

- ^ "Craniology and the Adoption of the Three-Age System in Britain". Cambridge Press. Alındı 27 Aralık 2016.

- ^ Julian Richards (24 January 2005). "BBC - History - Notepads to Laptops: Archaeology Grows Up". BBC. Alındı 27 Aralık 2016.

- ^ "Three-age System - oi". Oxford Endeksi. Alındı 27 Aralık 2016.

- ^ "John Lubbock's "Pre-Historic Times" is Published (1865)". Bilgi Tarihi. Alındı 27 Aralık 2016.

- ^ "About the three Age System of Prehistory Archaeology". Act for Libraries. Alındı 27 Aralık 2016.

- ^ Barnes, s. 27–28.

- ^ Lines 109-201.

- ^ Lines 140-155, translator Richmond Lattimore.

- ^ "Ages of Man According to Hesiod | Thomas Armstrong, Ph.D." www.institute4learning.com. Alındı 29 Mayıs 2020.

- ^ Lines 161-169.

- ^ Beye, Charles Rowan (January 1963). "Lucretius and Progress". Klasik Dergi. 58 (4): 160–169.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- ^ De Rerum Natura, Book V, about Line 800 ff. The translator is Ronald Latham.

- ^ De Rerum Natura, Book V, around Line 1200 ff.

- ^ De Rerum Natura, Book V around Line 940 ff.

- ^ Goodrum 2008, s. 483

- ^ Goodrum 2008, s. 494

- ^ Goodrum 2008, s. 495

- ^ Goodrum 2008, s. 496.

- ^ Hamy 1906, pp. 249–251

- ^ Hamy 1906, s. 246

- ^ Hamy 1906, s. 252

- ^ Hamy 1906, s. 259: "c'est a Michel Mercatus, Médecin de Clément VIII, que la première idée est duë..."

- ^ Rowley-Conwy 2007, s. 40

- ^ Rowley-Conwy 2007, s. 22

- ^ Rowley-Conwy 2007, s. 36

- ^ Rowley-Conwy 2007, Front Matter, Abbreviations

- ^ Malina & Vašíček 1990, s. 37

- ^ a b Rowley-Conwy 2007, s. 38

- ^ Gräslund 1987, s. 23

- ^ Gräslund 1987, pp. 22, 28

- ^ Gräslund 1987, s. 18–19

- ^ Rowley-Conwy 2007, pp. 298–301

- ^ Gräslund 1987, s. 24

- ^ Thomsen, Christian Jürgensen (1836). "Kortfattet udsigt over midesmaeker og oldsager fra Nordens oldtid". In Rafn, C.C (ed.). Ledetraad til Nordisk Oldkyndighed (Danca). Copenhagen: Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı).

- ^ This was not the museum guidebook, which was written by Julius Sorterup, an assistant of Thomsen, and published in 1846. Note that translations of Danish organizations and publications tend to vary somewhat.

- ^ Lubbock 1865, s. 2–3

- ^ Lubbock 1865, pp. 336–337

- ^ Lubbock 1865, s. 472

- ^ "Yorumlar". The Medical Times and Gazette: A Journal of Medical Science, Literature, Criticism and News. London: John Churchill and Sons. II. 6 August 1870.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- ^ Westropp 1866, s. 288

- ^ Westropp 1866, s. 291

- ^ Westropp 1866, s. 290

- ^ Westropp 1872, s. 41

- ^ Westropp 1872, s. 45

- ^ Westropp 1872, s. 53

- ^ Evans 1872, s. 12

- ^ Taylor, Isaac (1889). The Origin of the Aryans. An Account of the Prehistoric Ethnology and Civilisation of Europe. New York: C. Scribner's sones. s. 60.

- ^ a b Haeckel, Ernst Heinrich Philipp August; Lankester, Edwin Ray (1876). The history of creation, or, The development of the earth and its inhabitants by the action of natural causes : a popular exposition of the doctrine of evolution in general, and of that of Darwin, Goethe, and Lamarck in particular. New York: D. Appleton. s.15.

- ^ Brown 1893, s. 66

- ^ a b Piette 1895, s. 236: "Entre le paléolithique et le neolithique, il y a une large et profonde lacune, un grand hiatus; ..."

- ^ Piette 1895, s. 237

- ^ Piette 1895, s. 239: "J'ai eu la bonne fortune découvrir les restes de cette époque ignorée qui sépara l'àge magdalénien de celui des haches en pierre polie ... ce fut, au Mas-d'Azil, en 1887 et en 1888 que je fis cette découverte."

- ^ Brown 1893, s. 74–75.

- ^ Stjerna 1910, s. 2

- ^ Stjerna 1910, s. 10

- ^ Stjerna 1910, s. 12: "... a persisté pendant la période paléolithique récente et même pendant la période protonéolithique."

- ^ Stjerna 1910, s. 12

- ^ Obermaier, Hugo (1924). Fossil man in Spain. New Haven: Yale Üniversitesi Yayınları. s.322.

- ^ Farrand, W.R. (1990). "Origins of Quaternary-Pleistocene-Holocene Stratigraphic Terminology". In Laporte, Léo F. (ed.). Establishment of a Geologic Framework for Paleoanthropology. Special Paper 242. Boulder: Geological Society of America. sayfa 16–18.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- ^ Dawkins 1880, s. 3

- ^ Dawkins 1880, s. 124

- ^ Dawkins 1880, s. 247

- ^ Dawkins 1880, s. 183

- ^ Dawkins 1880, s. 181

- ^ Dawkins 1880, s. 178

- ^ Geikie, James (1881). Prehistoric Europe: A Geological Sketch. Londra: Edward Stanford..

- ^ Sollas, William Johnson (1911). Ancient hunters: and their modern representatives. Londra: Macmillan ve Co. s.130.

- ^ "On an Earlier and Later Period in the Stone Age". Centilmen Dergisi. May 1862. p. 548.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- ^ Wallace, Alfred Russel (1864). "The Origin of Human Races and the Antiquity of Man Deduced From the Theory of "Natural Selection"". Journal of the Anthropological Society of London. 2.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- ^ Lubbock 1865, s. 481

- ^ Howarth, H.H. (1875). "Report on the Stockholm Meeting of the International Congress of Anthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology". İngiltere ve İrlanda Kraliyet Antropoloji Enstitüsü Dergisi. IV: 347.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- ^ Chambers, William and Robert (20 December 1879). "Pre-historic Records". Chambers Dergisi. 56 (834): 805–808.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- ^ Garašanin, M. (1925). "The Stone Age in the Central Balkan Area". Cambridge Antik Tarih.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- ^ Childe 1951, s. 44

- ^ Childe 1951, s. 34–35

- ^ Childe 1951, s. 14

- ^ Childe 1951, s. 42

- ^ Childe, who was writing for the masses, did not make use of critical apparatus and offered no attributions in his texts. This practice led to the erroneous attribution of the entire three-age system to him. Very little of it originated with him. His synthesis and expansion of its detail is however attributable to his presentations.

- ^ Lubbock 1865, s. 323

- ^ Dawkins, W. Boyd (July 1866). "On the Habits and Conditions of the Two earliest known Races of Men". Quarterly Journal of Science. 3: 344.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- ^ "Kenyon Institute". Alındı 31 Mayıs 2011.

- ^ Howorth, H.H. (1875). "Report of the Stockholm Meeting of the International Congress of Anthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology". Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. London: AIGBI. IV: 354–355.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- ^ Evans 1881, s. 456

- ^ Evans 1881, s. 410

- ^ Evans 1881, s. 474

- ^ Evans 1881, s. 2

- ^ Evans 1881, Bölüm 1

- ^ Pigorini, Luigi; Strobel, Pellegrino (1886). Gaetano Chierici e la paletnologia italiana (italyanca). Parma: Luigi Battei. s. 84.

- ^ Childe, V. Gordon; Patterson, Thomas Carl; Orser, Charles E. (2004). Foundations of social archaeology: selected writings of V. Gordon Childe. Walnut Creek, California: AltaMira Press. s. 173.

- ^ a b c Connah 2010, pp. 62–63

- ^ Kristiansen & Rowlands 1998, s. 47

- ^ Bogucki 2008

- ^ a b Browman & Williams 2002, s. 146

- ^ A predecessor of Lubbock working from the original Danish conception of the three ages.

- ^ Browman & Williams 2002, s. 147

Kaynakça

- Barnes, Harry Elmer (1937). An Intellectual and Cultural History of the Western World, Volume One. Dover Yayınları. OCLC 390382.

- Bogucki, Peter (2008). "Northern and Western Europe: Bronze Age". Encyclopedia of Archaeology. New York: Akademik Basın. pp. 1216–1226.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Browman, David L .; Williams, Steven (2002). Amerikancı Arkeolojinin Kökenleri Üzerine Yeni Perspektifler. Tuscaloosa: Alabama Üniversitesi Yayınları.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Brown, J. Allen (1893). "On the Continuity of the Palaeolithic and Neolithic Periods". Büyük Britanya ve İrlanda Antropoloji Enstitüsü Dergisi. XXII: 66–98.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Childe, V. Gordon (1951). Man Makes Himself (3. baskı). Mentor Books (New American Library of World Literature, Inc.).CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Connah, Graham (2010). Writing About Archaeology. Cambridge University Press.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Dawkins, William Boyd (1880). The Three Pleistocene Strata: Early Man in Britain and his place in the Tertiary Period. London: MacMillan and Co.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Evans, John (1872). The ancient stone implements, weapons and ornaments, of Great Britain. New York: D. Appleton ve Şirketi.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Evans, John (1881). The Ancient Bronze Implements, Weapons, and Ornaments of Great Britain and Ireland. London: Longmans Green & Co.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Goodrum, Matthew R. (2008). "Questioning Thunderstones and Arrowheads: The Problem of Recognizing and Interpreting Stone Artifacts in the Seventeenth Century". Erken Bilim ve Tıp. 13 (5): 482–508. doi:10.1163/157338208X345759.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Gräslund, Bo (1987). The Birth of Prehistoric Chronology. Dating methods and dating systems in nineteenth-century Scandinavian archeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Hamy, M.E.T. (1906). "Matériaux pour servir à l'histoire de l'archéologie préhistorique". Revue Archéologique. 4th Series (in French). 7 (March–April): 239–259.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Heizer, Robert F. (1962). "The background of Thomsen's Three-Age System". Teknoloji ve Kültür. 3 (3): 259–266. doi:10.2307/3100819. JSTOR 3100819.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Kristiansen, Kristian; Rowlands, Michael (1998). Social Transformations in Archaeology: global and local persepectives. Londra: Routledge.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Lubbock, John (1865). Pre-historic times. as illustrated by ancient remains, and the manners and customs of modern savages. Londra ve Edinburgh: Williams ve Norgate.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Malina, Joroslav; Vašíček, Zdenek (1990). Dün ve bugün arkeoloji: Bilimlerde ve beşeri bilimlerde arkeolojinin gelişimi. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Piette, Edouard (1895). "Hiatus et Lacune: Mas-d'Azil'deki geçiş dansının izleri" (PDF). Bulletin de la Société d'anthropologie de Paris (Fransızcada). 6 (6): 235–267. doi:10.3406 / bmsap.1895.5585.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Rowley-Conwy, Peter (2007). Yaratılıştan Tarih Öncesine: Arkeolojik Üç Çağ Sistemi ve Danimarka, İngiltere ve İrlanda'daki Tartışmalı Kabulü. Arkeoloji Tarihinde Oxford Çalışmaları. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Rowley-Conwy, Peter (2006). "Prehistorya Kavramı ve 'Prehistorik' ve 'Prehistorik' Terimlerinin İcadı: İskandinav Kökeni, 1833-1850" (PDF). Avrupa Arkeoloji Dergisi. 9 (1): 103–130. doi:10.1177/1461957107077709.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Stjerna, Knut (1910). "Les groupes de Civilization tr Scandinavie à l'époque des sépultures à galerie". L'Anthropologie (Fransızcada). Paris. XXI: 1–34.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Tetik, Bruce (2006). Arkeolojik düşünce tarihi (2. baskı). Oxford: Cambridge University Press.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)

- Westropp, Hodder M. (1866). "XXII. Erken ve İlkel Irklar Arasındaki Benzer Uygulama Biçimleri Üzerine". Londra Antropoloji Derneği Yayınları. II. Londra: Londra Antropoloji Derneği: 288-294. Alıntı dergisi gerektirir

| günlük =(Yardım)CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı) - Westropp, Hodder M. (1872). Tarih Öncesi Aşamalar; veya Tarih Öncesi Arkeoloji Üzerine Tanıtım Yazıları. Londra: Bell ve Daldy.CS1 bakimi: ref = harv (bağlantı)